Pixar theme by Ali4Chris

Download: Pixar.p3t

(7 backgrounds)

Logo used since 1995 | |

Headquarters in Emeryville, California | |

| Company type | Subsidiary |

|---|---|

| Industry | Animation |

| Predecessor | The Graphics Group of Lucasfilm Computer Division (1979–1986) |

| Founded | February 3, 1986 in Richmond, California |

| Founders | |

| Headquarters | 1200 Park Avenue, , U.S. |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Products | Computer animations |

| Brands | |

Number of employees | 1,233 (2020) |

| Parent | Walt Disney Studios (2006–present) |

| Website | www |

| Footnotes / references [1][2][3] | |

Pixar Animation Studios, known simply as Pixar (/ˈpɪksɑːr/), is an American animation studio based in Emeryville, California, known for its critically and commercially successful computer-animated feature films. Since 2006, Pixar has been a subsidiary of Walt Disney Studios, a division of Disney Entertainment, a segment of the Walt Disney Company.

Pixar started in 1979 as part of the Lucasfilm computer division. It was known as the Graphics Group before its spin-off as a corporation in 1986, with funding from Apple co-founder Steve Jobs who became its majority shareholder.[2] Disney announced its acquisition of Pixar in January 2006, and completed it in May 2006.[4][5][6] Pixar is best known for its feature films, technologically powered by RenderMan, the company's own implementation of the industry-standard RenderMan Interface Specification image-rendering API. The studio's mascot is Luxo Jr., a desk lamp from the studio's 1986 short film of the same name.

Pixar has produced 28 feature films, starting with Toy Story (1995), which is the first fully computer-animated feature film; its most recent film was Inside Out 2 (2024). The studio has also produced many short films. As of July 2023[update], its feature films have earned over $15 billion at the worldwide box office with an average gross of $546.9 million per film.[7] Toy Story 3 (2010), Finding Dory (2016), Incredibles 2 (2018), Toy Story 4 (2019) and Inside Out 2 (2024) all grossed over $1 billion and are among the 50 highest-grossing films of all time. Moreover, 15 of Pixar's films are in the 50 highest-grossing animated films of all time.

Pixar has earned 23 Academy Awards, 10 Golden Globe Awards, and 11 Grammy Awards, along with numerous other awards and acknowledgments. Since its inauguration in 2001, eleven Pixar films have won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature, including Finding Nemo (2003), The Incredibles (2004), Ratatouille (2007), WALL-E (2008), Up (2009), the aforementioned Toy Story 3 and Toy Story 4, Brave (2012), Inside Out (2015), Coco (2017), and Soul (2020). Toy Story 3 and Up were also nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture.

In February 2009, Pixar executives John Lasseter, Brad Bird, Pete Docter, Andrew Stanton, and Lee Unkrich were presented with the Golden Lion award for Lifetime Achievement by the Venice Film Festival. The physical award was ceremoniously handed to Lucasfilm's founder, George Lucas.

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

Pixar got its start in 1974, when New York Institute of Technology's (NYIT) founder, Alexander Schure, who was also the owner of a traditional animation studio, established the Computer Graphics Lab (CGL) and recruited computer scientists who shared his ambitions about creating the world's first computer-animated film. Edwin Catmull and Malcolm Blanchard were the first to be hired and were soon joined by Alvy Ray Smith and David DiFrancesco some months later, which were the four original members of the Computer Graphics Lab, located in a converted two-story garage acquired from the former Vanderbilt-Whitney estate.[8][9] Schure invested significant funds into the computer graphics lab, approximately $15 million, providing the resources the group needed but contributing to NYIT's financial difficulties.[10] Eventually, the group realized they needed to work in a real film studio to reach their goal. Francis Ford Coppola then invited Smith to his house for a three-day media conference, where Coppola and George Lucas shared their visions for the future of digital moviemaking.[11]

When Lucas approached them and offered them a job at his studio, six employees moved to Lucasfilm. During the following months, they gradually resigned from CGL, found temporary jobs for about a year to avoid making Schure suspicious, and joined the Graphics Group at Lucasfilm.[12][13] The Graphics Group, which was one-third of the Computer Division of Lucasfilm, was launched in 1979 with the hiring of Catmull from NYIT,[14] where he was in charge of the Computer Graphics Lab. He was then reunited with Smith, who also made the journey from NYIT to Lucasfilm, and was made the director of the Graphics Group. At NYIT, the researchers pioneered many of the CG foundation techniques — in particular, the invention of the alpha channel by Catmull and Smith.[15] Over the next several years, the CGL would produce a few frames of an experimental film called The Works. After moving to Lucasfilm, the team worked on creating the precursor to RenderMan, called REYES (for "renders everything you ever saw"), and developed several critical technologies for CG — including particle effects and various animation tools.[16]

John Lasseter was hired to the Lucasfilm team for a week in late 1983 with the title "interface designer"; he animated the short film The Adventures of André & Wally B.[17] In the next few years, a designer suggested naming a new digital compositing computer the "Picture Maker". Smith suggested that the laser-based device have a catchier name, and came up with "Pixer", which after a meeting was changed to "Pixar".[18] According to Michael Rubin, the author of Droidmaker: George Lucas and the Digital Revolution, Smith and three other employees came up with the name during a restaurant visit in 1981, but when interviewing them he got four different versions about the origin of the name.[19]

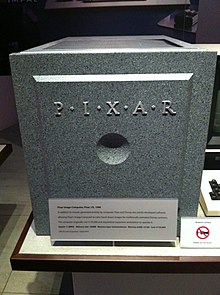

In 1982, the Pixar team began working on special-effects film sequences with Industrial Light & Magic. After years of research, and key milestones such as the Genesis Effect in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan and the Stained Glass Knight in Young Sherlock Holmes,[14] the group, which then numbered 40 individuals, was spun out as a corporation in February 1986 by Catmull and Smith. Among the 38 remaining employees were Malcolm Blanchard, David DiFrancesco, Ralph Guggenheim, and Bill Reeves, who had been part of the team since the days of NYIT. Tom Duff, also an NYIT member, would later join Pixar after its formation.[2] With Lucas's 1983 divorce, which coincided with the sudden dropoff in revenues from Star Wars licenses following the release of Return of the Jedi, they knew he would most likely sell the whole Graphics Group. Worried that the employees would be lost to them if that happened, which would prevent the creation of the first computer-animated movie, they concluded that the best way to keep the team together was to turn the group into an independent company. But Moore's Law also suggested that sufficient computing power for the first film was still some years away, and they needed to focus on a proper product until then. Eventually, they decided they should be a hardware company in the meantime, with their Pixar Image Computer as the core product, a system primarily sold to governmental, scientific, and medical markets.[2][10][20] They also used SGI computers.[21]

In 1983, Nolan Bushnell founded a new computer-guided animation studio called Kadabrascope as a subsidiary of his Chuck E. Cheese's Pizza Time Theatres company (PTT), which was founded in 1977. Only one major project was made out of the new studio, an animated Christmas special for NBC starring Chuck E. Cheese and other PTT mascots; known as "Chuck E. Cheese: The Christmas That Almost Wasn't". The animation movement would be made using tweening instead of traditional cel animation. After the video game crash of 1983, Bushnell started selling some subsidiaries of PTT to keep the business afloat. Sente Technologies (another division, was founded to have games distributed in PTT stores) was sold to Bally Games and Kadabrascope was sold to Lucasfilm. The Kadabrascope assets were combined with the Computer Division of Lucasfilm.[22] Coincidentally, one of Steve Jobs's first jobs was under Bushnell in 1973 as a technician at his other company Atari, which Bushnell sold to Warner Communications in 1976 to focus on PTT.[23] PTT would later go bankrupt in 1984 and be acquired by ShowBiz Pizza Place.[24]

Independent company (1986–1999)[edit]

In 1986, the newly independent Pixar was headed by President Edwin Catmull and Executive Vice President Alvy Ray Smith. Lucas's search for investors led to an offer from Steve Jobs, which Lucas initially found too low. He eventually accepted after determining it impossible to find other investors. At that point, Smith and Catmull had been declined by 35 venture capitalists and ten large corporations,[25] including a deal with General Motors which fell through three days before signing the contracts.[26] Jobs, who had been edged out of Apple in 1985,[2] was now founder and CEO of the new computer company NeXT. On February 3, 1986, he paid $5 million of his own money to George Lucas for technology rights and invested $5 million cash as capital into the company, joining the board of directors as chairman.[2][27]

In 1985 while still at Lucasfilm, they had made a deal with the Japanese publisher Shogakukan to make a computer-animated movie called Monkey, based on the Monkey King. The project continued sometime after they became a separate company in 1986, but it became clear that the technology was not sufficiently advanced. The computers were not powerful enough and the budget would be too high. As a result they focused on the computer hardware business for years until a computer-animated feature became feasible according to Moore's law.[28][29]

At the time, Walt Disney Studios made the decision to develop more efficient ways of producing animation. They reached out to Graphics Group at Lucasfilm and to Digital Productions. Because of the Graphics Group's deeper understanding of animation, and Smith's experience with paint programs at NYIT, it convinced Disney they were the right choice. In May 1986 Pixar signed a contract with Disney, who eventually bought and used the Pixar Image Computer and custom software written by Pixar as part of its Computer Animation Production System (CAPS) project, to migrate the laborious ink and paint part of the 2D animation process to a more automated method.[30] The company's first feature film to be released using this new animation method was The Rescuers Down Under (1990).[31][32]

In a bid to drive sales of the system and increase the company's capital, Jobs suggested releasing the product to the mainstream market. Pixar employee John Lasseter, who had long been working on not-for-profit short demonstration animations, such as Luxo Jr. (1986) to show off the device's capabilities, premiered his creations to great fanfare at SIGGRAPH, the computer graphics industry's largest convention.[33]

However, the Image Computer had inadequate sales[33] which threatened to end the company as financial losses grew. Jobs increased investment in exchange for an increased stake, reducing the proportion of management and employee ownership until eventually, his total investment of $50 million gave him control of the entire company. In 1989, Lasseter's growing animation department which was originally composed of just four people (Lasseter, Bill Reeves, Eben Ostby, and Sam Leffler), was turned into a division that produced computer-animated commercials for outside companies.[1][34][35] In April 1990, Pixar sold its hardware division, including all proprietary hardware technology and imaging software, to Vicom Systems, and transferred 18 of Pixar's approximately 100 employees. In the same year Pixar moved from San Rafael to Richmond, California.[36] Pixar released some of its software tools on the open market for Macintosh and Windows systems. RenderMan is one of the leading 3D packages of the early 1990s, and Typestry is a special-purpose 3D text renderer that competed with RayDream.[citation needed]

During this period of time, Pixar continued its successful relationship with Walt Disney Feature Animation, a studio whose corporate parent would ultimately become its most important partner. As 1991 began, however the layoff of 30 employees in the company's computer hardware department—including the company's president, Chuck Kolstad,[37] reduced the total number of employees to just 42, approximately its original number.[38] On March 6, 1991, Steve Jobs bought the company from its employees and became the full owner. He contemplated folding it into NeXT, but the NeXT's co-founders refused.[26] A few months later Pixar made a historic $26 million deal with Disney to produce three computer-animated feature films, the first of which was Toy Story (1995), the product of the technological limitations that challenged CGI.[39] By then the software programmers, who were doing RenderMan and IceMan, and Lasseter's animation department, which made television commercials (and four Luxo Jr. shorts for Sesame Street the same year), were all that remained of Pixar.[40]

Despite the income from these projects, the company still continued to lose money and Steve Jobs, as chairman of the board and now owner, often considered selling it. As late as 1994, Jobs contemplated selling Pixar to other companies such as Hallmark Cards, Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, and Oracle CEO and co-founder Larry Ellison.[41] After learning from New York critics that Toy Story would probably be a hit, and confirming that Disney would distribute it for the 1995 Christmas season, he decided to give Pixar another chance.[42][43] Also for the first time, he took an active leadership role in the company and made himself CEO.[44] Toy Story grossed more than $373 million worldwide[45] and, when Pixar held its initial public offering on November 29, 1995, it exceeded Netscape's as the biggest IPO of the year. In its first half-hour of trading, Pixar stock shot from $22 to $45, delaying trading because of unmatched buy orders. Shares climbed to US$49 and closed the day at $39.[46]

The company continued to make the television commercials during the production of Toy Story, which came to an end on July 9, 1996, when Pixar announced they would shut down its television commercial unit, which counted 18 employees, to focus on longer projects and interactive entertainment.[47][48]

During the 1990s and 2000s, Pixar gradually developed the "Pixar Braintrust", the studio's primary creative development process, in which all of its directors, writers, and lead storyboard artists regularly examine each other's projects and give very candid "notes", the industry term for constructive criticism.[49] The Braintrust operates under a philosophy of a "filmmaker-driven studio", in which creatives help each other move their films forward through a process somewhat like peer review, as opposed to the traditional Hollywood approach of an "executive-driven studio" in which directors are micromanaged through "mandatory notes" from development executives outranking the producers.[50][51] According to Catmull, it evolved out of the working relationship between Lasseter, Andrew Stanton, Pete Docter, Lee Unkrich, and Joe Ranft on Toy Story.[49]

As a result of the success of Toy Story, Pixar built a new studio at the Emeryville campus which was designed by PWP Landscape Architecture and opened in November 2000.[citation needed]

Collaboration with Disney (1999–2006)[edit]

Pixar and Disney had disagreements over the production of Toy Story 2. Originally intended as a direct-to-video release (and thus not part of Pixar's three-picture deal), the film was eventually upgraded to a theatrical release during production. Pixar demanded that the film then be counted toward the three-picture agreement, but Disney refused.[52] Though profitable for both, Pixar later complained that the arrangement was not equitable. Pixar was responsible for creation and production, while Disney handled marketing and distribution. Profits and production costs were split equally, but Disney exclusively owned all story, character, and sequel rights and also collected a 10- to 15-percent distribution fee.[53]

The two companies attempted to reach a new agreement for ten months and failed on January 26, 2001, July 26, 2002, April 22, 2003, January 16, 2004, July 22, 2004, and January 14, 2005. The proposed distribution deal meant Pixar would control production and own the resulting story, character, and sequel rights, while Disney would own the right of first refusal to distribute any sequels. Pixar also wanted to finance its own films and collect 100 percent profit, paying Disney the 10- to 15-percent distribution fee.[54] In addition, as part of any distribution agreement with Disney, Pixar demanded control over films already in production under the old agreement, including The Incredibles (2004) and Cars (2006). Disney considered these conditions unacceptable, but Pixar would not concede.

Disagreements between Steve Jobs and Disney chairman and CEO Michael Eisner caused the negotiations to cease in 2004, with Disney forming Circle Seven Animation and Jobs declaring that Pixar was actively seeking partners other than Disney.[55] Despite this announcement and several talks with Warner Bros., Sony Pictures, and 20th Century Fox, Pixar did not enter negotiations with other distributors,[56] although a Warner Bros. spokesperson told CNN, "We would love to be in business with Pixar. They are a great company."[54] After a lengthy hiatus, negotiations between the two companies resumed following the departure of Eisner from Disney in September 2005. In preparation for potential fallout between Pixar and Disney, Jobs announced in late 2004 that Pixar would no longer release movies at the Disney-dictated November time frame, but during the more lucrative early summer months. This would also allow Pixar to release DVDs for its major releases during the Christmas shopping season. An added benefit of delaying Cars from November 4, 2005, to June 9, 2006, was to extend the time frame remaining on the Pixar-Disney contract, to see how things would play out between the two companies.[56]

Pending the Disney acquisition of Pixar, the two companies created a distribution deal for the intended 2007 release of Ratatouille, to ensure that if the acquisition failed, this one film would be released through Disney's distribution channels. In contrast to the earlier Pixar deal, Ratatouille was meant to remain a Pixar property and Disney would have received a distribution fee. The completion of Disney's Pixar acquisition, however, nullified this distribution arrangement.[57]

Walt Disney Studios subsidiary (2006–present)[edit]

After extended negotiations, Disney ultimately agreed on January 24, 2006, to buy Pixar for approximately $7.4 billion in an all-stock deal.[58] Following Pixar shareholder approval, the acquisition was completed on May 5, 2006. The transaction catapulted Jobs, who owned 49.65% of total share interest in Pixar, to Disney's largest individual shareholder with 7%, valued at $3.9 billion, and a new seat on its board of directors.[6][59] Jobs' new Disney holdings exceeded holdings belonging to Eisner, the previous top shareholder, who still held 1.7%; and Disney Director Emeritus Roy E. Disney, who held almost 1% of the corporation's shares. Pixar shareholders received 2.3 shares of Disney common stock for each share of Pixar common stock redeemed.[60]

As part of the deal, John Lasseter, by then Executive Vice President, became Chief Creative Officer (reporting directly to president and CEO Bob Iger and consulting with Disney Director Roy E. Disney) of both Pixar and Walt Disney Animation Studios (including its division Disneytoon Studios), as well as the Principal Creative Adviser at Walt Disney Imagineering, which designs and builds the company's theme parks.[59] Catmull retained his position as President of Pixar, while also becoming President of Walt Disney Animation Studios, reporting to Iger and Dick Cook, chairman of the Walt Disney Studios. Jobs's position as Pixar's chairman and chief executive officer was abolished, and instead, he took a place on the Disney board of directors.[61]

After the deal closed in May 2006, Lasseter revealed that Iger had felt that Disney needed to buy Pixar while watching a parade at the opening of Hong Kong Disneyland in September 2005.[62] Iger noticed that of all the Disney characters in the parade, none were characters that Disney had created within the last ten years since all the newer ones had been created by Pixar.[62] Upon returning to Burbank, Iger commissioned a financial analysis that confirmed that Disney had actually lost money on animation for the past decade, then presented that information to the board of directors at his first board meeting after being promoted from COO to CEO, and the board, in turn, authorized him to explore the possibility of a deal with Pixar.[63] Lasseter and Catmull were wary when the topic of Disney buying Pixar first came up, but Jobs asked them to give Iger a chance (based on his own experience negotiating with Iger in summer 2005 for the rights to