Prayer theme by BIG_SAM_HOE

Download: PrayerPS3.p3t

(1 backgrounds)

| Part of a series on |

| Prayer |

|---|

| Variants and related concepts |

| Aspects |

| Fundamental concepts |

| Prayer in various traditions (List) |

Prayer is an invocation or act that seeks to activate a rapport with an object of worship through deliberate communication. In the narrow sense, the term refers to an act of supplication or intercession directed towards a deity or a deified ancestor. More generally, prayer can also have the purpose of thanksgiving or praise, and in comparative religion is closely associated with more abstract forms of meditation and with charms or spells.[1]

Prayer can take a variety of forms: it can be part of a set liturgy or ritual, and it can be performed alone or in groups. Prayer may take the form of a hymn, incantation, formal creedal statement, or a spontaneous utterance in the praying person.

The act of prayer is attested in written sources as early as five thousand years ago. Today, most major religions involve prayer in one way or another; some ritualize the act, requiring a strict sequence of actions or placing a restriction on who is permitted to pray, while others teach that prayer may be practised spontaneously by anyone at any time.

Scientific studies regarding the use of prayer have mostly concentrated on its effect on the healing of sick or injured people. The efficacy of prayer in faith healing has been evaluated in numerous studies, with contradictory results.

Etymology[edit]

The English term prayer is from Medieval Latin: precaria, lit. 'petition, prayer'.[2] The Vulgate Latin is oratio, which translates Greek προσευχή[3] in turn the Septuagint translation of Biblical Hebrew תְּפִלָּה tĕphillah.[4]

Act of prayer[edit]

Various spiritual traditions offer a wide variety of devotional acts. There are morning and evening prayers, graces said over meals, and reverent physical gestures. Some Christians bow their heads and fold their hands. Some Native Americans regard dancing as a form of prayer.[5] Hindus chant mantras.[6] Jewish prayer may involve swaying back and forth and bowing.[7] Muslim prayer involves bowing, kneeling and prostration, while some Sufis whirl.[8] Quakers often keep silent.[9] Some pray according to standardized rituals and liturgies, while others prefer extemporaneous prayers; others combine the two.

Typologies and modalities[edit]

Christian circles often look to Friedrich Heiler (1892-1967), whose systematic Typology of Prayer lists six types of prayer: primitive, ritual, Greek cultural, philosophical, mystical, and prophetic.[10] Some forms of prayer require a prior ritualistic form of cleansing or purification, such as in ghusl and wudhu.[11]

Prayer may occur privately and individually (sometimes called affective prayer),[12] or collectively, shared by or led on behalf of fellow-believers of either a specific faith tradition or a broader grouping of people.[13] Prayer can be incorporated into a daily "thought life", in which one is in constant communication with a god. Some people pray throughout all that is happening during the day and seek guidance as the day progresses. This is actually regarded as a requirement in several Christian denominations,[14] although enforcement is neither possible nor desirable.[opinion] There can be many different answers to prayer, just as there are many ways to interpret an answer to a question, if there in fact comes an answer.[14] Some may experience audible, physical, or mental epiphanies. If indeed an answer comes, the time and place it comes is considered random.[citation needed]

Some traditions distinguish between contemplative and meditative prayer.[15]

Outward acts that may accompany prayer include anointing with oil;[16] ringing a bell;[17] burning incense or paper;[18] lighting a candle or candles; facing a specific direction (e.g., towards Mecca[19] or the East);[20] and making the sign of the cross. One less noticeable act related to prayer is fasting.

A variety of body postures may be assumed, often with specific meaning (mainly respect or adoration) associated with them: standing; sitting; kneeling; prostrate on the floor; eyes opened; eyes closed; hands folded or clasped; hands upraised; holding hands with others; a laying on of hands and others. Prayers may be recited from memory, read from a book of prayers, or composed spontaneously or "impromptu".[21] They may be said, chanted, or sung. They may or may not have a musical accompaniment. There may be a time of outward silence while prayers are offered mentally. Often, there are prayers to fit specific occasions, such as the blessing of a meal, the birth or death of a loved one, other significant events in the life of a believer, or days of the year that have special religious significance. Details corresponding to specific traditions are outlined below.

Origins and early history[edit]

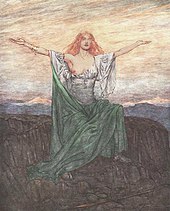

Anthropologically, the concept of prayer is closely related to that of surrender and supplication. The traditional posture of prayer in medieval Europe is kneeling or supine with clasped hands, in antiquity more typically with raised hands. The early Christian prayer posture was standing, looking up to heaven, with outspread arms and bare head. This is the pre-Christian, pagan prayer posture (except for the bare head, which was prescribed for males in I Corinthians 11:4, in Roman paganism, the head had to be covered in prayer). Certain Cretan and Cypriote figures of the Late Bronze Age, with arms raised, have been interpreted as worshippers. Their posture is similar to the "flight" posture, a crouching posture with raised hands related to the universal "hands up" gesture of surrender. The kneeling posture with clasped hands appears to have been introduced only with the beginning high medieval period, presumably adopted from a gesture of feudal homage.[23]

Although prayer in its literal sense is not used in animism, communication with the spirit world is vital to the animist way of life. This is usually accomplished through a shaman who, through a trance, gains access to the spirit world and then shows the spirits' thoughts to the people. Other ways to receive messages from the spirits include using astrology or contemplating fortune tellers and healers.[24]

Some of the oldest extant literature, such as the Kesh temple hymn (c. 26th century BC), is liturgy addressed to deities and thus technically "prayer". The Egyptian Pyramid Texts of about the same period similarly contain spells or incantations addressed to the gods. In the loosest sense, in the form of magical thinking combined with animism, prayer has been argued as representing a human cultural universal, which would have been present since the emergence of behavioral modernity, by anthropologists such as Sir Edward Burnett Tylor and Sir James George Frazer.[25]

Reliable records are available for the polytheistic religions of the Iron Age, most notably Ancient Greek religion, which strongly influenced Roman religion. These religious traditions were direct developments of the earlier Bronze Age religions. Ceremonial prayer was highly formulaic and ritualized.[26][27]

In ancient polytheism, ancestor worship is indistinguishable from theistic worship (see also euhemerism). Vestiges of ancestor worship persist, to a greater or lesser extent, in modern religious traditions throughout the world, most notably in Japanese Shinto, Vietnamese folk religion, and Chinese folk religion. The practices involved in Shinto prayer are heavily influenced by Buddhism; Japanese Buddhism has also been strongly influenced by Shinto in turn. Shinto prayers quite frequently consist of wishes or favors asked of the kami, rather than lengthy praises or devotions. The practice of votive offering is universal and is attested at least since the Bronze Age. In Shinto, this takes the form of a small wooden tablet, called an ema.

Prayers in Etruscan were used in the Roman world by augurs and other oracles long after Etruscan became a dead language. The Carmen Arvale and the Carmen Saliare are two specimens of partially preserved prayers that seem to have been unintelligible to their scribes and whose language is full of archaisms and difficult passages.[28]

Roman prayers and sacrifices were envisioned as legal bargains between deity and worshipper. The Roman principle was expressed as do ut des: "I give, so that you may give." Cato the Elder's treatise on agriculture contains many examples of preserved traditional prayers; in one, a farmer addresses the unknown deity of a possibly sacred grove, and sacrifices a pig in order to placate the god or goddess of the place and beseech his or her permission to cut down some trees from the grove.[29]

Celtic, Germanic and Slavic religions are recorded much later, and much more fragmentarily, than the religions of classical antiquity. They nevertheless show substantial parallels to the better-attested religions of the Iron Age. In the case of Germanic religion, the practice of prayer is reliably attested, but no actual liturgy is recorded from the early (Roman era) period. An Old Norse prayer is on record in the form of a dramatization in skaldic poetry. This prayer is recorded in stanzas 2 and 3 of the poem Sigrdrífumál, compiled in the 13th century Poetic Edda from earlier traditional sources, where the valkyrie Sigrdrífa prays to the gods and the earth after being woken by the hero Sigurd.[30] A prayer to Odin is mentioned in chapter 2 of the Völsunga saga where King Rerir prays for a child. In stanza 9 of the poem Oddrúnargrátr, a prayer is made to "kind wights, Frigg and Freyja, and many gods,[31] In chapter 21 of Jómsvíkinga saga, wishing to turn the tide of the Battle of Hjörungavágr, Haakon Sigurdsson eventually finds his prayers answered by the goddesses Þorgerðr Hölgabrúðr and Irpa.[32] Folk religion in the medieval period produced syncretisms between pre-Christian and Christian traditions. An example is the 11th-century Anglo-Saxon charm Æcerbot for the fertility of crops and land, or the medical Wið færstice.[33] The 8th-century Wessobrunn Prayer has been proposed as a Christianized pagan prayer and compared to the pagan Völuspá[34] and the Merseburg Incantations, the latter recorded in the 9th or 10th century but of much older traditional origins.[35]

In Australian Aboriginal mythology, prayers to the "Great Wit" are performed by the "clever men" and "clever women", or kadji.[citation needed] These Aboriginal shamans use maban or mabain, the material that is believed to give them their powers.[36] The Pueblo Indians are known to have used prayer sticks, that is, sticks with feathers attached as supplicatory offerings. The Hopi Indians used prayer sticks as well, but they attached to it a small bag of sacred meal.[37]

Approaches to prayer[edit]

Direct petitions[edit]

There are different forms of prayer. One of them is to directly appeal to a deity to grant one's requests.[38] Some have termed this as the social approach to prayer.[39]

Atheist arguments against prayer are mostly directed against petitionary prayer in particular. Daniel Dennett argued that petitionary prayer might have the undesirable psychological effect of relieving a person of the need to take active measures.[40]

This potential drawback manifests in extreme forms in such cases as Christian Scientists who rely on prayers instead of seeking medical treatment for family members for easily curable conditions which later result in death.[41]

Christopher Hitchens (2012) argued that praying to a god which is omnipotent and all-knowing would be presumptuous. For example, he interprets Ambrose Bierce's definition of prayer by stating that "the man who prays is the one who thinks that god has arranged matters all wrong, but who also thinks that he can instruct god how to put them right."[42]

Educational approach[edit]

In this view, prayer is not a conversation. Rather, it is meant to inculcate certain attitudes in the one who prays, but not to influence. Among Jews, this has been the approach of Rabbenu Bachya, Rabbi Yehuda Halevi, Joseph Albo, Samson Raphael Hirsch, and Joseph B. Soloveitchik. This view is expressed by Rabbi Nosson Scherman in the overview to the Artscroll Siddur (p. XIII).

Among Christian theologians, E.M. Bounds stated the educational purpose of prayer in every chapter of his book, The Necessity of Prayer. Prayer books such as the Book of Common Prayer are both a result of this approach and an exhortation to keep it.[43]

Rationalist approach[edit]

In this view, the ultimate goal of prayer is to help train a person to focus on divinity through philosophy and intellectual contemplation (meditation). This approach was taken by the Jewish scholar and philosopher Maimonides[44] and the other medieval rationalists.[45] It became popular in Jewish, Christian, and Islamic intellectual circles, but never became the most popular understanding of prayer among the laity in any of these faiths. In all three of these faiths today, a significant minority of people still hold to this approach.

In a rationalist approach, praying encompasses three aspects. First, 'logos', as the "idea" of the sender, secondly 'rhemata' as the words to express the idea, and thirdly 'rhemata' and 'logos', to where the idea is sent (e.g. to God, Allah). Thus praying is not a conversation with God, or Jesus but a one-way direction to the divine.[46] Among the Abrahamic religions, Islam, Orthodox Christianity and Hasidic Judaism are likely most adhering to this concept, also because it does not allow secondary mythologies, and has taken its spiritual roots from Hellenistic philosophy, particularly from Aristotle.[47]

Similarly in Hinduism, the different divinities are manifestations of one God with associated prayers. However, many Indians – particularly Hindus – believe that God can be manifest in people, including in people of lower castes, such as Sadhus.[48]

Experiential approach[edit]

In this approach, the purpose of prayer is to enable the person praying to gain a direct experience of the recipient of the prayer (or as close to direct as a specific theology permits). This approach is very significant in Christianity and widespread in Judaism (although less popular theologically). In Eastern Orthodoxy, this approach is known as hesychasm. It is also widespread in Sufi Islam, and in some forms of mysticism. It has some similarities with the rationalist approach, since it can also involve contemplation, although the contemplation is not generally viewed as being as rational or intellectual.

Christian and Roman Catholic traditions also include an experiential approach to prayer within the practice of lectio divina. Historically a Benedictine practice, lectio divina involves the following steps: a short scripture passage is read aloud; the passage is meditated upon using the mind to place the listener within a relationship or dialogue with the text; recitation of a prayer; and concludes with contemplation. The Catechism of the Catholic Church describes prayer and meditation as follows:[49]

Meditation engages thought, imagination, emotion, and desire. This mobilization of faculties is necessary in order to deepen our convictions of faith, prompt the conversion of our heart, and strengthen our will to follow Christ. Christian prayer tries above all to meditate on the mysteries of Christ, as in lectio divina or the rosary. This form of prayerful reflection is of great value, but Christian prayer should go further: to the knowledge of the love of the Lord Jesus, to union with him.

The experience of God within Christian mysticism has been contrasted with the concept of experiential religion or mystical experience because of a long history or authors living and writing about experience with the divine in a manner that identifies God as unknowable and ineffable, the language of such ideas could be characterized paradoxically as "experiential", as well as without the phenomena of experience.[50]

The notion of "religious experience" can be traced back to William James, who used a term called "religious experience" in his book, The Varieties of Religious Experience.[51][citation not found] The origins of the use of this term can be dated further back.

In the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries, several historical figures put forth very influential views that religion and its beliefs can be grounded in experience itself. While Kant held that moral experience justified religious beliefs, John Wesley in addition to stressing individual moral exertion thought that the religious experiences in the Methodist movement (paralleling the Romantic Movement) were foundational to religious commitment as a way of life.[52] According to catholic doctrine, Methodists lack a ritualistic and rational approach to praying but rely on individualistic and moralistic forms of worship in direct conversation