Glass theme by KThing

Download: Glass.p3t

(1 background)

Glass is an amorphous (non-crystalline) solid. Because it is often transparent and chemically inert, glass has found widespread practical, technological, and decorative use in window panes, tableware, and optics. Some common objects made of glass like "a glass" of water, "glasses", and "magnifying glass", are named after the material.

Glass is most often formed by rapid cooling (quenching) of the molten form. Some glasses such as volcanic glass are naturally occurring, and Obsidian has been used to make arrowheads and knives since the Stone Age. Archaeological evidence suggests glassmaking dates back to at least 3600 BC in Mesopotamia, Egypt, or Syria. The earliest known glass objects were beads, perhaps created accidentally during metalworking or the production of faience, which is a form of pottery using lead glazes.

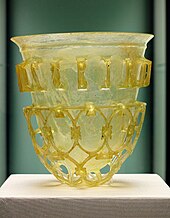

Due to its ease of formability into any shape, glass has been traditionally used for vessels, such as bowls, vases, bottles, jars and drinking glasses. Soda–lime glass, containing around 70% silica, accounts for around 90% of modern manufactured glass. Glass can be coloured by adding metal salts or painted and printed with vitreous enamels, leading to its use in stained glass windows and other glass art objects.

The refractive, reflective and transmission properties of glass make glass suitable for manufacturing optical lenses, prisms, and optoelectronics materials. Extruded glass fibres have applications as optical fibres in communications networks, thermal insulating material when matted as glass wool to trap air, or in glass-fibre reinforced plastic (fibreglass).

Microscopic structure[edit]

The standard definition of a glass (or vitreous solid) is a non-crystalline solid formed by rapid melt quenching.[1][2][3][4] However, the term "glass" is often defined in a broader sense, to describe any non-crystalline (amorphous) solid that exhibits a glass transition when heated towards the liquid state.[4][5]

Glass is an amorphous solid. Although the atomic-scale structure of glass shares characteristics of the structure of a supercooled liquid, glass exhibits all the mechanical properties of a solid.[6][7][8] As in other amorphous solids, the atomic structure of a glass lacks the long-range periodicity observed in crystalline solids. Due to chemical bonding constraints, glasses do possess a high degree of short-range order with respect to local atomic polyhedra.[9] The notion that glass flows to an appreciable extent over extended periods well below the glass transition temperature is not supported by empirical research or theoretical analysis (see viscosity in solids). Though atomic motion at glass surfaces can be observed,[10] and viscosity on the order of 1017–1018 Pa s can be measured in glass, such a high value reinforces the fact that glass would not change shape appreciably over even large periods of time.[5][11]

Formation from a supercooled liquid[edit]

What is the nature of the transition between a fluid or regular solid and a glassy phase? "The deepest and most interesting unsolved problem in solid state theory is probably the theory of the nature of glass and the glass transition." —P.W. Anderson[12]

For melt quenching, if the cooling is sufficiently rapid (relative to the characteristic crystallization time) then crystallization is prevented and instead, the disordered atomic configuration of the supercooled liquid is frozen into the solid state at Tg. The tendency for a material to form a glass while quenched is called glass-forming ability. This ability can be predicted by the rigidity theory.[13] Generally, a glass exists in a structurally metastable state with respect to its crystalline form, although in certain circumstances, for example in atactic polymers, there is no crystalline analogue of the amorphous phase.[14]

Glass is sometimes considered to be a liquid due to its lack of a first-order phase transition[7][15] where certain thermodynamic variables such as volume, entropy and enthalpy are discontinuous through the glass transition range. The glass transition may be described as analogous to a second-order phase transition where the intensive thermodynamic variables such as the thermal expansivity and heat capacity are discontinuous.[2] However, the equilibrium theory of phase transformations does not hold for glass, and hence the glass transition cannot be classed as one of the classical equilibrium phase transformations in solids.[4][5]

Occurrence in nature[edit]

Glass can form naturally from volcanic magma. Obsidian is a common volcanic glass with high silica (SiO2) content formed when felsic lava extruded from a volcano cools rapidly.[16] Impactite is a form of glass formed by the impact of a meteorite, where Moldavite (found in central and eastern Europe), and Libyan desert glass (found in areas in the eastern Sahara, the deserts of eastern Libya and western Egypt) are notable examples.[17] Vitrification of quartz can also occur when lightning strikes sand, forming hollow, branching rootlike structures called fulgurites.[18] Trinitite is a glassy residue formed from the desert floor sand at the Trinity nuclear bomb test site.[19] Edeowie glass, found in South Australia, is proposed to originate from Pleistocene grassland fires, lightning strikes, or hypervelocity impact by one or several asteroids or comets.[20]

-

A piece of volcanic obsidian glass

-

Tube fulgurites

-

Trinitite, a glass made by the Trinity nuclear-weapon test

History[edit]

Naturally occurring obsidian glass was used by Stone Age societies as it fractures along very sharp edges, making it ideal for cutting tools and weapons.[21][22]

Glassmaking dates back at least 6000 years, long before humans had discovered how to smelt iron.[21] Archaeological evidence suggests that the first true synthetic glass was made in Lebanon and the coastal north Syria, Mesopotamia or ancient Egypt.[23][24] The earliest known glass objects, of the mid-third millennium BC, were beads, perhaps initially created as accidental by-products of metalworking (slags) or during the production of faience, a pre-glass vitreous material made by a process similar to glazing.[25]

Early glass was rarely transparent and often contained impurities and imperfections,[21] and is technically faience rather than true glass, which did not appear until the 15th century BC.[26] However, red-orange glass beads excavated from the Indus Valley Civilization dated before 1700 BC (possibly as early as 1900 BC) predate sustained glass production, which appeared around 1600 BC in Mesopotamia and 1500 BC in Egypt.[27][28]

During the Late Bronze Age, there was a rapid growth in glassmaking technology in Egypt and Western Asia.[23] Archaeological finds from this period include coloured glass ingots, vessels, and beads.[23][29]

Much early glass production relied on grinding techniques borrowed from stoneworking, such as grinding and carving glass in a cold state.[30]

The term glass developed in the late Roman Empire. It was in the Roman glassmaking centre at Trier (located in current-day Germany) that the late-Latin term glesum originated, probably from a Germanic word for a transparent, lustrous substance.[31] Glass objects have been recovered across the Roman Empire[32] in domestic, funerary,[33] and industrial contexts,[34] as well as trade items in marketplaces in distant provinces.[35][36] Examples of Roman glass have been found outside of the former Roman Empire in China,[37] the Baltics, the Middle East, and India.[38] The Romans perfected cameo glass, produced by etching and carving through fused layers of different colours to produce a design in relief on the glass object.[39]

In post-classical West Africa, Benin was a manufacturer of glass and glass beads.[40] Glass was used extensively in Europe during the Middle Ages. Anglo-Saxon glass has been found across England during archaeological excavations of both settlement and cemetery sites.[41] From the 10th century onwards, glass was employed in stained glass windows of churches and cathedrals, with famous examples at Chartres Cathedral and the Basilica of Saint-Denis. By the 14th century, architects were designing buildings with walls of stained glass such as Sainte-Chapelle, Paris, (1203–1248) and the East end of Gloucester Cathedral. With the change in architectural style during the Renaissance period in Europe, the use of large stained glass windows became much less prevalent,[42] although stained glass had a major revival with Gothic Revival architecture in the 19th century.[43]

During the 13th century, the island of Murano, Venice, became a centre for glass making, building on medieval techniques to produce colourful ornamental pieces in large quantities.[39] Murano glass makers developed the exceptionally clear colourless glass cristallo, so called for its resemblance to natural crystal, which was extensively used for windows, mirrors, ships' lanterns, and lenses.[21] In the 13th, 14th, and 15th centuries, enamelling and gilding on glass vessels were perfected in Egypt and Syria.[44] Towards the end of the 17th century, Bohemia became an important region for glass production, remaining so until the start of the 20th century. By the 17th century, glass in the Venetian tradition was also being produced in England. In about 1675, George Ravenscroft invented lead crystal glass, with cut glass becoming fashionable in the 18th century.[39] Ornamental glass objects became an important art medium during the Art Nouveau period in the late 19th century.[39]

Throughout the 20th century, new mass production techniques led to the widespread availability of glass in much larger amounts, making it practical as a building material and enabling new applications of glass.[45] In the 1920s a mould-etch process was developed, in which art was etched directly into the mould so that each cast piece emerged from the mould with the image already on the surface of the glass. This reduced manufacturing costs and, combined with a wider use of coloured glass, led to cheap glassware in the 1930s, which later became known as Depression glass.[46] In the 1950s, Pilkington Bros., England, developed the float glass process, producing high-quality distortion-free flat sheets of glass by floating on molten tin.[21] Modern multi-story buildings are frequently constructed with curtain walls made almost entirely of glass.[47] Laminated glass has been widely applied to vehicles for windscreens.[48] Optical glass for spectacles has been used since the Middle Ages.[49] The production of lenses has become increasingly proficient, aiding astronomers[50] as well as having other applications in medicine and science.[51] Glass is also employed as the aperture cover in many solar energy collectors.[52]

In the 21st century, glass manufacturers have developed different brands of chemically strengthened glass for widespread application in touchscreens for smartphones, tablet computers, and many other types of information appliances. These include Gorilla Glass, developed and manufactured by Corning, AGC Inc.'s Dragontrail and Schott AG's Xensation.[53][54][55]

Physical properties[edit]

Optical[edit]

Glass is in widespread use in optical systems due to its ability to refract, reflect, and transmit light following geometrical optics. The most common and oldest applications of glass in optics are as lenses, windows, mirrors, and prisms.[56] The key optical properties refractive index, dispersion, and transmission, of glass are strongly dependent on chemical composition and, to a lesser degree, its thermal history.[56] Optical glass typically has a refractive index of 1.4 to 2.4, and an Abbe number (which characterises dispersion) of 15 to 100.[56] The refractive index may be modified by high-density (refractive index increases) or low-density (refractive index decreases) additives.[57]

Glass transparency results from the absence of grain boundaries which diffusely scatter light in polycrystalline materials.[58] Semi-opacity due to crystallization may be induced in many glasses by maintaining them for a long period at a temperature just insufficient to cause fusion. In this way, the crystalline, devitrified material, known as Réaumur's glass porcelain is produced.[44][59] Although generally transparent to visible light, glasses may be opaque to other wavelengths of light. While silicate glasses are generally opaque to infrared wavelengths with a transmission cut-off at 4 μm, heavy-metal fluoride and chalcogenide glasses are transparent to infrared wavelengths of 7 to 18 μm.[60] The addition of metallic oxides results in different coloured glasses as the metallic ions will absorb wavelengths of light corresponding to specific colours.[60]

Other[edit]

In the manufacturing process, glasses can be poured, formed, extruded and moulded into forms ranging from flat sheets to highly intricate shapes.[61] The finished product is brittle but can be laminated or tempered to enhance durability.[62][63] Glass is typically inert, resistant to chemical attack, and can mostly withstand the action of water, making it an ideal material for the manufacture of containers for foodstuffs and most chemicals.[21][64][65] Nevertheless, although usually highly resistant to chemical attack, glass will corrode or dissolve under some conditions.[64][66] The materials that make up a particular glass composition affect how quickly the glass corrodes. Glasses containing a high proportion of alkali or alkaline earth elements are more susceptible to corrosion than other glass compositions.[67][68]

The density of glass varies with chemical composition with values ranging from 2.2 grams per cubic centimetre (2,200 kg/m3) for fused silica to 7.2 grams per cubic centimetre (7,200 kg/m3) for dense flint glass.[69] Glass is stronger than most metals, with a theoretical tensile strength for pure, flawless glass estimated at 14 to 35 gigapascals (2,000,000 to 5,100,000 psi) due to its ability to undergo reversible compression without fracture. However, the presence of scratches, bubbles, and other microscopic flaws lead to a typical range of 14 to 175 megapascals (2,000 to 25,400 psi) in most commercial glasses.[60] Several processes such as toughening can increase the strength of glass.[70] Carefully drawn flawless glass fibres can be produced with a strength of up to 11.5 gigapascals (1,670,000 psi).[60]

Reputed flow[edit]

The observation that old windows are sometimes found to be thicker at the bottom than at the top is often offered as supporting evidence for the view that glass flows over a timescale of centuries, the assumption being that the glass has exhibited the liquid property of flowing from one shape to another.[71] This assumption is incorrect, as once solidified, glass stops flowing. The sags and ripples observed in old glass were already there the day it was made; manufacturing processes used in the past produced sheets with imperfect surfaces and non-uniform thickness (the near-perfect float glass used today only became widespread in the 1960s).[7]

A 2017 study computed the rate of flow of the medieval glass used in Westminster Abbey from the year 1268. The study found that the room temperature viscosity of this glass was roughly 1024 Pa·s which is about 1016 times less viscous than a previous estimate made in 1998, which focused on soda-lime silicate glass. Even with this lower viscosity, the study authors calculated that the maximum flow rate of medieval glass is 1 nm per billion years, making it impossible to observe in a human timescale.[72][73]

Types[edit]

Silicate glasses[edit]

A nice glass theme to go with your piece of ‘niceness’ known as the PS3.