Goonies theme by MikeGORO aka PorkSword79

Download: Goonies.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

Redirect to:

This page is a redirect. The following categories are used to track and monitor this redirect:

|

The #1 spot for Playstation themes!

Goonies theme by MikeGORO aka PorkSword79

Download: Goonies.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

Redirect to:

This page is a redirect. The following categories are used to track and monitor this redirect:

|

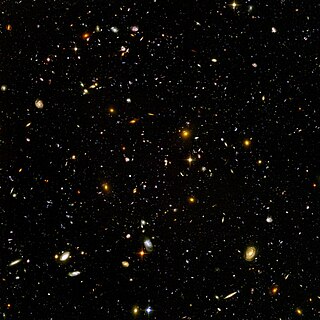

2001: A Space Odyssey theme by YASAI

Download: 2001.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

| 2001: A Space Odyssey | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Robert McCall | |

| Directed by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Produced by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Geoffrey Unsworth |

| Edited by | Ray Lovejoy |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 139 minutes[2] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $10.5 million |

| Box office | $146 million |

2001: A Space Odyssey is a 1968 epic science fiction film produced and directed by Stanley Kubrick. The screenplay was written by Kubrick and science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke, and was inspired by Clarke's 1951 short story "The Sentinel" and other of his short stories. Clarke also published a novelisation of the film, in part written concurrently with the screenplay, after the film's release. The film stars Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, William Sylvester, and Douglas Rain and follows a voyage by astronauts, scientists, and the sentient supercomputer HAL to Jupiter to investigate an alien monolith.

The film is noted for its scientifically accurate depiction of space flight, pioneering special effects, and ambiguous imagery. Kubrick avoided conventional cinematic and narrative techniques; dialogue is used sparingly, and there are long sequences accompanied only by music. The soundtrack incorporates numerous works of classical music, including pieces by composers such as Richard Strauss, Johann Strauss II, Aram Khachaturian, and György Ligeti.

The film received diverse critical responses, ranging from those who saw it as darkly apocalyptic to those who saw it as an optimistic reappraisal of the hopes of humanity. Critics noted its exploration of themes such as human evolution, technology, artificial intelligence, and the possibility of extraterrestrial life. It was nominated for four Academy Awards, winning Kubrick the award for his direction of the visual effects.[3] The film is now widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential films ever made. In 1991, it was selected by the United States Library of Congress for preservation in the National Film Registry. In 2022, 2001: A Space Odyssey placed in the top ten of Sight & Sound's decennial critics' poll, and topped their directors' poll. A sequel, 2010: The Year We Make Contact, was released in 1984, based on the novel 2010: Odyssey Two.

In a prehistoric veld, a tribe of hominins is driven away from its water hole by a rival tribe. The next day, they find an alien monolith has appeared in their midst. The tribe then learn how to use a bone as a weapon and, after their first hunt, return to drive their rivals away with it.

Millions of years later, Dr Heywood Floyd, Chairman of the United States National Council of Astronautics, travels to Clavius Base, an American lunar outpost. During a stopover at Space Station Five, he meets Russian scientists who are concerned that Clavius seems to be unresponsive. He refuses to discuss rumours of an epidemic at the base. At Clavius, Heywood addresses a meeting of personnel to whom he stresses the need for secrecy regarding their newest discovery. His mission is to investigate a recently found artefact, a monolith buried four million years earlier near the lunar crater Tycho. As he and others examine the object and are taking photographs, it emits a high-powered radio signal.

Eighteen months later, the American spacecraft Discovery One is bound for Jupiter, with mission pilots and scientists Dr Dave Bowman and Dr Frank Poole on board, along with three other scientists in suspended animation. Most of Discovery's operations are controlled by HAL, a HAL 9000 computer with a human-like personality. When HAL reports the imminent failure of an antenna control device, Dave retrieves it in an extravehicular activity (EVA) pod, but finds nothing wrong. HAL suggests reinstalling the device and letting it fail so the problem can be verified. Mission Control advises the astronauts that results from their backup 9000 computer indicate that HAL has made an error, but HAL blames it on human error. Concerned about HAL's behaviour, Dave and Frank enter an EVA pod so they can talk in private without HAL overhearing. They agree to disconnect HAL if he is proven wrong. HAL follows their conversation by lip reading.

While Frank is floating away from his pod to replace the antenna unit, HAL takes control of the pod and attacks him, sending Frank tumbling away from the ship with a severed air line. Dave takes another pod to rescue Frank. While he is outside, HAL turns off the life support functions of the crewmen in suspended animation, killing them. When Dave returns to the ship with Frank's body, HAL refuses to let him back in, stating that their plan to deactivate him jeopardises the mission. Dave releases Frank's body and opens the ship's emergency airlock with his remote manipulators. Lacking a helmet for his spacesuit, he positions his pod carefully so that when he jettisons the pod's door, he is propelled by the escaping air across the vacuum into Discovery's airlock. He enters HAL's processor core and begins disconnecting most of HAL's circuits, ignoring HAL's pleas to stop. When he is finished, a prerecorded video by Heywood plays, revealing that the mission's actual objective is to investigate the radio signal sent from the monolith to Jupiter.

At Jupiter, Dave finds a third, much larger monolith orbiting the planet. He leaves Discovery in an EVA pod to investigate. He is pulled into a vortex of coloured light and observes bizarre astronomical phenomena and strange landscapes of unusual colours as he passes by. Finally he finds himself in a large neoclassical bedroom where he sees, and then becomes, older versions of himself: first standing in the bedroom, middle-aged and still in his spacesuit, then dressed in leisure attire and eating dinner, and finally as an old man lying in bed. A monolith appears at the foot of the bed, and as Dave reaches for it, he is transformed into a foetus enclosed in a transparent orb of light floating in space above the Earth.

After completing Dr. Strangelove (1964), director Stanley Kubrick told a publicist from Columbia Pictures that his next project would be about extraterrestrial life,[9][10] and resolved to make "the proverbial good science fiction movie".[11] How Kubrick became interested in creating a science fiction film is far from clear.[12] Biographer John Baxter notes possible inspirations in the late 1950s, including British productions featuring dramas on satellites and aliens modifying early humans, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's big budget CinemaScope production Forbidden Planet, and the slick widescreen cinematography and set design of Japanese kaiju (monster movie) productions (such as Ishirō Honda and Eiji Tsuburaya's Godzilla films and Koji Shima's Warning from Space).[12]

Kubrick obtained financing and distribution from the American studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer with the selling point that the film could be marketed in their ultra-widescreen Cinerama format, recently debuted with their How the West Was Won.[13][14][12] It would be filmed and edited almost entirely in southern England, where Kubrick lived, using the facilities of MGM-British Studios and Shepperton Studios. MGM had subcontracted the production of the film to Kubrick's production company to qualify for the Eady Levy, a UK tax on box-office receipts used at the time to fund the production of films in Britain.[15] In a draft version of a contract with Kubrick's production company in May 1965, MGM suggested Alfred Hitchcock, Billy Wilder and David Lean as possible replacements for Kubrick if he was unavailable.[16]

Kubrick's decision to avoid the fanciful portrayals of space found in standard popular science fiction films of the time led him to seek more realistic and accurate depictions of space travel. Illustrators such as Chesley Bonestell, Roy Carnon, and Richard McKenna were hired to produce concept drawings, sketches, and paintings of the space technology seen in the film.[17][18] Two educational films, the National Film Board of Canada's 1960 animated short documentary Universe and the 1964 New York World's Fair movie To the Moon and Beyond, were major influences.[17]

According to biographer Vincent LoBrutto, Universe was a visual inspiration to Kubrick.[19] The 29-minute film, which had also proved popular at NASA for its realistic portrayal of outer space, met "the standard of dynamic visionary realism that he was looking for". Wally Gentleman, one of the special-effects artists on Universe, worked briefly on 2001. Kubrick also asked Universe co-director Colin Low about animation camerawork, with Low recommending British mathematician Brian Salt, with whom Low and Roman Kroitor had previously worked on the 1957 still-animation documentary City of Gold.[20][21] Universe's narrator, actor Douglas Rain, was cast as the voice of HAL.[22] For the role of Heywood Floyd, MGM suggested casting a well-known actor such as Henry Fonda or George C. Scott.[23]

After pre-production had begun, Kubrick saw To the Moon and Beyond, a film shown in the Transportation and Travel building at the 1964 World's Fair. It was filmed in Cinerama 360 and shown in the "Moon Dome". Kubrick hired the company that produced it, Graphic Films Corporation—which had been making films for NASA, the US Air Force, and various aerospace clients—as a design consultant.[17] Graphic Films' Con Pederson, Lester Novros, and background artist Douglas Trumbull airmailed research-based concept sketches and notes covering the mechanics and physics of space travel, and created storyboards for the space flight sequences in 2001.[17] Trumbull became a special effects supervisor on 2001.[17]

Searching for a collaborator in the science fiction community for the writing of the script, Kubrick was advised by a mutual acquaintance, Columbia Pictures staff member Roger Caras, to talk to writer Arthur C. Clarke, who lived in Ceylon. Although convinced that Clarke was "a recluse, a nut who lives in a tree", Kubrick allowed Caras to cable the film proposal to Clarke. Clarke's cabled response stated that he was "frightfully interested in working with [that] enfant terrible", and added "what makes Kubrick think I'm a recluse?"[19][24] Meeting for the first time at Trader Vic's in New York on 22 April 1964, the two began discussing the project that would take up the next four years of their lives.[25] Clarke kept a diary throughout his involvement with 2001, excerpts of which were published in 1972 as The Lost Worlds of 2001.[26]

Kubrick told Clarke he wanted to make a film about "Man's relationship to the universe",[27] and was, in Clarke's words, "determined to create a work of art which would arouse the emotions of wonder, awe ... even, if appropriate, terror".[25] Clarke offered Kubrick six of his short stories, and by May 1964, Kubrick had chosen "The Sentinel" as the source material for the film. In search of more material to expand the film's plot, the two spent the rest of 1964 reading books on science and anthropology, screening science fiction films, and brainstorming ideas.[28] They created the plot for 2001 by integrating several different short story plots written by Clarke, along with new plot segments requested by Kubrick for the film development, and then combined them all into a single script for 2001.[29][30] Clarke said that his 1953 story "Encounter in the Dawn" inspired the film's "Dawn of Man" sequence.[31]

Kubrick and Clarke privately referred to the project as How the Solar System Was Won, a reference to how it was a follow-on to MGM's Cinerama epic How the West Was Won.[12] On 23 February 1965, Kubrick issued a press release announcing the title as Journey Beyond The Stars.[32] Other titles considered included Universe, Tunnel to the Stars, and Planetfall. Expressing his high expectations for the thematic importance which he associated with the film, in April 1965, eleven months after they began working on the project, Kubrick selected 2001: A Space Odyssey; Clarke said the title was "entirely" Kubrick's idea.[33] Intending to set the film apart from the "monsters-and-sex" type of science-fiction films of the time, Kubrick used Homer's The Odyssey as both a model of literary merit and a source of inspiration for the title. Kubrick said, "It occurred to us that for the Greeks the vast stretches of the sea must have had the same sort of mystery and remoteness that space has for our generation."[34]

How much would we appreciate La Gioconda today if Leonardo had written at the bottom of the canvas: "This lady is smiling slightly because she has rotten teeth" — or "because she's hiding a secret from her lover"? It would shut off the viewer's appreciation and shackle him to a reality other than his own. I don't want that to happen to 2001.

Originally, Kubrick and Clarke had planned to develop a 2001 novel first, free of the constraints of film, and then write the screenplay. They planned the writing credits to be "Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, based on a novel by Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick" to reflect their preeminence in their respective fields.[36] In practice, the screenplay developed in parallel with the novel, with only some elements being common to both. In a 1970 interview, Kubrick said:

There are a number of differences between the book and the movie. The novel, for example, attempts to explain things much more explicitly than the film does, which is inevitable in a verbal medium. The novel came about after we did a 130-page prose treatment of the film at the very outset. ... Arthur took all the existing material, plus an impression of some of the rushes, and wrote the novel. As a result, there's a difference between the novel and the film ... I think that the divergences between the two works are interesting.[37]

In the end, Clarke and Kubrick wrote parts of the novel and screenplay simultaneously, with the film version being released before the book version was published. Clarke opted for clearer explanations of the mysterious monolith and Star Gate in the novel; Kubrick made the film more cryptic by minimising dialogue and explanation.[38] Kubrick said the film is "basically a visual, nonverbal experience" that "hits the viewer at an inner level of consciousness, just as music does, or painting".[39]

The screenplay credits were shared whereas the 2001 novel, released shortly after the film, was attributed to Clarke alone. Clarke wrote later that "the nearest approximation to the complicated truth" is that the screenplay should be credited to "Kubrick and Clarke" and the novel to "Clarke and Kubrick".[40] Early reports about tensions involved in the writing of the film script appeared to reach a point where Kubrick was allegedly so dissatisfied with the collaboration that he approached other writers who could replace Clarke, including Michael Moorcock and J. G. Ballard. But they felt it would be disloyal to accept Kubrick's offer.[41] In Michael Benson's 2018 book Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke, and the Making of a Masterpiece, the actual relation between Clarke and Kubrick was more complex, involving an extended interaction of Kubrick's multiple requests for Clarke to write new plot lines for various segments of the film, which Clarke was expected to withhold from publication until after the release of the film while receiving advances on his salary from Kubrick during film production. Clarke agreed to this, though apparently he did make several requests for Kubrick to allow him to develop his new plot lines into separate publishable stories while film production continued, which Kubrick consistently denied on the basis of Clarke's contractual obligation to withhold publication until release of the film.[30]

Astronomer Carl Sagan wrote in his 1973 book The Cosmic Connection that Clarke and Kubrick had asked him how to best depict extraterrestrial intelligence. While acknowledging Kubrick's desire to use actors to portray humanoid aliens for convenience's sake, Sagan argued that alien life forms were unlikely to bear any resemblance to terrestrial life, and that to do so would introduce "at least an element of falseness" to the film. Sagan proposed that the film should simply suggest extraterrestrial superintelligence, rather than depict it. He attended the premiere and was "pleased to see that I had been of some help".[42] Sagan had met with Clarke and Kubrick only once, in 1964; and Kubrick subsequently directed several attempts to portray credible aliens, only to abandon the idea near the end of post-production. Benson asserts it is unlikely that Sagan's advice had any direct influence.[30] Kubrick hinted at the nature of the mysterious unseen alien race in 2001 by suggesting that given millions of years of evolution, they progressed from biological beings to "immortal machine entities" and then into "beings of pure energy and spirit" with "limitless capabilities and ungraspable intelligence".[43]

In a 1980 interview (not released during Kubrick's lifetime), Kubrick explains one of the film's closing scenes, where Bowman is depicted in old age after his journey through the Star Gate:

The idea was supposed to be that he is taken in by godlike entities, creatures of pure energy and intelligence with no shape or form. They put him in what I suppose you could describe as a human zoo to study him, and his whole life passes from that point on in that room. And he has no sense of time. ... [W]hen they get finished with him, as happens in so many myths of all cultures in the world, he is transformed into some kind of super being and sent back to Earth, transformed and made some kind of superman. We have to only guess what happens when he goes back. It is the pattern of a great deal of mythology, and that is what we were trying to suggest.[44]

The script went through many stages. In early 1965, when backing was secured for the film, Clarke and Kubrick still had no firm idea of what would happen to Bowman after the Star Gate sequence. Initially all of Discovery's astronauts were to survive the journey; by 3 October, Clarke and Kubrick had decided to make Bowman the sole survivor and have him regress to infancy. By 17 October, Kubrick had come up with what Clarke called a "wild idea of slightly fag robots who create a Victorian environment to put our heroes at their ease".[40] HAL 9000 was originally named Athena after the Greek goddess of wisdom and had a feminine voice and persona.[40]

Early drafts included a prologue containing interviews with scientists about extraterrestrial life,[45] voice-over narration (a feature in all of Kubrick's previous films),[a] a stronger emphasis on the prevailing Cold War balance of terror, and a different and more explicitly explained breakdown for HAL.[47][48] Other changes include a different monolith for the "Dawn of Man" sequence, discarded when early prototypes did not photograph well; the use of Saturn as the final destination of the Discovery mission rather than Jupiter, discarded when the special effects team could not develop a convincing rendition of Saturn's rings; and the finale of the Star Child exploding nuclear weapons carried by Earth-orbiting satellites,[48] which Kubrick discarded for its similarity to his previous film, Dr. Strangelove.[45][48] The finale and many of the other discarded screenplay ideas survived in Clarke's novel.[48]

Kubrick made further changes to make the film more nonverbal, to communicate on a visual and visceral level rather than through conventional narrative.[35] By the time shooting began, Kubrick had removed much of the dialogue and narration.[49] Long periods without dialogue permeate the film: the film has no dialogue for roughly the first and last twenty minutes,[50] as well as for the 10 minutes from Floyd's Moonbus landing near the monolith until Poole watches a BBC newscast on Discovery. What dialogue remains is notable for its banality (making the computer HAL seem to have more emotion than the humans) when juxtaposed with the epic space scenes.[49] Vincent LoBrutto wrote that Clarke's novel has its own "strong narrative structure" and precision, while the narrative of the film remains symbolic, in accord with Kubrick's final intentions.[51]

Principal photography began on 29 December 1965, in Stage H at Shepperton Studios, Shepperton, England. The studio was chosen because it could house the 60-by-120-by-60-foot (18 m × 37 m × 18 m) pit for the Tycho crater excavation scene, the first to be shot. In January 1966, the production moved to the smaller MGM-British Studios in Borehamwood, where the live-action and special-effects filming was done, starting with the scenes involving Floyd on the Orion spaceplane;[52] it was described as a "huge throbbing nerve center ... with much the same frenetic atmosphere as a Cape Kennedy blockhouse during the final stages of Countdown."[53] The only scene not filmed in a studio—and the last live-action scene shot for the film—was the skull-smashing sequence, in which Moonwatcher (Richter) wields his newfound bone "weapon-tool" against a pile of nearby animal bones. A small elevated platform was built in a field near the studio so that the camera could shoot upward with the sky as background, avoiding cars and trucks passing by in the distance.[54][55] The Dawn of Man sequence that opens the film was shot at Borehamwood with John Alcott as cinematographer after Geoffrey Unsworth left to work on other projects.[56][57] The still photographs used as backgrounds for the Dawn of Man sequence were taken at the Spitzkoppe mountains in what was then South West Africa.[58][59]

Filming of actors was completed in September 1967,[60] and from June 1966 until March 1968, Kubrick spent most of his time working on the 205 special-effects shots in the film.[37] He ordered the special-effects technicians to use the painstaking process of creating all visual effects seen in the film "in camera", avoiding degraded picture quality from the use of blue screen and travelling matte techniques. Although this technique, known as "held takes", resulted in a much better image, it meant exposed film would be stored for long periods of time between shots, sometimes as long as a year.[61] In March 1968, Kubrick finished the "pre-premiere" editing of the film, making his final cuts just days before the film's general release in April 1968.[37]

The film was announced in 1965 as a "Cinerama"[62] film and was photographed in Super Panavision 70 (which uses a 65 mm negative combined with spherical lenses to create an aspect ratio of 2.20:1). It would eventually be released in a limited "roadshow" Cinerama version, then in 70 mm and 35 mm versions.[63][64] Colour processing and 35 mm release prints were done using Technicolor's dye transfer process. The 70 mm prints were made by MGM Laboratories, Inc. on Metrocolor. The production was $4.5 million over the initial $6 million budget and 16 months behind schedule.[65] For the opening sequence involving tribes of apes, professional mime D

Ninja Gaiden Sigma theme by YASAI

Download: NinjaGaidenSigma.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune theme by Marconelly

Download: UnchartedDrakesFortune_2.p3t

(4 backgrounds)

| Uncharted: Drake's Fortune | |

|---|---|

North American cover art featuring the titular protagonist Nathan Drake in a jungle | |

| Developer(s) | Naughty Dog |

| Publisher(s) | Sony Computer Entertainment |

| Director(s) | Amy Hennig |

| Designer(s) | Richard Lemarchand Hirokazu Yasuhara |

| Programmer(s) |

|

| Artist(s) | |

| Writer(s) |

|

| Composer(s) | Greg Edmonson |

| Series | Uncharted |

| Platform(s) | PlayStation 3 |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Action-adventure, third-person shooter |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

Uncharted: Drake's Fortune is a 2007 action-adventure game developed by Naughty Dog and published by Sony Computer Entertainment. It is the first game in the Uncharted series and was released in November 2007 for PlayStation 3. The game follows Nathan Drake, the supposed descendant of explorer Sir Francis Drake, as he searches for the lost treasure of El Dorado with journalist Elena Fisher and mentor Victor Sullivan.

The development of Uncharted: Drake's Fortune began in 2005, and saw Naughty Dog altering their approach to development, as they sought to create a humanized video game that was distinct from their other entries, settling on an action-adventure game with platforming elements and a third-person perspective. The team regularly updated or wholly changed various aspects related to the story, coding, and the game's design which lead to delays. The development team found influence for many of the game's aesthetic elements from film, pulp magazines, and movie serials.

Extensively marketed as a PlayStation exclusive, Uncharted: Drake's Fortune received generally favorable reviews, with praise for its technical achievements, cast, characters, story, music, and production values, drawing similarities to blockbuster films. It faced some criticism for its graphical issues, short length, vehicle sections, and marked difficulty. Uncharted: Drake's Fortune sold one million copies after ten weeks of release. It was followed by the sequel Uncharted 2: Among Thieves in 2009, and was re-released on PlayStation 4 as part of Uncharted: The Nathan Drake Collection.

The central character of Uncharted: Drake's Fortune is Nathan Drake (voiced by Nolan North), a renowned adventurer who claims to be the descendant of the famous explorer Sir Francis Drake. Together with his mentor Victor Sullivan (voiced by Richard McGonagle) and journalist Elena Fisher (voiced by Emily Rose), Drake embarks on a quest to discover the hidden riches of El Dorado.[3]

Treasure hunter Nathan "Nate" Drake, accompanied by reporter Elena Fisher, recovers the coffin of his self-proclaimed ancestor Sir Francis Drake, having located it from coordinates inscribed on a family heirloom: a ring Nate wears around his neck.[4] The coffin contains Sir Francis' diary, which gives the location of El Dorado. Pirates attack and destroy Nate's boat, but Nate's friend and mentor, Victor "Sully" Sullivan, rescues the two in his seaplane. Fearing Elena's reporting will attract potential rivals, Nate and Sully abandon her at a dock.

Nate and Sully discover an alcove that once held a large statue after following the diary to the indicated spot, and realize that El Dorado is not a city but rather a golden idol.[5] They find a Nazi U-boat, which contains a page from Drake's diary showing the statue was taken to an island. However, mercenaries led by criminal Gabriel Roman (Simon Templeman), to whom Sully owes a substantial debt, and his lieutenant Atoq Navarro (Robin Atkin Downes), intercept Nate and Sully. Sully is shot in the chest and collapses, but Nate manages to escape, encounters Elena, and flies with her to the island.[6]

On the way, anti-aircraft fire forces Elena and Nate to bail out and they are separated. After retrieving supplies from the wrecked seaplane, Nate heads toward an old fort to find Elena. After Nate is briefly captured by pirates led by his old associate Eddy Raja (James Sie), Elena breaks him free and they flee to the island's old customs house. After finding records showing the statue was moved further inland to the monastery, they find that Sully is somehow alive and accompanying Roman and Navarro.[7] Nate and Elena find and rescue Sully who, having survived due to Drake's diary blocking the bullet, explains he was buying time for Nate by misleading Roman.

Searching through a mausoleum, Nate overhears an argument between Roman, Navarro, and Eddy, revealing that Roman hired Eddy to capture Nate and secure the island, with the reward being a share of El Dorado. Following Nate's escape, Roman doubts Eddy's abilities and ignores his claim that something cursed on the island is killing his men, leading him to dismiss Eddy and his crew. Regrouping, Nate and Elena find a passage leading to a treasure vault, in which they find the body of Drake, assuming that he died searching for the treasure. They encounter a terrified Eddy and a crew member, shortly before they are attacked by mutated humans who kill the crew member; despite Nate's efforts, Eddy is also killed when one drags him into a pit.

Nate and Elena escape and find themselves in an abandoned German bunker. Venturing into the base, Nate discovers that the Germans had sought the statue during World War II, but like the Spaniards before them, became cursed by the statue, causing them to become mutants. Sir Francis, knowing of the statue's power, attempted to keep it on the island by destroying the ships and flooding the city, before he too was killed by the mutants.[8]

Nate returns to find Elena has been captured by Roman and Navarro. Regrouping with Sully, he fails to stop them from reaching the statue. Navarro, aware of the curse, tricks Roman into opening the statue, revealing it to be a sarcophagus containing a mummy infected with an airborne mutagenic virus. Upon Roman turning into one of the mutants, Navarro kills him and takes control of his men. Berating Nate's group for not being imaginative, he plans to sell the virus as a biological weapon.[9] Nate jumps onto the sarcophagus and rides it as it is airlifted onto a boat in the bay. He engages and defeats Navarro and manages to sink both the sarcophagus and him to the bottom of the ocean.[10] Sully arrives, and after Nate and Elena display affection towards each other, they leave the island with several chests of treasure.[11]

Gameplay in Uncharted is a combination of action-adventure gameplay elements and some 3D platforming with a third-person perspective. Platforming elements allow Nate to jump, swim, grab and move along ledges, climb and swing from ropes, and perform other acrobatic actions that allow players to make their way along the ruins in the various areas of the island that Drake explores.[12]

When facing enemies, the player can either use melee and combo attacks at close range to take out foes or can opt to use weapons.[12] Melee attacks comprise a variety of single punches, while combo attacks are activated through specific sequences of button presses that, when timed correctly, offer much greater damage; the most damaging of these is the specific "brutal combo", which forces enemies to drop twice the ammunition they would normally leave.[12] Nate can only carry one pistol and one rifle at a time, and there is a limited amount of ammunition per gun. Picking up a different firearm switches that weapon for the new one. Grenades are also available at certain points, and the height of the aiming arc is adjusted by tilting the Sixaxis controller up or down. These third-person perspective elements were compared by several reviewers to Gears of War,[3][12] in that the player can have Drake take cover behind walls, and use either blind fire or aimed fire to kill enemies. In common with the aforementioned game, Uncharted lacks an actual on-screen health bar; instead, when the player takes damage, the graphics begin to lose color. While resting or taking cover for a brief period, Drake's health level, indicated by the screen color, returns to normal.[12]

The game also includes vehicle sections, where Drake must protect the jeep he and Elena are in using a mounted turret, and where Drake and Elena ride a jet ski along water-filled routes while avoiding enemy fire and explosive barrels. While players direct Drake in driving the jet ski, they may also control Elena by aiming the gun in order to use her weapon — either the grenade launcher or the Beretta, depending on the chapter — in defense, or to clear the barrels from their path.[12]

The game also features reward points, which can be gained by collecting 60 hidden treasures in the game that glimmer momentarily[13] or by completing certain accomplishments, such as achieving a number of kills using a specific weapon, performing a number of headshots, or using specific methods of killing enemies.[14] In subsequent playthroughs of the game, the player can use these rewards points to unlock special options; these include in-game bonuses such as alternate costumes and unlimited ammunition[13] but also non-game extras, such as making-of videos and concept art.[15] There are also several references to other Naughty Dog games, especially the Jak and Daxter series; this is done through the "Ottsel" branding on Drake and Fisher's wetsuits,[16] a reference to the species that mixes otter and weasel found in the game, and the strange relic found in one of the earlier chapters, which is actually a precursor orb from the same series.

The game is censored when playing on a Japanese console to remove blood, which normally appears when shooting enemies; this follows the trend of other censored console games in the region, such as Dead Rising and Resistance: Fall of Man.[17]

After completing Jak 3, Naughty Dog assembled their most technically talented staff members and began development of Uncharted: Drake's Fortune under the codename Big.[18][19] The game's development commenced in 2005 and it was in full production for about two years, with a small team of engineers working on the game for about a year beforehand.[20] Naughty Dog decided to create a brand new IP rather than opt to develop a PlayStation 3 Jak and Daxter game—they wanted to create a franchise suitable for the new hardware, in order to develop such ideas as realistic human characters instead of stylized ones owing to limitations of previous hardware, as well as create something "fresh and interesting", although termed as 'stylized realism'.[20] Inspiration was drawn from various sources in the action and adventure genres: pulp magazines, movie serials, and more contemporary titles like Indiana Jones and National Treasure.[21] The team felt the sources shared themes of mystery and "what-if scenarios" that romanticized adventure and aimed to include those in Uncharted.[18]

The game was first unveiled at E3 2006.[22] From early previews of the game, inevitable comparisons of elements such as platforming and shooting between Uncharted and the well-known Tomb Raider series were drawn, earning the title the nickname of "Dude Raider".[21][23] However, the developers saw their game as concentrating more on third-person cover-based play, in contrast to Tomb Raider's "auto-aiming" play and greater puzzle-solving elements.[20] Other influences they cited include Resident Evil 4,[24] Kill Switch, and Gears of War.[25] Throughout the game's development the staff tried to remain flexible and detached from the original design concepts; attention was focused on the features that worked well, while features that did not work were removed.[26] The development team intended the game's main setting, the island, to play a big role in the overall experience. Feeling too many games used bleak, dark settings with monochromatic color schemes, they wanted the island to be a vibrant, believable game world that immersed the player and encouraged exploration.[18]

In designing the characters, the artists aimed for a style that was photorealistic.[21] The creators envisioned the main protagonist, Nathan Drake, as more of an everyman character than Lara Croft, shown as clearly under stress in the game's many firefights, with no special training and constantly living at the edge of his abilities.[20][23] Director Amy Hennig felt a heavily armored, "tough as nails" protagonist with a large weapon was not a suitable hero and decided a "tenacious and resourceful" character would portray more human qualities. Supporting characters (Elena Fisher and Victor Sullivan) were included to avoid a dry and emotionless story.[21] Fisher's character underwent changes during development; in early trailers for the game, the character had dark brown hair, but ultimately the color changed to blonde and the style was altered.[27][28] The writing of the story was led by Hennig with help from Neil Druckmann and Josh Scherr.[29] The lead game designer was Richard Lemarchand,[30] with the game co-designed by Hirokazu Yasuhara, a former Sega game designer best known for designing the early Sonic the Hedgehog games.[31]

The game went gold in the middle of October 2007.[20] A demo was then released on November 8 on the PlayStation Network[32] before its final release on November 19 in North America, December 6 in Australia, and December 7 in Europe.[33] The demo was first placed on the North American store, and was initially region-locked such that it would only play on a North American PS3,[34] but this was later confirmed as a mistake, as the developers were apparently unaware that people from different regions could sign up for a North American account and download the demo; a region-free demo was released soon after.[35]

Uncharted uses the Cell microprocessor to generate dozens of layered character animations to portray realistic expressions and fluid movements, which allow for responsive player control.[36] The PlayStation 3's graphics processing unit, the RSX Reality Synthesizer, employed several functions to provide graphical details that helped immerse the player into the game world: lighting models, pixel shaders, dynamic real-time shadowing, and advanced water simulation.[36] The new hardware allowed for processes that the team had never used in PlayStation 2 game development and required them to quickly familiarize themselves with the new techniques; for example, parallel processing and pixel shaders. While Blu-ray afforded greater storage space, the team became concerned with running out of room several times — Uncharted used more and bigger textures than previous games, and included several languages on the disc.[37] Gameplay elements requiring motion sensing, such as throwing grenades and walking across beams, or rear-ending massive logs up the scooter, were implemented to take advantage of the Sixaxis controller.[18] A new PlayStation 3 controller, the DualShock 3, was unveiled at the 2007 Tokyo Game Show, and featured force feedback vibration. Uncharted was also on display at the show with demonstrations that implemented limited support for vibration.[38]

Being Naughty Dog's first PlayStation 3 game, the project required the company to familiarize themselves with the new hardware and resulted in several development mistakes.[37] The switch from developing for the PlayStation 2 to the PlayStation 3 prompted the staff to implement changes to their development technology. Naughty Dog switched to the industry standard language C++ to participate in technology sharing among Sony's first-party developers—the company had previously used their own proprietary programming language GOAL, a Lisp-based language. In rewriting their game code, they decided to create new programming tools as well. This switch, however, delayed the team's progress in developing a prototype, as the new tools proved to be unreliable and too difficult to use. Ten months into full production, the team decided to recreate the game's pipeline, the chain of processing elements designed to progress data through a system. In retrospect, Naughty Dog's Co-President Evan Wells considered this the greatest improvement to the project.[26] Additionally, the animation blending system was rewritten several times to obtain the desired character animations.[18]

The game was patched on August 4, 2008 in Europe and North America to version 1.01 to include support for the PlayStation 3's Trophy system.[39] There are 47 trophies in the game that match the medals that can already be won in the game and one further trophy, the Platinum trophy, awarded when all other trophies have been collected; Uncharted was the first Naughty Dog game to include the Platinum trophy type.[40] Similar to other PlayStation 3 titles that receive trophy support via downloaded patches, players must start a new save game to be awarded trophies, regardless of how many medals they received in previous playthroughs. This was enforced because the developers wanted to avoid the sharing of save data in order to gain trophies they did not earn.[41] The patch was described as "incredibly easy" to implement, owing to the game already containing preliminary support for Trophies via its Medals system; it was also stated that these hooks were already included due to Naughty Dog's belief that Sony would roll out the Trophy system before the game's launch in November 2007.[41] Despite mentioning that the game was developed as a franchise and that it lent itself to episodic content,[20] it was later stated that no downloadable content would be made for Uncharted.[42]

During the Closed Beta of PlayStation Home on October 11, 2008, Naughty Dog released an Uncharted themed game space for PlayStation Home. This space is "Sully's Bar" from the game. In this space, users can play an arcade mini-game called "Mercenary Madness", which during the Closed Beta, there were rewards. The rewards were removed with the release of the Home Open Beta. There are also three other rooms in this space: during the Closed Beta, users had to find out codes for the doors that accessed these rooms. The code entry to the rooms was also removed with the release of the Home Open Beta. The three other rooms are the "Artifact Room", "Archives", and "Smuggler's Den". There is an artifact viewer in the Archives and Smuggler's Den rooms. Also in the Archives, there is a video screen that previews Uncharted 2: Among Thieves. The Artifact Room only features seating and different artifacts for users to look at. This space was one of the first five-game spaces of the PlayStation Home Open Beta in North America, which Home went Open Beta on December 11.[43] This space was released to the European version on November 5, 2009, almost a year after the Open Beta release. Naughty Dog has also released a game space for Uncharted's sequel on October 23, making Uncharted the first game series to have a game space for both games in its series.[44]

| Aggregator | Score |

|---|---|

| Metacritic | 88/100[45] |

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| 1Up.com | 8.5/10[12] |

| Edge | 8/10[46] |

| Famitsu | 36/40[47] |

| Game Informer | 8.75/10[3] |

| GamePro | 4.25/5[48] |

| GameSpot | 8.0/10[15] |

| GameSpy | 4.5/5[14] |

| IGN | 9.1/10[13] |

| PlayStation: The Official Magazine | |

| PlayStation Universe | 9.0/10[50] |

| Publication | Award |

|---|---|

| IGN | Best Action Game (2007), PS3 Game of the Year (2007), Best Graphics Technology (PS3 2007), Best Original Score (PS3 2007)[51] |

Uncharted: Drake's Fortune received generally favorable reviews from game critics.[45] Game Informer complimented the visuals and dialogue between the characters Drake and Fisher, calling them stunning and entertaining respectively.[28] They further added that the production values appeared high, citing the level of detail and musical score.[52] PlayStation Magazine echoed similar statements about the visuals and compared them to that of Crysis.[18][53]

The overall presentation of the game received unanimous praise from critics, who recognized the game's high production values, describing them as "top-notch",[54] "incredible"[15] or comparing them to those found in Hollywood.[14] When combined with the overall style of the game, this led many reviewers to compare Uncharted to summer blockbuster films,[3][55][56] with the action and theme of the game drawing comparisons to the Indiana Jones film series and Tomb Raider.[15][55] As part of the presentation, the game's story and atmosphere were also received well.[3][55] The depth of the characters was praised, each having "their own tone".[55] The voice acting was also received well, as the cast "nails its characterizations"; overall, the voice acting was described as a "big-star performance",[14] "superb"[56] and "stellar".[3] Game designer Tim Schafer, well known as the creator of the early LucasArts adventure games such as The Secret of Monkey Island, has also lauded the game, saying he "liked it a lot", and jokingly thanked it for teaching him a new fashion tip (Nathan Drake's "half-tucked" shirt).[57]

The technical achievements in creating this presentation were also lauded. The graphics and visuals were a big part of this, including appreciation of the "lush" jungle environments,[3][12][15] with lighting effects greatly adding to them.[56] The game's water effects were also appreciated.[54] Overall, many reviewers commented that, at the time, it was one of the best-looking PlayStation 3 games available.[48] Further to the graphical aspects, both facial animation and the animation of characters,[16][56] such as Nate's "fluid" animations as he performs platforming sections were noted,[3] although the wilder animations of enemies reacting to being shot were over-animated "to perhaps a laug

Ultimate Black theme by mickeyknox

Download: UltimateBlack.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

P3T Unpacker v0.12

Copyright (c) 2007. Anoop Menon

This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit!

Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip

Instructions:

Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme.

The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract.

The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename].

For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following:

p3textractor filename.p3t [destination path]Replace filename with the name of the p3t file, and replace [destination path] with the name of the folder you want the files to be extracted to. A destination path is not required. By default it will extract to extracted.filename.

TOOL theme by TTownEP

Download: Tool_2.p3t

(3 background)

Redirect to:

This page is a redirect. The following categories are used to track and monitor this redirect:

|

This theme by Wingsofbacon

Download: ThisTheme.p3t

(2 backgrounds)

This may refer to:

Domo-Kun theme by KunStraint

Download: DomoKun.p3t

(6 backgrounds)

Redirect to:

Cloud Strife theme by PSPMAN07

Download: CloudStrife.p3t

(2 backgrounds)

| Cloud Strife | |

|---|---|

| Final Fantasy character | |

Cloud Strife artwork by Tetsuya Nomura for Final Fantasy VII. | |

| First game | Final Fantasy VII (1997) |

| Created by | Yoshinori Kitase, Kazushige Nojima, Tetsuya Nomura, Hironobu Sakaguchi |

| Designed by | Tetsuya Nomura |

| Voiced by |

|

| In-universe information | |

| Weapon | Buster Sword |

| Family | Mother - Claudia (Deceased) Father - Unknown |

| Home | Nibelheim |

Cloud Strife (Japanese: クラウド・ストライフ, Hepburn: Kuraudo Sutoraifu) is the protagonist of Square Enix's (previously Square's) role-playing video game Final Fantasy VII (1997), Final Fantasy VII Remake (2020), Final Fantasy VII Rebirth (2024) & the animated film Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children (2005). He acts in a supporting role in other Compilation of Final Fantasy VII titles, and is featured in several other games in the wider Final Fantasy series. He has also made guest appearances in various titles outside the franchise, such as the Kingdom Hearts series by Square Enix and Disney and the Super Smash Bros. series by Nintendo.

Cloud was designed by Tetsuya Nomura, a character artist for the Final Fantasy series, whose role expanded during the title's development to include supervision over Cloud's personality. Yoshinori Kitase, director of VII, and Kazushige Nojima, one of the game's events planners, developed the story and wanted to create a mysterious character who acted atypically for a hero. After VII, Nomura redesigned Cloud for Advent Children, giving him a more realistic appearance alongside new weaponry and a new outfit. For Remake, the team aimed to adapt his classic design for a more realistic artstyle.

Cloud has garnered primarily positive reception from critics, and has been described as one of the most iconic video game protagonists. He has also been cited favorably as an example of complex character writing in video games, as one of its first unreliable narrators and for the game's depiction of his mental disorder. Additionally, he is seen as a messiah figure in both the game and film for opposing Sephiroth's schemes and supported by his allies.

In contrast to Final Fantasy VI, which featured multiple "main characters", Square's staff decided in the beginning of Final Fantasy VII's development that the game would follow a single identifiable protagonist.[1] In Hironobu Sakaguchi's first plot treatment, a prototype for Cloud's character belonged to an organization attempting to destroy New York City's "Mako Reactors".[2] Kitase and Nomura discussed that Cloud would be the lead of three protagonists,[3] but Nomura did not receive character profiles or a completed scenario in advance.[4] Left to imagine the stories behind the characters he designed, Nomura shared these details in discussions with staff or in separately penned notes.[4] Frustrated by the continued popularity of Final Fantasy IV's characters despite the release of two sequels, Nomura made it his goal to create a memorable cast.[3] The contrast between Cloud, a "young, passionate boy", and Sephiroth, a "more mature and cool" individual, struck Amano as "intriguing", though not unusual as a pairing.[5] When designing Cloud and Sephiroth, Nomura imagined a rivalry mirroring that of Miyamoto Musashi and Sasaki Kojirō, with Cloud and Sephiroth representing Musashi and Kojirō, respectively.[6]

Kitase and Nojima developed Cloud's backstory and his relationship to Sephiroth.[7] While drafting the game's scenario, Nojima saw a standing animation created by event planner Motomu Toriyama that depicted "Cloud showing off".[4] The animation impressed Nojima and inspired the idea that Cloud had developed a false persona.[4] This later led Nojima to create Zack Fair, a SOLDIER whom Cloud aspired to be like, to expand on the mystery of Cloud's past.[8] Nojima left the unfolding of events regarding Cloud's identity unwritten,[8] and Kitase was unaware of the significance of Zack's addition until playtesting.[4] Kitase reviewed Nojima's scenario and felt that Cloud, who was neither single-minded nor righteous, offered a fresh take on a protagonist.[4] The love triangle between Cloud, Tifa Lockhart, and Aerith Gainsborough was also viewed as novel for the series.[4] Nojima likened Cloud and Tifa's relationship to one of friends since nursery school, and compared Aerith to a transfer student arriving mid-term.[4]

In early scripts, Sephiroth would have deceived Cloud into thinking that he had created him, and he had the ability to exert control over Cloud's movements.[9] As in the finished game, Cloud would discover that Shinra's experiments and his own insecurities had made him susceptible to Sephiroth's manipulation.[9] Cloud would have also somehow injured Tifa prior to the game's events, leaving her with memory loss of the event and a large scar on her back.[10] Kitase rejected a proposed scene written by Masato Kato involving Cloud and Tifa walking out of a Chocobo stable the morning before the final battle, with Tifa following only after checking around.[4] Kitase found it "too intense" and Nojima described the proposal as "extreme"; however, Kitase maintained a toned-down scene written by Kato depicting the night before, which has Tifa speak a risqué line of dialogue before a fade to black.[4] According to Nojima, none of the staff expected that the scene, despite "the line in question", "would be something so important".[4]

Nojima wanted to write scenes in such a way that players themselves could decide what Cloud was thinking.[11] Nojima used Cloud's foggy memories as a device to provide details about the world that would be unknown to the player but considered common knowledge to its inhabitants.[12] To emphasize Cloud's personality, event planners repeated elements they found interesting, such as Toriyama's standing animation and Cloud's use of the phrase "not interested".[4]

In retrospective, Nomura and Final Fantasy VII Remake co-director Naoki Hamaguchi have described Cloud as a "dorky character".[13] According to Nomura, although post-Final Fantasy VII titles featuring Cloud have emphasized his "cool side", "in the original game, Cloud had many comical or lame moments".[14] Nomura believes that the reason Cloud became popular with audiences is due to the impact his personality made on Nojima's scenario.[15]

In addition to testing models ported from Square's 1995 SIGGRAPH demo, Nomura and several other artists created new characters, including an early design of Cloud.[2] Sakaguchi, impressed with Nomura's illustrations and detailed handwritten notes for Final Fantasy V and VI,[16] tasked him with designing Final Fantasy VII's main characters.[17]

Nomura's notes listed Cloud's job as magic swordsman (魔法剣士, mahō kenshi).[10] Cloud's design underwent several revisions.[18] Nomura's first draft of Cloud featured slicked-back black hair to contrast with the long silver hair of the game's primary antagonist, Sephiroth,[19] and to minimize the model's polygon count.[20] However, to make Cloud stand out more and emphasize his role as the game's lead protagonist, Nomura altered Cloud's design to give him spiky, bright blond hair.[21] Nomura also made Cloud taller than he appeared in the SGI Onyx demo,[2] while a discarded iteration drawn "more on the realistic side" depicted Cloud with a taller head and body and more muscular physique.[18]

Yoshitaka Amano, who handled character illustrations for previous Final Fantasy titles, painted promotional images for the game by taking Nomura's "drawings and put[ting his] own spin on them".[22] According to Amano, because of the hardware limitations of the PlayStation, the platform Square had settled on for Final Fantasy VII, characters could not be rendered realistically.[23] Amano thought that Cloud's baggy pants, which taper at the bottom, reflected a "very ... Japanese style", resembling the silhouette of a hakama.[5]

Early renditions of Cloud's weapon, the Buster Sword (バスターソード, Basutā Sōdo), depicted a smaller, thinner blade.[15] Variations included additions such as a small chain connected to the pommel, magnets securing the blade to Cloud's back,[10] and a more detailed design that resembled a "Western-style sword".[18] The Buster Sword's blade grew in subsequent illustrations,[24] and Nomura called it "the Giant Kitchen Knife", envisioning it as unrefined steel.[24] Square's staff conceived of a minigame involving Cloud driving a motorcycle at the start of the game's development,[25] and Nomura's illustrations included Cloud riding a "Hardy-Daytona" (ハーディ=デイトナ, Hādi-Deitona), a Shinra motorcycle based on a real-life motorbike, the Yamaha VMAX.[26]

For Advent Children, Nomura agreed to direct the project largely because of his attachment to Cloud's character.[27] Although Nomura stated that Cloud was a more positive character in Final Fantasy VII than in Advent Children, he did not believe that such an "'upbeat' image of him is what stuck in the minds of the fans", and the script was written to explain why Cloud returned to a state of mind "consistent with the fans' view of him".[28] Nomura describes Cloud's life as peaceful but, hurt by the losses he experienced during the original game, one which he grew scared of losing.[29] Blaming himself for things outside of his control, Cloud, Nomura elaborated, needed to overcome himself.[30] In contrast to other heroes, who Nomura sees as typically possessing character defects amounting only to quirks, he believed Cloud's weakness to be humanizing.[31]

Nojima viewed the theme of the story as one of forgiveness, which he believed required hardship; by taking up his sword and fighting, Cloud struggles to achieve it.[32] Nojima sought to establish Cloud's withdrawn personality by depicting him as having a cell phone, but never answering any calls. He originally intended for Aerith's name to be the last one displayed in the backlog of ignored messages that appear as Cloud's cell phone sinks into the water, but altered the scene because it "sounded too creepy".[33] The wolf which Cloud imagines "represents the deepest part of Cloud's psyche" and "appears in response to some burden that Cloud is carrying deep in his heart",[34] vanishing at the film's end. Nomura cites one of the film's final scenes, in which Cloud smiles, as his favorite, highlighting the lack of dialogue and Cloud's embarrassment.[35] The scene influenced composer Nobuo Uematsu's score, who grew excited after coming across it in his review of the script, commenting on the difficulty players who had finished Final Fantasy VII would have had imagining Cloud's smile.[35]

Nomura sought to make Cloud's design distinctly different from the other characters.[24] About thirty different designs were made for Cloud's face, and his hair was altered to give it a more realistic look and illustrate that two years had passed since the game's conclusion.[36] The staff attempted rendering Cloud based on the game's original illustrations, but concluded that doing so left his eyes unrealistically big, which "looked gross".[37] Further revisions were made to Cloud's face after completion of the pilot film, which featured a more realistic style.[38] In contrast to his hair, Cloud's clothes were difficult to make in the film.[39] After deciding to give Cloud a simple costume consistent with the concept of "clothes designed for action", the staff began with the idea of a black robe, eventually parring it down to a "long apron" shifted to one side.[36]

Cloud's weaponry was based on the joking observation that because his sword in the original game was already enormously tall, in the sequel, he should use sheer numbers.[40] Referred to as "The Fusion Swords" (合体剣, Gattai Ken) during the film's development,[41] early storyboard concepts included Cloud carrying six swords on his back,[40] although the idea was later modified to six interlocking swords. While the idea wasn't "logically thought out" and the staff did not think that they could "make it work physically", it was believed to provide "an interesting accent to the story".[42] Cloud's new motorcycle, Fenrir (フェンリル, Fenriru), was designed by Takayuki Takeya, who was asked by the staff to design an upgraded version of Cloud's "Hardy-Daytona" motorcycle from Final Fantasy VII. The bike got bigger as development continued, with Takeya feeling its heaviness provided an impact that worked well within the film.[43] In the original game, Cloud's strongest technique was the Omnislash (超究武神覇斬, Choukyūbushinhazan, lit. "Super-ultimate War-god Commanding Slash"). For his fight against Sephiroth in the film, Nomura proposed a new move, the Omnislash Ver. 5 (超究武神覇斬ver.5, Choukyūbushinhazan ver.5), a faster version of the original Omnislash. The staff laughed at the name of Cloud's move during the making of it, as Nomura was inspired by a sports move from Final Fantasy X, whose protagonist, Tidus, explained the addition of a more specific name would make people more excited.[44]

Themes expanded upon in the director's cut Advent Children Complete include Cloud's development with links to other Final Fantasy VII media in which he appeared.[45] To further focus on Cloud's growth, Square decided to give him more scenes when he interacts with children. Additionally, the fight between Cloud and Sephiroth was expanded by several minutes, and includes a scene in which Sephiroth impales Cloud on his sword and holds him in the air, mirroring the scene in the game where he performs the same action. The decision to feature Cloud suffering from blood loss in the fight was made in order to make his pain feel realistic.[46]

In the making of the fighting game Dissidia: Final Fantasy, Nomura stated that Cloud's appearance was slightly slimmer than in Final Fantasy VII because of the detail the 3D of the PlayStation Portable could give him. While also retaining his original design and his Advent Children appearance, Cloud was given a more distinct look based on his Final Fantasy VII persona.[47]

Cloud's initial redesign for Final Fantasy VII Remake was initially more different than the original, but was later altered to more closely resemble Nomura's original design.[13] Early on in Final Fantasy VII, Cloud crossdresses in order to find Tifa, and Nomura noted this event was popular with the fans and reassured that the remake would keep this part. On the other hand, the character designer stated that their final design was not decided yet.[48] Kazushige Nojima worked on making Cloud's interactions with Tifa and Barret natural. Despite fear of the possible result, Nojima also wanted players to connect with the character once again.[49] Kitase further claimed that in the remake they aimed to make Cloud more inexperienced and informal than in Advent Children, due to him not being fully mature.[50]

Co-director Naoki Hamaguchi noted that since the original game offered the option for the player to decide Cloud's interest in a female character, he wanted the remake to retain this in the form of an intimate conversation when splitting from the main team.[51] The theme song "Hollow" is meant to reflect Cloud's state of mind, with Nomura placing high emphasis on the rock music and male vocals.[52]

The original Final Fantasy VII did not have voice acting. For the Ehrgeiz fighting game, Kenyu Horiuchi voiced Cloud in the arcade version and Nozomu Sasaki voiced him in the home console version.[53] Since Kingdom Hearts, Takahiro Sakurai has been the Japanese voice of Cloud, with Teruaki Sugawara, the voice director at Square, recommending him to Nomura based on prior experience.[54] Nomura had originally asked Sakurai to play the protagonist of The Bouncer, Sion Barzahd, but found that his voice best suited Cloud after hearing him speak.[54] Sakurai received the script without any accompanying visuals, and first arrived for recording under the impression that he would be voicing a character other than Cloud.[55] For Advent Children, Nomura wanted to contrast Cloud and Vincent's voices because of their similar personalities.[56] As a sequel to the highly popular Final Fantasy VII, Sakurai felt greater pressure performing the role than he did when he voiced Cloud for Kingdom Hearts. Sakurai received comments from colleagues revealing their love of the game, some of them jokingly threatening that they would not forgive him if he did not meet their expectations.[55]

During recording, Sakurai was told that "[n]o matter what kind of odds are stacked against him, Cloud won't be shaken".[57] Sakurai says that while he recorded most of his work individually, he performed alongside Ayumi Ito, who voiced Tifa, for a few scenes. These recordings left him feeling "deflated", as the "exchanges he has with Tifa can be pretty painful", with Sakurai commenting that Cloud—whom he empathized with as his voice actor—has a hard time dealing with straight talk.[58] Sakurai says that there were scenes that took over a year to complete, with very precise directions being given requiring multiple takes.[59]

According to Sakurai, Cloud's silence conveys more about him than when he speaks. While possessing heroic characteristics, Sakurai describes Cloud's outlook as negative, and says that he is delicate in some respects.[55] A fan of VII, Sakurai had believed Cloud to be a colder character based on his original impression of him, but later came to view him as more sentimental.[54] After the final product was released, Sakurai was anxious to hear the fans' response, whether positive or negative, and says that most of the feedback he received praised him.[55] While recording Crisis Core, Sakurai felt that Cloud, though still introverted, acted more like a normal teenager, and modified his approach accordingly. Cloud's scream over Zack's death left a major impression on Sakurai, who says that he worked hard to convey the emotional tone of the ending.[55] Sakurai has come to regard Cloud as an important role, commenting that Cloud reminds him of his own past, and that, as a Final Fantasy VII fan himself, he is happy to contribute.[55]

For the remake of Final Fantasy VII, Sakurai found Cloud more difficult to portray than his previous performances. He re-recorded his lines multiple times, and credited the voice director with guiding him.[60] Nomura elaborated that the remake's interpretation of Cloud has a distinct personality; he attempts to act cool, but often fails to do so and instead comes across as awkward, which Nomura asked Sakurai to reflect in his acting. Another challenge for the developers was finding a suitable voice for the teenage Cloud seen during flashbacks. In order to better match Cloud's rural upbringing, they decided to hire a child from a rural area rather than an established actor, and ultimately went with 13-year-old Yukihiro Aizawa.[61][62]

In most English adaptations, Cloud is voiced by Steve Burton, who was first hired to voice Cloud after a Square employee saw his role in the 2001 film The Last Castle.[63] Burton's work as Cloud in Advent Children served as his first feature-length role, an experience he enjoyed.[64] Calling the character a rare opportunity for him as an actor, Burton describes Cloud as having a "heaviness about him".[65] Burton says he is surprised when fans recognize him for his work as Cloud, whom he has referred to as "[one of the] coolest characters there is", and considers himself lucky to have voiced him.[64]

Although Burton expressed his desire to voice Cloud for the remake of Final Fantasy VII, he was replaced by Cody Christian; Burton thanked Square for his work, and wished Christian luck.[66][67] Christian said that he was honored to portray what he described as an iconic character, and vowed to give his best performance.[68] He also commented on Burton's previous work, stating, "Steve, you paved the way. You made this character what it is and have contributed in shaping a legacy".[69] Christian used Burton's works as an inspiration for his portrayal of the character.[70] Teenage Cloud was voiced in English by Major Dodson.[71] For the next installment, Christian said that that the character differed from Remake as he aimed to explore more his sensitive side like his past or intimate relationships he is often involved.[72]

Cloud is introduced as a mercenary employed by AVALANCHE, an eco-terrorist group opposed to the Shinra Company, and who claims to be formerly of SOLDIER 1st Class, an elite Shinra fighting unit.[73] Beginning the game with the placeholder name "Ex-SOLDIER" (元ソルジャー, Moto Sorujā), Cloud assists AVALANCHE's leader, Barret Wallace, in bombing a Mako reactor, power plants which drain the planet's "Lifestream". Despite appearing detached [74] and more interested in the pay of his work, Cloud demonstrates moments of camaraderie, such as prioritizing Jesse's security over his escape during the Mako Reactor 1's explosion.[75] Players can choose to interact in a friendlier manner with AVALANCHE's members.[76] After being approached by his childhood friend and AVALANCHE member, Tifa Lockhart,[77] Cloud agrees to continue helping AVALANCHE.[78][79] Cloud encounters Aerith Gainsborough, a resident of Midgar's slums, and agrees to serve as her bodyguard in exchange for a date.[80] He helps her evade Shinra, who are pursuing her because she is the sole survivor of a race known as the Cetra. During the course of their travels, a love triangle develops between Cloud, Tifa and Aerith.[81][82]

Following the player's departure from Midgar, Cloud narrates his history with Sephiroth, a legendary member of SOLDIER and the game's primary antagonist, and the events that led to his disappearance five years prior. Cloud joined SOLDIER to emulate Sephiroth, and explains that he would sign up for a "big mission" whenever they became available, as the conclusion of Shinra's war with the people of Wutai ended his chances for military fame.[83] Sephiroth started questioning his humanity after accompanying him on a job to Cloud's hometown of Nibelheim and discovering documents concerning Jenova, an extraterrestrial lifeform and Sephiroth's "mother".[84] This ultimately led to Sephiroth burning down Nibelheim. Cloud confronted Sephiroth at Mt Nibel's Mako Reactor and was believed to have killed him, but Cloud dismisses this as a lie, as he knows he would be no match for Sephiroth. He is troubled with the fact that although he most likely would have lost the fight, he lived after challenging Sephiroth.

However, numerous visual and audio clues suggest the unreliability of Cloud's memory. Cloud will spontaneously remember words or scenes from his past, sometimes collapsing to the ground while cradling his head,[85] and appears not to remember things that he should, such as the existence of a SOLDIER First Class named Zack.[86] As Sephiroth begins manipulating his mind,[87] he takes advantage of his memory by telling him that his past is merely fiction and that Shinra created him in an attempt to clone Sephiroth.[88] Cloud learns he cannot remember things such as how or when he joined SOLDIER and resigns himself as a "failed experiment",[89] then goes missing. The party later discovers a comatose Cloud suffering from Mako poisoning.

It is revealed that Cloud never qualified for SOLDIER, and instead enlisted as an infantryman in Shinra's army. During the mission to Nibelheim, he served under Sephiroth and Zack and hid his identity from the townspeople out of embarrassment. Following Sephiroth's defeat of Zack at the Mt. Nibel Mako reactor, Cloud managed to ambush him and throw him into the Lifestream, and believed him to be dead. Both he and Zack were then imprisoned by Shinra's lead scientist, Hojo, for experimentation. Zack later escaped with Cloud to the outskirts of Midgar before Shinra soldiers gunned him down. As a result of exposure to Mako radiation and the injection of Jenova's cells,[90] Cloud's mind created a false personality largely based on Zack's, inadvertently erasing the latter from his memory.[91] After piecing together his identity, Cloud resumes his role as leader and silently expresses his mutual feelings with Tifa the night before the final battle. At the game's conclusion, Sephiroth reappears in Cloud's mind a final time, but is defeated in a one-on-one fight.[92]

Cloud appears in a minor role in the mobile game Before Crisis, a prequel set six years before the events of Final Fantasy VII. The player, a member of the Shinra covert operatives group, the Turks, encounters Cloud during his time as a Shinra infantryman working to join SOLDIER. The game portrays Cloud's natural talent for swordsmanship,[93] and recounts his role during Nibelheim's destruction.

In the 2005 animated film Advent Children, which is set two years after the conclusion of Final Fantasy VII,[94] Cloud lives with Tifa in the city of Edge along with Marlene, Barret's adopted daughter, and Denzel, an orphan affected by a rampant and deadly disease called Geostigma. Having given up his life as a mercenary,[95] Cloud now works as a courier for the "Strife Delivery Service" (ストライフ・デリバリーサービス, Sutoraifu Deribarī Sābisu), which Tifa set up in her new bar. After Tifa confronts him following the disappearance of Denzel and Marlene, it is revealed that he also suffers from the effects of Geostigma, and he responds that he is unfit to protect his friends and new family.[96]

However, after Tifa urges him to let go of the past,[97] Cloud sets out for the Forgotten City in search of the children. There, he confronts Kadaj, Loz, and Yazoo, genetic remnants of Sephiroth left behind before he diffused into the Lifestream completely.[98] Cloud's battle with Kadaj takes them back to Aerith's church, where Cloud recovers from his Geostigma with Aerith's help.[99] After merging with the remains of Jenova, Kadaj, resurrects Sephiroth. Cloud, having overcome his doubts, defeats Sephiroth once more, leaving a dying Kadaj in his place.[100] At the film's conclusion, Cloud, seeing Aerith and Zack, assures them that he will be fine and reunites with his friends.

Cloud appears in On the Way to a Smile, a series of short stories set between Final Fantasy VII and Advent Children. "Case of Tifa" serves as an epilogue to VII, and portrays Cloud's life alongside Tifa, Marlene, and Denzel. "Case of Denzel" relates how Cloud first met Denzel,[101] and was later adapted as a short original video animation for the release of Advent Children Complete, On the Way to a Smile - Episode: Denzel.[102]

Cloud appears in a supporting role in the PlayStation 2 game Dirge of Cerberus. A year after the events of Advent Children,[103] Cloud, working alongside Barret and Tifa, lends his support to the ground forces of the

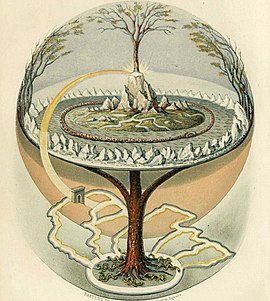

World theme by Harry

Download: World.p3t

(1 background)

The world is the totality of entities, the whole of reality, or everything that exists.[1] The nature of the world has been conceptualized differently in different fields. Some conceptions see the world as unique while others talk of a "plurality of worlds". Some treat the world as one simple object while others analyze the world as a complex made up of parts.

In scientific cosmology, the world or universe is commonly defined as "[t]he totality of all space and time; all that is, has been, and will be". Theories of modality talk of possible worlds as complete and consistent ways how things could have been. Phenomenology, starting from the horizon of co-given objects present in the periphery of every experience, defines the world as the biggest horizon or the "horizon of all horizons". In philosophy of mind, the world is contrasted with the mind as that which is represented by the mind. Theology conceptualizes the world in relation to God, for example, as God's creation, as identical to God or as the two being interdependent. In religions, there is a tendency to downgrade the material or sensory world in favor of a spiritual world to be sought through religious practice. A comprehensive representation of the world and our place in it, as is found in religions, is known as a worldview. Cosmogony is the field that studies the origin or creation of the world while eschatology refers to the science or doctrine of the last things or of the end of the world.

In various contexts, the term "world" takes a more restricted meaning associated, for example, with the Earth and all life on it, with humanity as a whole or with an international or intercontinental scope. In this sense, world history refers to the history of humanity as a whole and world politics is the discipline of political science studying issues that transcend nations and continents. Other examples include terms such as "world religion", "world language", "world government", "world war", "world population", "world economy", or "world championship".

The English word world comes from the Old English weorold. The Old English is a reflex of the Common Germanic *weraldiz, a compound of weraz 'man' and aldiz 'age', thus literally meaning roughly 'age of man';[2] this word led to Old Frisian warld, Old Saxon werold, Old Dutch werolt, Old High German weralt, and Old Norse verǫld.[3]

The corresponding word in Latin is mundus, literally 'clean, elegant', itself a loan translation of Greek cosmos 'orderly arrangement'. While the Germanic word thus reflects a mythological notion of a "domain of Man" (compare Midgard), presumably as opposed to the divine sphere on the one hand and the chthonic sphere of the underworld on the other, the Greco-Latin term expresses a notion of creation as an act of establishing order out of chaos.[4]

Different fields often work with quite different conceptions of the essential features associated with the term "world".[5][6] Some conceptions see the world as unique: there can be no more than one world. Others talk of a "plurality of worlds".[4] Some see worlds as complex things composed of many substances as their parts while others hold that worlds are simple in the sense that there is only one substance: the world as a whole.[7] Some characterize worlds in terms of objective spacetime while others define them relative to the horizon present in each experience. These different characterizations are not always exclusive: it may be possible to combine some without leading to a contradiction. Most of them agree that worlds are unified totalities.[5][6]