Watchmen theme by Proinsias

Download: Watchmen.p3t

(13 backgrounds)

| Watchmen | |

|---|---|

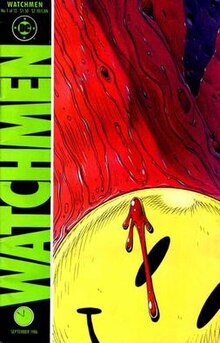

Cover of Watchmen #1 (September 1986) Art by Dave Gibbons | |

| Date | 1986–1987 |

| Publisher | DC Comics |

| Creative team | |

| Writer | Alan Moore |

| Artist | Dave Gibbons |

| Colorist | John Higgins |

| Editors | |

| Original publication | |

| Published in | Watchmen |

| Issues | 12 |

| Date of publication | September 1986 – October 1987 |

Watchmen is a comic book limited series by the British creative team of writer Alan Moore, artist Dave Gibbons and colorist John Higgins. It was published monthly by DC Comics in 1986 and 1987 before being collected in a single-volume edition in 1987. Watchmen originated from a story proposal Moore submitted to DC featuring superhero characters that the company had acquired from Charlton Comics. As Moore's proposed story would have left many of the characters unusable for future stories, managing editor Dick Giordano convinced Moore to create original characters instead.

Moore used the story as a means of reflecting contemporary anxieties, of deconstructing and satirizing the superhero concept and of making political commentary. Watchmen depicts an alternate history in which superheroes emerged in the 1940s and 1960s and their presence changed history so that the United States won the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal was never exposed. In 1985 the country is edging toward World War III with the Soviet Union, freelance costumed vigilantes have been outlawed and most former superheroes are in retirement or working for the government. The story focuses on the protagonists' personal development and moral struggles as an investigation into the murder of a government-sponsored superhero pulls them out of retirement.

Gibbons uses a nine-panel grid layout throughout the series and adds recurring symbols such as a blood-stained smiley face. All but the last issue feature supplemental fictional documents that add to the series' backstory and the narrative is intertwined with that of another story, an in-story pirate comic titled Tales of the Black Freighter, which one of the characters reads. Structured at times as a nonlinear narrative, the story skips through space, time and plot. In the same manner, entire scenes and dialogues have parallels with others through synchronicity, coincidence, and repeated imagery.

A commercial success, Watchmen has received critical acclaim both in the comics and mainstream press. Watchmen was recognized in Time's List of the 100 Best Novels as one of the best English language novels published since 1923. In a retrospective review, the BBC's Nicholas Barber described it as "the moment comic books grew up".[1] Moore opposed this idea, stating, "I tend to think that, no, comics hadn't grown up. There were a few titles that were more adult than people were used to. But the majority of comics titles were pretty much the same as they'd ever been. It wasn't comics growing up. I think it was more comics meeting the emotional age of the audience coming the other way."[2]

After a number of attempts to adapt the series into a feature film, director Zack Snyder's Watchmen was released in 2009. A video game series, Watchmen: The End Is Nigh, was released to coincide with the film's release.

DC Comics published Before Watchmen, a series of nine prequel miniseries, in 2012, and Doomsday Clock, a 12-issue limited series and sequel to the original Watchmen series, from 2017 to 2019 – both without Moore's or Gibbons' involvement. The second series integrated the Watchmen characters within the DC Universe. A standalone sequel, Rorschach by Tom King, began publication in October 2020. A television continuation to the original comic, set 34 years after the comic's timeline, was broadcast on HBO from October to December 2019 with Gibbons' involvement. Moore has expressed his displeasure with adaptations and sequels of Watchmen and asked it not be used for future works.[3]

Publication history[edit]

Watchmen, created by writer Alan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons, first appeared in the 1985 issue of DC Spotlight, the 50th anniversary special. It was eventually published as a 12-issue maxiseries from DC Comics, cover-dated September 1986 to October 1987.[4]

| No. | Title | Publication date | On-sale date | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1

|

"At Midnight, All the Agents..." | September 1986 | May 13, 1986 | |

2

|

"Absent Friends" | October 1986 | June 10, 1986 | |

3

|

"The Judge of All the Earth" | November 1986 | July 8, 1986 | |

4

|

"Watchmaker" | December 1986 | August 12, 1986 | |

5

|

"Fearful Symmetry" | January 1987 | September 9, 1986 | |

6

|

"The Abyss Gazes Also" | February 1987 | October 14, 1986 | |

7

|

"A Brother to Dragons" | March 1987 | November 11, 1986 | |

8

|

"Old Ghosts" | April 1987 | December 9, 1986 | |

9

|

"The Darkness of Mere Being" | May 1987 | January 13, 1987 | |

10

|

"Two Riders Were Approaching..." | July 1987 | March 17, 1987 | |

11

|

"Look on My Works, Ye Mighty..." | August 1987 | May 19, 1987 | |

12

|

"A Stronger Loving World" | October 1987 | July 28, 1987 |

It was subsequently collected in 1987 as a DC Comics trade paperback that has had at least 24 printings as of March 2017;[17] another trade paperback was published by Warner Books, a DC sister company, in 1987.[18] In February 1988, DC published a limited-edition, slipcased hardcover volume, produced by Graphitti Design, that contained 48 pages of bonus material, including the original proposal and concept art.[19][20] In 2005, DC released Absolute Watchmen, an oversized slipcased hardcover edition of the series in DC's Absolute Edition format. Assembled under the supervision of Dave Gibbons, Absolute Watchmen included the Graphitti materials, as well as restored and recolored art by John Higgins.[21] That December DC published a new printing of Watchmen issue #1 at the original 1986 cover price of $1.50 as part of its "Millennium Edition" line.[22]

In 2012, DC published Before Watchmen, a series of nine prequel miniseries, with various creative teams producing the characters' early adventures set before the events of the original series.[23]

In the 2016 one-shot DC Universe: Rebirth Special, numerous symbols and visual references to Watchmen, such as the blood-splattered smiley face, and the dialogue between Doctor Manhattan and Ozymandias in the last issue of Watchmen, are shown.[24] Further Watchmen imagery was added in the DC Universe: Rebirth Special #1 second printing, which featured an update to Gary Frank's cover, better revealing the outstretched hand of Doctor Manhattan in the top right corner.[25][26] Doctor Manhattan later appeared in the 2017 four-part DC miniseries The Button serving as a direct sequel to both DC Universe Rebirth and the 2011 storyline "Flashpoint". Manhattan reappears in the 2017–19 twelve-part sequel series Doomsday Clock.[27]

Background and creation[edit]

"I suppose I was just thinking, 'That'd be a good way to start a comic book: have a famous super-hero found dead.' As the mystery unraveled, we would be led deeper and deeper into the real heart of this super-hero's world, and show a reality that was very different to the general public image of the super-hero."

—Alan Moore on the basis for Watchmen[28]

In 1983, DC Comics acquired a line of characters from Charlton Comics.[29] During that period, writer Alan Moore contemplated writing a story that featured an unused line of superheroes that he could revamp, as he had done in his Miracleman series in the early 1980s. Moore reasoned that MLJ Comics' Mighty Crusaders might be available for such a project, so he devised a murder mystery plot which would begin with the discovery of the body of the Shield in a harbor. The writer felt it did not matter which set of characters he ultimately used, as long as readers recognized them "so it would have the shock and surprise value when you saw what the reality of these characters was".[28] Moore used this premise and crafted a proposal featuring the Charlton characters titled Who Killed the Peacemaker,[30] and submitted the unsolicited proposal to DC managing editor Dick Giordano.[31] Giordano was receptive to the proposal, but opposed the idea of using the Charlton characters for the story. After the acquisition of Charlton's Action Hero line, DC intended to use their upcoming Crisis on Infinite Earths event to fold them into their mainstream superhero universe. Moore said, "DC realized their expensive characters would end up either dead or dysfunctional." Instead, Giordano persuaded Moore to continue his project but with new characters that simply resembled the Charlton heroes.[32][33][34] Moore had initially believed that original characters would not provide emotional resonance for readers but later changed his mind. He said, "Eventually, I realized that if I wrote the substitute characters well enough, so that they seemed familiar in certain ways, certain aspects of them brought back a kind of generic super-hero resonance or familiarity to the reader, then it might work."[28]

Artist Dave Gibbons, who had collaborated with Moore on previous projects, recalled that he "must have heard on the grapevine that he was doing a treatment for a new miniseries. I rang Alan up, saying I'd like to be involved with what he was doing", and Moore sent him the story outline.[35] Gibbons told Giordano he wanted to draw the series Moore proposed and Moore approved.[36] Gibbons brought colorist John Higgins onto the project because he liked his "unusual" style; Higgins lived near the artist, which allowed the two to "discuss [the art] and have some kind of human contact rather than just sending it across the ocean".[30] Len Wein joined the project as its editor, while Giordano stayed on to oversee it. Both Wein and Giordano stood back and "got out of their way", as Giordano remarked later. "Who copy-edits Alan Moore, for God's sake?"[31]

After receiving the go-ahead to work on the project, Moore and Gibbons spent a day at the latter's house creating characters, crafting details for the story's milieu and discussing influences. The pair were particularly influenced by a Mad parody of Superman named "Superduperman"; Moore said: "We wanted to take Superduperman 180 degrees—dramatic, instead of comedic".[34] Moore and Gibbons conceived of a story that would take "familiar old-fashioned superheroes into a completely new realm";[37] Moore said his intention was to create "a superhero Moby Dick; something that had that sort of weight, that sort of density".[38] Moore came up with the character names and descriptions but left the specifics of how they looked to Gibbons. Gibbons did not sit down and design the characters deliberately, but rather "did it at odd times [...] spend[ing] maybe two or three weeks just doing sketches."[30] Gibbons designed his characters to make them easy to draw; Rorschach was his favorite to draw because "you just have to draw a hat. If you can draw a hat, then you've drawn Rorschach, you just draw kind of a shape for his face and put some black blobs on it and you're done."[39]

Moore began writing the series very early on, hoping to avoid publication delays such as those faced by the DC limited series Camelot 3000.[40] When writing the script for the first issue Moore said he realized "I only had enough plot for six issues. We were contracted for 12!" His solution was to alternate issues that dealt with the overall plot of the series with origin issues for the characters.[41] Moore wrote very detailed scripts for Gibbons to work from. Gibbons recalled that "[t]he script for the first issue of Watchmen was, I think, 101 pages of typescript—single-spaced—with no gaps between the individual panel descriptions or, indeed, even between the pages." Upon receiving the scripts, the artist had to number each page "in case I drop them on the floor, because it would take me two days to put them back in the right order", and used a highlighter pen to single out lettering and shot descriptions; he remarked, "It takes quite a bit of organizing before you can actually put pen to paper."[42] Despite Moore's detailed scripts, his panel descriptions would often end with the note "If that doesn't work for you, do what works best"; Gibbons nevertheless worked to Moore's instructions.[43] In fact, Gibbons only suggested one single change to the script - a compression of Ozymandias' narration while he was preventing a sneak attack by Rorschach - as he felt that the dialogue was too long to fit with the length of the action; Moore agreed and re-wrote the scene.[44] Gibbons had a great deal of autonomy in developing the visual look of Watchmen and frequently inserted background details that Moore admitted he did not notice until later.[38] Moore occasionally contacted fellow comics writer Neil Gaiman for answers to research questions and for quotes to include in issues.[41]

Despite his intentions, Moore admitted in November 1986 that there were likely to be delays, stating that he was, with issue five on the stands, still writing issue nine.[42] Gibbons mentioned that a major factor in the delays was the "piecemeal way" in which he received Moore's scripts. Gibbons said the team's pace slowed around the fourth issue; from that point onward the two undertook their work "just several pages at a time. I'll get three pages of script from Alan and draw it and then toward the end, call him up and say, 'Feed me!' And he'll send another two or three pages or maybe one page or sometimes six pages."[45] As the creators began to hit deadlines, Moore would hire a taxi driver to drive 50 miles and deliver scripts to Gibbons. On later issues the artist even had his wife and son draw panel grids on pages to help save time.[41]

Near the end of the project, Moore realized that the story bore some similarity to "The Architects of Fear", an episode of The Outer Limits television series.[41] The writer and Wein (an editor) argued over changing the ending and when Moore refused to give in, Wein quit the book. Wein explained, "I kept telling him, 'Be more original, Alan, you've got the capability, do something different, not something that's already been done!' And he didn't seem to care enough to do that."[46] Moore acknowledged the Outer Limits episode by referencing it in the series' last issue.[43]

Synopsis[edit]

Setting[edit]

Watchmen is set in an alternate reality that closely mirrors the contemporary world of the 1980s. The primary difference is the presence of superheroes. The point of divergence occurs in the year 1938. Their existence in this version of the United States is shown to have dramatically affected and altered the outcomes of real-world events such as the Vietnam War and the presidency of Richard Nixon.[47] In keeping with the realism of the series, although the costumed crimefighters of Watchmen are commonly called "superheroes", only one, named Doctor Manhattan, possesses any superhuman abilities.[48] The war in Vietnam ends with an American victory in 1971 and Nixon is still president as of October 1985 upon the repeal of term limits and the Watergate scandal not coming to pass. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan occurs approximately six years later than in real life.

When the story begins, the existence of Doctor Manhattan has given the U.S. a strategic advantage over the Soviet Union, which has dramatically increased Cold War tensions. Eventually, by 1977, superheroes grow unpopular among the police and the public, leading them to be outlawed with the passage of the Keene Act. While many of the heroes retired, Doctor Manhattan and another superhero, known as The Comedian, operate as government-sanctioned agents. Another named Rorschach continues to operate outside the law.[49]

Plot[edit]

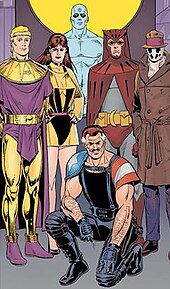

In October 1985, New York City detectives investigate the murder of Edward Blake. With the police having no leads, costumed vigilante Rorschach decides to probe further. Rorschach deduces Blake to have been the true identity of "The Comedian", a costumed hero employed by the U.S. government, after finding his costume and signature smiley-face pin badge. Believing that Blake's murder could be part of a larger plot against costumed adventurers, Rorschach seeks out and warns four of his retired comrades: shy inventor Daniel Dreiberg, formerly the second Nite Owl; the superpowered and emotionally detached Jon Osterman, codenamed "Doctor Manhattan"; Doctor Manhattan's lover Laurie Juspeczyk, the second Silk Spectre; and Adrian Veidt, once the hero "Ozymandias", and now a successful businessman.

Dreiberg, Veidt, and Manhattan attend Blake's funeral, where Dreiberg tosses Blake's pin badge in his coffin before he is buried. Manhattan is later accused on national television of being the cause of cancer in friends and former colleagues. When the government takes the accusations seriously, Manhattan exiles himself to Mars. As the United States depends on Manhattan as a strategic military asset, his departure throws humanity into political turmoil, with the Soviets invading Afghanistan to capitalize on the United States' perceived weakness. Rorschach's concerns appear validated when Veidt narrowly survives an assassination attempt. Rorschach himself is framed for murdering a former supervillain named Moloch. While attempting to flee the scene of Moloch's murder, Rorschach is captured by police and unmasked as Walter Kovacs.

Neglected in her relationship with the once-human Manhattan, whose godlike powers have left him emotionally detached from ordinary people, and no longer kept on retainer by the government, Juspeczyk stays with Dreiberg. They begin a romance, don their costumes, and resume vigilante work as they grow closer together. With Dreiberg starting to believe some aspects of Rorschach's conspiracy theory, the pair take it upon themselves to break him out of prison. After looking back on his own personal history, Manhattan places the fate of his involvement with human affairs in Juspeczyk's hands. He teleports her to Mars to make the case for emotional investment. During the course of the argument, Juspeczyk is forced to come to terms with the fact that Blake, who once attempted to rape her mother (the original Silk Spectre), was actually her biological father, having fathered her in a second, consensual relationship. This discovery, reflecting the complexity of human emotions and relationships, reignites Manhattan's interest in humanity.

On Earth, Dreiberg and Rorschach find evidence that Veidt may be behind the conspiracy. Rorschach writes his suspicions about Veidt in his journal, which includes the full details of his investigation, and mails it to New Frontiersman, a local right-wing newspaper. When Rorschach and Dreiberg travel to Antarctica to confront Veidt at his private retreat, Veidt explains that he plans to save humanity from an impending nuclear war by staging a fake alien invasion and killing half the population of New York, forcing the United States and the Soviet Union to unite against a common enemy. He reveals that he murdered Blake after he discovered his plan, arranged for Doctor Manhattan's past associates to contract cancer to force him to leave Earth, staged the attempt on his own life to place himself above suspicion, and framed Rorschach for Moloch's murder to prevent him from discovering the truth. Horrified by Veidt's callous logic, Dreiberg and Rorschach vow to stop him, but Veidt reveals that he already enacted his plan before they arrived.

When Manhattan and Juspeczyk arrive back on Earth, they are confronted by mass destruction and death in New York, with a gigantic squid-like creature, created by Veidt's laboratories, dead in the middle of the city. Manhattan notices his prescient abilities are limited by tachyons emanating from the Antarctic and the pair teleport there. They discover Veidt's involvement and confront him. Veidt shows everyone news broadcasts confirming that the emergence of a new threat has indeed prompted peaceful co-operation between the superpowers; this leads almost all present to agree that concealing the truth is in the best interests of world peace. Rorschach refuses to compromise and leaves, intent on revealing the truth. As he is making his way back, he is confronted by Manhattan who argues that at this point, the truth can only hurt. Rorschach declares that Manhattan will have to kill him to stop him from exposing Veidt, which Manhattan duly does. Manhattan then wanders through the base and finds Veidt, who asks him if he did the right thing in the end. Manhattan cryptically responds that "nothing ever ends" before leaving Earth. Dreiberg and Juspeczyk go into hiding under new identities and continue their romance.

Back in New York, the editor at New Frontiersman asks his assistant to find some filler material from the "crank file", a collection of rejected submissions to the paper, many of which have not yet been reviewed. The series ends with the young man reaching toward the pile of discarded submissions, near the top of which is Rorschach's journal.

Characters[edit]

With Watchmen, Alan Moore's intention was to create four or five "radically opposing ways" to perceive the world and to give readers of the story the privilege of determining which one was most morally comprehensible. Moore did not believe in the notion of "[cramming] regurgitated morals" down the readers' throats and instead sought to show heroes in an ambivalent light. Moore said, "What we wanted to do was show all of these people, warts and all. Show that even the worst of them had something going for them, and even the best of them had their flaws."[38]

- Adrian Veidt / Ozymandias

- Drawing inspiration from Alexander the Great, Veidt was once the superhero Ozymandias, but has since retired to devote his attention to the running of his own enterprises. Veidt is believed to be the smartest man on the planet. Ozymandias was based on Peter Cannon, Thunderbolt; Moore liked the idea of a character who "us[ed] the full 100% of his brain" and "[had] complete physical and mental control".[28] Richard Reynolds noted that by taking initiative to "help the world", Veidt displays a trait normally attributed to villains in superhero stories, and in a sense he is the "villain" of the series.[50] Gibbons noted, "One of the worst of his sins [is] kind of looking down on the rest of humanity, scorning the rest of humanity."[51]

- Daniel Dreiberg / Nite Owl II

- A retired superhero who utilizes owl-themed gadgets. Nite Owl was based on the Ted Kord version of the Blue Beetle. Paralleling the way Ted Kord had a predecessor, Moore also incorporated an earlier adventurer who used the name "Nite Owl", the retired crime fighter Hollis Mason, into Watchmen.[28] While Moore devised character notes for Gibbons to work from, the artist provided a name and a costume design for Hollis Mason he had created when he was twelve.[52] Richard Reynolds noted in Super Heroes: A Modern Mythology that despite the character's Charlton roots, Nite Owl's modus operandi has more in common with the DC Comics character Batman.[53] According to Klock, his civilian form "visually suggests an impotent, middle-aged Clark Kent."[54]

- Edward Blake / The Comedian

- One of two government-sanctioned heroes (along with Doctor Manhattan) who remains active after the Keene Act is passed in 1977 to ban superheroes. His murder, which occurs shortly before the first chapter begins, sets the plot of Watchmen in motion. The character appears throughout the story in flashbacks and aspects of his personality are revealed by other characters.[49] The Comedian was based on the Charlton Comics character Peacemaker, with elements of the Marvel Comics spy character Nick Fury added. Moore and Gibbons saw The Comedian as "a kind of Gordon Liddy character, only a much bigger, tougher guy".[28] Richard Reynolds described The Comedian as "ruthless, cynical, and nihilistic, and yet capable of deeper insights than the others into the role of the costumed hero."[49]

- Dr. Jon Osterman / Doctor Manhattan

- A superpowered being who is contracted by the United States government. Scientist Jon Osterman gained power over matter when he was caught in an "Intrinsic Field Subtractor" in 1959. Doctor Manhattan was based upon Charlton's Captain Atom, who in Moore's original proposal was surrounded by the shadow of nuclear threat. Captain Atom was the only hero with actual superpowers in Dick Giordano's Action Hero line at Charlton, just like Manhattan is the only character with actual superpowers in Watchmen.[55] However, the writer found he could do more with Manhattan as a "kind of a quantum super-hero" than he could have with Captain Atom.[28] In contrast to other superheroes who lacked scientific exploration of their origins, Moore sought to delve into nuclear physics and quantum physics in constructing the character of Dr. Manhattan. The writer believed that a character living in a quantum universe would not perceive time with a linear perspective, which would influence the character's perception of human affairs. Moore also wanted to avoid creating an emotionless character like Spock from Star Trek, so he sought for Dr. Manhattan to retain "human habits" and to grow away from them and humanity in general.[38] Gibbons had created the blue character Rogue Trooper and explained he reused the blue skin motif for Doctor Manhattan as it visualized electrical or atomic energy while still resembling human skin tonally and "reading as Jon Osterman's skin would've read, but in a different hue." Moore incorporated the color into the story, and Gibbons noted the rest of the comic's color scheme made Manhattan unique.[56] Moore recalled that he was unsure if DC would allow the creators to depict the character as fully nude, which partially influenced how they portrayed the character.[30] Gibbons wanted to be tasteful in depicting Manhattan's nudity, selecting carefully when full frontal shots would occur and giving him "understated" genitals—like a classical sculpture—so the reader would not initially notice it.[52]

- Laurie Juspeczyk / Silk Spectre II

- The daughter of Sally Jupiter (the first Silk Spectre, with whom she has a strained relationship) and The Comedian. Of Polish heritage, she had been the lover of Doctor Manhattan for years. While Silk Spectre was originally supposed to be the Charlton superheroine Nightshade, Moore was not particularly interested in that character. Once the idea of using Charlton characters was abandoned, Moore drew more from heroines such as Black Canary and Phantom Lady.[28] A University of Dayton student paper described Laurie as impulsive—"rarely using logic to think through situations"—but also as constantly standing by her belief that each human life matters, which contrasts with most other characters in Watchmen.[57]

- Walter Joseph Kovacs / Rorschach

- A vigilante who wears a white mask that contains a symmetrical but constantly shifting ink blot pattern, he continues to fight crime in spite of his outlaw status. Moore said he was trying to "come up with this quintessential Steve Ditko character—someone who's got a funny name, whose surname begins with a 'K,' who's got an oddly designed mask". Moore based Rorschach on Ditko's creation Mr. A;[42] Ditko's Charlton character The Question also served as a template for creating Rorschach.[28] Comics historian Bradford W. Wright described the character's world view "a set of black-and-white values that take many shapes but never mix into shades of gray, similar to the ink blot tests of his namesake". Rorschach sees existence as random and, according to Wright, this viewpoint leaves the character "free to 'scrawl [his] own design' on a 'morally blank world'".[58] Moore said he did not foresee the death of Rorschach until the fourth issue when he realized that his refusal to compromise would result in him not surviving the story.[38]

Art and composition[edit]

One Reply to “Watchmen”

Comments are closed.

Watchmen theme. The upcoming movie, which is set to 2009, is from Zack Snyder (300) and is considered, by the extras, an exact copy of the graphic novel.