Neuron theme by opy01

Download: Neuron.p3t

(1 background)

| Neuron | |

|---|---|

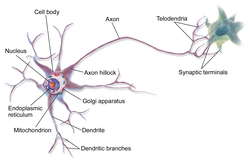

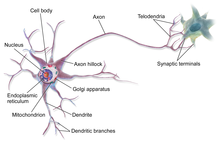

Anatomy of a multipolar neuron | |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D009474 |

| NeuroLex ID | sao1417703748 |

| TA98 | A14.0.00.002 |

| TH | H2.00.06.1.00002 |

| FMA | 54527 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

Within a nervous system, a neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network. Neurons communicate with other cells via synapses, which are specialized connections that commonly use minute amounts of chemical neurotransmitters to pass the electric signal from the presynaptic neuron to the target cell through the synaptic gap.

Neurons are the main components of nervous tissue in all animals except sponges and Placozoa. Non-animals like plants and fungi do not have nerve cells. Molecular evidence suggests that the ability to generate electric signals first appeared in evolution some 700 to 800 million years ago, during the Tonian period. Predecessors of neurons were the peptidergic secretory cells. They eventually gained new gene modules which enabled cells to create post-synaptic scaffolds and ion channels that generate fast electrical signals. The ability to generate electric signals was a key innovation in the evolution of the nervous system.[1]

Neurons are typically classified into three types based on their function. Sensory neurons respond to stimuli such as touch, sound, or light that affect the cells of the sensory organs, and they send signals to the spinal cord or brain. Motor neurons receive signals from the brain and spinal cord to control everything from muscle contractions[2] to glandular output. Interneurons connect neurons to other neurons within the same region of the brain or spinal cord. When multiple neurons are functionally connected together, they form what is called a neural circuit.

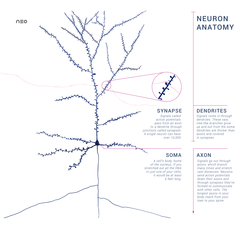

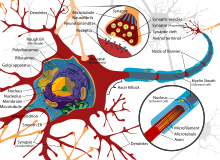

Neurons are special cells which are made up of some structures that are common to all other eukaryotic cells such as the cell body (soma), a nucleus, smooth and rough endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, and other cellular components.[3] Additionally, neurons have other unique structures such as dendrites, and a single axon.[3] The soma is a compact structure, and the axon and dendrites are filaments extruding from the soma. Dendrites typically branch profusely and extend a few hundred micrometers from the soma. The axon leaves the soma at a swelling called the axon hillock and travels for as far as 1 meter in humans or more in other species. It branches but usually maintains a constant diameter. At the farthest tip of the axon's branches are axon terminals, where the neuron can transmit a signal across the synapse to another cell. Neurons may lack dendrites or have no axon. The term neurite is used to describe either a dendrite or an axon, particularly when the cell is undifferentiated.

Most neurons receive signals via the dendrites and soma and send out signals down the axon. At the majority of synapses, signals cross from the axon of one neuron to a dendrite of another. However, synapses can connect an axon to another axon or a dendrite to another dendrite. The signaling process is partly electrical and partly chemical. Neurons are electrically excitable, due to maintenance of voltage gradients across their membranes. If the voltage changes by a large enough amount over a short interval, the neuron generates an all-or-nothing electrochemical pulse called an action potential. This potential travels rapidly along the axon and activates synaptic connections as it reaches them. Synaptic signals may be excitatory or inhibitory, increasing or reducing the net voltage that reaches the soma.

In most cases, neurons are generated by neural stem cells during brain development and childhood. Neurogenesis largely ceases during adulthood in most areas of the brain.

Nervous system[edit]

Neurons are the primary components of the nervous system, along with the glial cells that give them structural and metabolic support.[4] The nervous system is made up of the central nervous system, which includes the brain and spinal cord, and the peripheral nervous system, which includes the autonomic, enteric and somatic nervous systems.[5] In vertebrates, the majority of neurons belong to the central nervous system, but some reside in peripheral ganglia, and many sensory neurons are situated in sensory organs such as the retina and cochlea.

Axons may bundle into fascicles that make up the nerves in the peripheral nervous system (like strands of wire make up cables). Bundles of axons in the central nervous system are called tracts.

Anatomy and histology[edit]

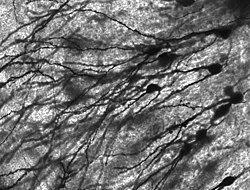

Neurons are highly specialized for the processing and transmission of cellular signals. Given their diversity of functions performed in different parts of the nervous system, there is a wide variety in their shape, size, and electrochemical properties. For instance, the soma of a neuron can vary from 4 to 100 micrometers in diameter.[6]

- The soma is the body of the neuron. As it contains the nucleus, most protein synthesis occurs here. The nucleus can range from 3 to 18 micrometers in diameter.[7]

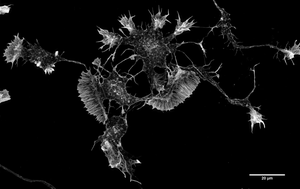

- The dendrites of a neuron are cellular extensions with many branches. This overall shape and structure are referred to metaphorically as a dendritic tree. This is where the majority of input to the neuron occurs via the dendritic spine.

- The axon is a finer, cable-like projection that can extend tens, hundreds, or even tens of thousands of times the diameter of the soma in length. The axon primarily carries nerve signals away from the soma and carries some types of information back to it. Many neurons have only one axon, but this axon may—and usually will—undergo extensive branching, enabling communication with many target cells. The part of the axon where it emerges from the soma is called the axon hillock. Besides being an anatomical structure, the axon hillock also has the greatest density of voltage-dependent sodium channels. This makes it the most easily excited part of the neuron and the spike initiation zone for the axon. In electrophysiological terms, it has the most negative threshold potential.

- While the axon and axon hillock are generally involved in information outflow, this region can also receive input from other neurons.

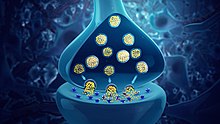

- The axon terminal is found at the end of the axon farthest from the soma and contains synapses. Synaptic boutons are specialized structures where neurotransmitter chemicals are released to communicate with target neurons. In addition to synaptic boutons at the axon terminal, a neuron may have en passant boutons, which are located along the length of the axon.

The accepted view of the neuron attributes dedicated functions to its various anatomical components; however, dendrites and axons often act in ways contrary to their so-called main function.[8]

Axons and dendrites in the central nervous system are typically only about one micrometer thick, while some in the peripheral nervous system are much thicker. The soma is usually about 10–25 micrometers in diameter and often is not much larger than the cell nucleus it contains. The longest axon of a human motor neuron can be over a meter long, reaching from the base of the spine to the toes.

Sensory neurons can have axons that run from the toes to the posterior column of the spinal cord, over 1.5 meters in adults. Giraffes have single axons several meters in length running along the entire length of their necks. Much of what is known about axonal function comes from studying the squid giant axon, an ideal experimental preparation because of its relatively immense size (0.5–1 millimeter thick, several centimeters long).

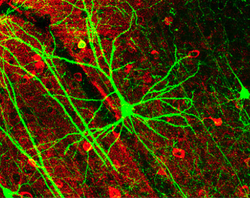

Fully differentiated neurons are permanently postmitotic[9] however, stem cells present in the adult brain may regenerate functional neurons throughout the life of an organism (see neurogenesis). Astrocytes are star-shaped glial cells. They have been observed to turn into neurons by virtue of their stem cell-like characteristic of pluripotency.

Membrane[edit]

Like all animal cells, the cell body of every neuron is enclosed by a plasma membrane, a bilayer of lipid molecules with many types of protein structures embedded in it.[10] A lipid bilayer is a powerful electrical insulator, but in neurons, many of the protein structures embedded in the membrane are electrically active. These include ion channels that permit electrically charged ions to flow across the membrane and ion pumps that chemically transport ions from one side of the membrane to the other. Most ion channels are permeable only to specific types of ions. Some ion channels are voltage gated, meaning that they can be switched between open and closed states by altering the voltage difference across the membrane. Others are chemically gated, meaning that they can be switched between open and closed states by interactions with chemicals that diffuse through the extracellular fluid. The ion materials include sodium, potassium, chloride, and calcium. The interactions between ion channels and ion pumps produce a voltage difference across the membrane, typically a bit less than 1/10 of a volt at baseline. This voltage has two functions: first, it provides a power source for an assortment of voltage-dependent protein machinery that is embedded in the membrane; second, it provides a basis for electrical signal transmission between different parts of the membrane.

Histology and internal structure[edit]

Numerous microscopic clumps called Nissl bodies (or Nissl substance) are seen when nerve cell bodies are stained with a basophilic ("base-loving") dye. These structures consist of rough endoplasmic reticulum and associated ribosomal RNA. Named after German psychiatrist and neuropathologist Franz Nissl (1860–1919), they are involved in protein synthesis and their prominence can be explained by the fact that nerve cells are very metabolically active. Basophilic dyes such as aniline or (weakly) haematoxylin[11] highlight negatively charged components, and so bind to the phosphate backbone of the ribosomal RNA.

The cell body of a neuron is supported by a complex mesh of structural proteins called neurofilaments, which together with neurotubules (neuronal microtubules) are assembled into larger neurofibrils.[12] Some neurons also contain pigment granules, such as neuromelanin (a brownish-black pigment that is byproduct of synthesis of catecholamines), and lipofuscin (a yellowish-brown pigment), both of which accumulate with age.[13][14][15] Other structural proteins that are important for neuronal function are actin and the tubulin of microtubules. Class III β-tubulin is found almost exclusively in neurons. Actin is predominately found at the tips of axons and dendrites during neuronal development. There the actin dynamics can be modulated via an interplay with microtubule.[16]

There are different internal structural characteristics between axons and dendrites. Typical axons almost never contain ribosomes, except some in the initial segment. Dendrites contain granular endoplasmic reticulum or ribosomes, in diminishing amounts as the distance from the cell body increases.

Classification[edit]

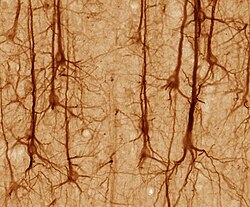

Neurons vary in shape and size and can be classified by their morphology and function.[18] The anatomist Camillo Golgi grouped neurons into two types; type I with long axons used to move signals over long distances and type II with short axons, which can often be confused with dendrites. Type I cells can be further classified by the location of the soma. The basic morphology of type I neurons, represented by spinal motor neurons, consists of a cell body called the soma and a long thin axon covered by a myelin sheath. The dendritic tree wraps around the cell body and receives signals from other neurons. The end of the axon has branching axon terminals that release neurotransmitters into a gap called the synaptic cleft between the terminals and the dendrites of the next neuron.[citation needed]

Structural classification[edit]

Polarity[edit]

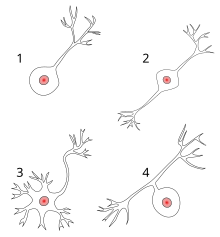

1 Unipolar neuron

2 Bipolar neuron

3 Multipolar neuron

4 Pseudounipolar neuron

Most neurons can be anatomically characterized as:[19]

- Unipolar: single process. Unipolar cells are exclusively sensory neurons. Their dendrites are receiving sensory information, sometimes directly from the stimulus itself. The cell bodies of unipolar neurons are always found in ganglia. Sensory reception is a peripheral function, so the cell body is in the periphery, though closer to the CNS in a ganglion. The axon projects from the dendrite endings, past the cell body in a ganglion, and into the central nervous system.

- Bipolar: 1 axon and 1 dendrite. They are found mainly in the olfactory epithelium, and as part of the retina.

- Multipolar: 1 axon and 2 or more dendrites

- Anaxonic: where the axon cannot be distinguished from the dendrite(s)

- Pseudounipolar: 1 process which then serves as both an axon and a dendrite

Other[edit]

Some unique neuronal types can be identified according to their location in the nervous system and distinct shape. Some examples are:[citation needed]

- Basket cells, interneurons that form a dense plexus of terminals around the soma of target cells, found in the cortex and cerebellum

- Betz cells, large motor neurons

- Lugaro cells, interneurons of the cerebellum

- Medium spiny neurons, most neurons in the corpus striatum

- Purkinje cells, huge neurons in the cerebellum, a type of Golgi I multipolar neuron

- Pyramidal cells, neurons with triangular soma, a type of Golgi I

- Rosehip cells, unique human inhibitory neurons that interconnect with Pyramidal cells

- Renshaw cells, neurons with both ends linked to alpha motor neurons

- Unipolar brush cells, interneurons with unique dendrite ending in a brush-like tuft

- Granule cells, a type of Golgi II neuron

- Anterior horn cells, motoneurons located in the spinal cord

- Spindle cells, interneurons that connect widely separated areas of the brain

Functional classification[edit]

Direction[edit]

- Afferent neurons convey information from tissues and organs into the central nervous system and are also called sensory neurons.

- Efferent neurons (motor neurons) transmit signals from the central nervous system to the effector cells.

- Interneurons connect neurons within specific regions of the central nervous system.

Afferent and efferent also refer generally to neurons that, respectively, bring information to or send information from the brain.

Action on other neurons[edit]

A neuron affects other neurons by releasing a neurotransmitter that binds to chemical receptors. The effect upon the postsynaptic neuron is determined by the type of receptor that is activated, not by the presynaptic neuron or by the neurotransmitter. A neurotransmitter can be thought of as a key, and a receptor as a lock: the same neurotransmitter can activate multiple types of receptors. Receptors can be classified broadly as excitatory (causing an increase in firing rate), inhibitory (causing a decrease in firing rate), or modulatory (causing long-lasting effects not directly related to firing rate).[citation needed]

The two most common (90%+) neurotransmitters in the brain, glutamate and GABA, have largely consistent actions. Glutamate acts on several types of receptors, and has effects that are excitatory at ionotropic receptors and a modulatory effect at metabotropic receptors. Similarly, GABA acts on several types of receptors, but all of them have inhibitory effects (in adult animals, at least). Because of this consistency, it is common for neuroscientists to refer to cells that release glutamate as "excitatory neurons", and cells that release GABA as "inhibitory neurons". Some other types of neurons have consistent effects, for example, "excitatory" motor neurons in the spinal cord that release acetylcholine, and "inhibitory" spinal neurons that release glycine.[citation needed]

The distinction between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters is not absolute. Rather, it depends on the class of chemical receptors present on the postsynaptic neuron. In principle, a single neuron, releasing a single neurotransmitter, can have excitatory effects on some targets, inhibitory effects on others, and modulatory effects on others still. For example, photoreceptor cells in the retina constantly release the neurotransmitter glutamate in the absence of light. So-called OFF bipolar cells are, like most neurons, excited by the released glutamate. However, neighboring target neurons called ON bipolar cells are instead inhibited by glutamate, because they lack typical ionotropic glutamate receptors and instead express a class of inhibitory metabotropic glutamate receptors.[20] When light is present, the photoreceptors cease releasing glutamate, which relieves the ON bipolar cells from inhibition, activating them; this simultaneously removes the excitation from the OFF bipolar cells, silencing them.[citation needed]

It is possible to identify the type of inhibitory effect a presynaptic neuron will have on a postsynaptic neuron, based on the proteins the presynaptic neuron expresses. Parvalbumin-expressing neurons typically dampen the output signal of the postsynaptic neuron in the visual cortex, whereas somatostatin-expressing neurons typically block dendritic inputs to the postsynaptic neuron.[21]

Discharge patterns[edit]

Neurons have intrinsic electroresponsive properties like intrinsic transmembrane voltage oscillatory patterns.[22] So neurons can be classified according to their electrophysiological characteristics:

- Tonic or regular spiking. Some neurons are typically constantly (tonically) active, typically firing at a constant frequency. Example: interneurons in neurostriatum.

- Phasic or bursting. Neurons that fire in bursts are called phasic.

- Fast-spiking. Some neurons are notable for their high firing rates, for example some types of cortical inhibitory interneurons, cells in globus pallidus, retinal ganglion cells.[23][24]

Neurotransmitter[edit]

Neurotransmitters are chemical messengers passed from one neuron to another neuron or to a muscle cell or gland cell.

- Cholinergic neurons – acetylcholine. Acetylcholine is released from presynaptic neurons into the synaptic cleft. It acts as a ligand for both ligand-gated ion channels and metabotropic (GPCRs) muscarinic receptors. Nicotinic receptors are pentameric ligand-gated ion channels composed of alpha and beta subunits that bind nicotine. Ligand binding opens the channel causing influx of Na+ depolarization and increases the probability of presynaptic neurotransmitter release. Acetylcholine is synthesized from choline and acetyl coenzyme A.

- Adrenergic neurons – noradrenaline. Noradrenaline (norepinephrine) is released from most postganglionic neurons in the sympathetic nervous system onto two sets of GPCRs: alpha adrenoceptors and beta adrenoceptors. Noradrenaline is one of the three common catecholamine neurotransmitter, and the most prevalent of them in the peripheral nervous system; as with other catecholamines, it is synthesised from tyrosine.

- GABAergic neurons – gamma aminobutyric acid. GABA is one of two neuroinhibitors in the central nervous system (CNS), along with glycine. GABA has a homologous function to ACh, gating anion channels that allow Cl− ions to enter the post synaptic neuron. Cl− causes hyperpolarization within the neuron, decreasing the probability of an action potential firing as the voltage becomes more negative (for an action potential to fire, a positive voltage threshold must be reached). GABA is synthesized from