Ferrari theme by TOUGY

Download: Ferrari_4.p3t

(8 backgrounds)

| |

Headquarters in Maranello, Italy | |

| Company type | Public (S.p.A.) |

|---|---|

| ISIN | NL0011585146 |

| Industry | Automotive |

| Founded | 13 September 1939 in Modena, Italy (as Auto Avio Costruzioni)[1] |

| Founder | Enzo Ferrari |

| Headquarters |

44°31′57″N 10°51′51″E / 44.532447°N 10.864137°E |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people |

|

| Products | Sports cars, luxury cars |

Production output | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Owners | |

Number of employees | |

| Divisions | Scuderia Ferrari |

| Website | www |

| Footnotes / references [3] [4][5] | |

Ferrari S.p.A. (/fəˈrɑːri/; Italian: [ferˈraːri]) is an Italian luxury sports car manufacturer based in Maranello. Founded in 1939 by Enzo Ferrari (1898–1988), the company built its first car in 1940, adopted its current name in 1945, and began to produce its current line of road cars in 1947. Ferrari became a public company in 1960, and from 1963 to 2014 it was a subsidiary of Fiat S.p.A. It was spun off from Fiat's successor entity, Fiat Chrysler Automobiles, in 2016. In 2024, the Wall Street Journal described the company as having been "synonymous with opulence, meticulous craftsmanship and ridiculously fast cars for nearly a century".[6]

The company currently offers a large model range which includes several supercars, grand tourers, and one SUV. Many early Ferraris, dating to the 1950s and 1960s, count among the most expensive cars ever sold at auction. Owing to a combination of its cars, enthusiast culture, and successful licensing deals, in 2019 Ferrari was labelled the world's strongest brand by the financial consultancy Brand Finance.[7] As of May 2023, Ferrari is also one of the largest car manufacturers by market capitalisation, with a value of approximately US$52 billion.[8]

Throughout its history, the company has been noted for its continued participation in racing, especially in Formula One, where its team, Scuderia Ferrari, is the series' single oldest and most successful. Scuderia Ferrari has raced since 1929, first in Grand Prix events and later in Formula One, where since 1952 it has fielded fifteen champion drivers, won sixteen Constructors' Championships, and accumulated more race victories, 1–2 finishes, podiums, pole positions, fastest laps and points than any other team in F1 history.[9][10] Historically, Ferrari was also highly active in sports car racing, where its cars took many wins in races such as the Mille Miglia, Targa Florio and 24 Hours of Le Mans, as well as several overall victories in the World Sportscar Championship. Scuderia Ferrari fans, commonly called tifosi, are known for their passion and loyalty to the team.

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

Enzo Ferrari, formerly a salesman and racing driver for Alfa Romeo, founded Scuderia Ferrari, a racing team, in 1929. Originally intended to service gentleman drivers and other amateur racers, Alfa Romeo's withdrawal from racing in 1933, combined with Enzo's connections within the company, turned Scuderia Ferrari into its unofficial representative on the track.[11] Alfa Romeo supplied racing cars to Ferrari, who eventually amassed some of the best drivers of the 1930s and won many races before the team's liquidation in 1937.[11][12]: 43

Late in 1937, Scuderia Ferrari was liquidated and absorbed into Alfa Romeo,[11] but Enzo's disagreements with upper management caused him to leave in 1939. He used his settlement to found his own company, where he intended to produce his own cars. He called the company "Auto Avio Costruzioni", and headquartered it in the facilities of the old Scuderia Ferrari;[1] due to a noncompete agreement with Alfa Romeo, the company could not use the Ferrari name for another four years. The company produced a single car, the Auto Avio Costruzioni 815, which participated in only one race before the outbreak of World War II. During the war, Enzo's company produced aircraft engines and machine tools for the Italian military; the contracts for these goods were lucrative, and provided the new company with a great deal of capital. In 1943, under threat of Allied bombing raids, the company's factory was moved to Maranello. Though the new facility was nonetheless bombed twice, Ferrari remains in Maranello to this day.[1][12]: 45–47 [13]

Under Enzo Ferrari[edit]

In 1945, Ferrari adopted its current name. Work started promptly on a new V12 engine that would power the 125 S, which was the marque's first car, and many subsequent Ferraris. The company saw success in motorsport almost as soon as it began racing: the 125 S won many races in 1947,[16][17] and several early victories, including the 1949 24 Hours of Le Mans and 1951 Carrera Panamericana, helped build Ferrari's reputation as a high-quality automaker.[18][19] Ferrari won several more races in the coming years,[9][20] and early in the 1950s its road cars were already a favourite of the international elite.[21] Ferrari produced many families of interrelated cars, including the America, Monza, and 250 series, and the company's first series-produced car was the 250 GT Coupé, beginning in 1958.[22]

In 1960, Ferrari was reorganized as a public company. It soon began searching for a business partner to handle its manufacturing operations: it first approached Ford in 1963, though negotiations fell through; later talks with Fiat, who bought 50% of Ferrari's shares in 1969, were more successful.[23][24] In the second half of the decade, Ferrari also produced two cars that upended its more traditional models: the 1967 Dino 206 GT, which was its first mass-produced mid-engined road car,[a] and the 1968 365 GTB/4, which possessed streamlined styling that modernised Ferrari's design language.[27][28] The Dino in particular was a decisive movement away from the company's conservative engineering approach, where every road-going Ferrari featured a V12 engine placed in the front of the car, and it presaged Ferrari's full embrace of mid-engine architecture, as well as V6 and V8 engines, in the 1970s and 1980s.[27]

Contemporary[edit]

Enzo Ferrari died in 1988, an event that saw Fiat expand its stake to 90%.[29] The last car that he personally approved—the F40—expanded on the flagship supercar approach first tried by the 288 GTO four years earlier.[30] Enzo was replaced in 1991 by Luca Cordero di Montezemolo, under whose 23-year-long chairmanship the company greatly expanded. Between 1991 and 2014, he increased the profitability of Ferrari's road cars nearly tenfold, both by increasing the range of cars offered and through limiting the total number produced. Montezemolo's chairmanship also saw an expansion in licensing deals, a drastic improvement in Ferrari's Formula One performance (not least through the hiring of Michael Schumacher and Jean Todt), and the production of three more flagship cars: the F50, the Enzo, and the LaFerrari. In addition to his leadership of Ferrari, Montezemolo was also the chairman of Fiat proper between 2004 and 2010.[31]

After Montezemolo resigned, he was replaced in quick succession by many new chairmen and CEOs. He was succeeded first by Sergio Marchionne,[31] who would oversee Ferrari's initial public offering and subsequent spin-off from Fiat Chrysler Automobiles,[32][33] and then by Louis Camilleri as CEO and John Elkann as chairman.[34] Beginning in 2021, Camilleri was replaced as CEO by Benedetto Vigna, who has announced plans to develop Ferrari's first fully electric model.[35] During this period, Ferrari has expanded its production, owing to a global increase in wealth, while becoming more selective with its licensing deals.[36][37]

Motorsport[edit]

Since the company's beginnings, Ferrari has been involved in motorsport. Through its works team, Scuderia Ferrari, it has competed in a range of categories including Formula One and sports car racing, though the company has also worked in partnership with other teams.

Grand Prix and Formula One racing[edit]

The earliest Ferrari entity, Scuderia Ferrari, was created in 1929—ten years before the founding of Ferrari proper—as a Grand Prix racing team. It was affiliated with automaker Alfa Romeo, for whom Enzo had worked in the 1920s. Alfa Romeo supplied racing cars to Ferrari, which the team then tuned and adjusted to their desired specifications. Scuderia Ferrari was highly successful in the 1930s: between 1929 and 1937 the team fielded such top drivers as Antonio Ascari, Giuseppe Campari, and Tazio Nuvolari, and won 144 out of its 225 races.[12][11]

Ferrari returned to Grand Prix racing in 1947, which was at that point metamorphosing into modern-day Formula One. The team's first homebuilt Grand Prix car, the 125 F1, was first raced at the 1948 Italian Grand Prix, where its encouraging performance convinced Enzo to continue the company's costly Grand Prix racing programme.[38]: 9 Ferrari's first victory in an F1 series was at the 1951 British Grand Prix, heralding its strong performance during the 1950s and early 1960s: between 1952 and 1964, the team took home six World Drivers' Championships and one Constructors' Championship. Notable Ferrari drivers from this era include Alberto Ascari, Juan Manuel Fangio, Phil Hill, and John Surtees.[9]

Ferrari's initial fortunes ran dry after 1964, and its began to receive its titles in isolated sprees.[10] Ferrari first started to slip in the late 1960s, when it was outclassed by teams using the inexpensive, well-engineered Cosworth DFV engine.[39][40] The team's performance improved markedly in the mid-1970s thanks to Niki Lauda, whose skill behind the wheel granted Ferrari a drivers' title in 1975 and 1977; similar success was accomplished in following years by the likes of Jody Scheckter and Gilles Villeneuve.[10][41] The team also won the Constructors' Championship in 1982 and 1983.[9][42]

Following another drought in the 1980s and 1990s, Ferrari saw a long winning streak in the 2000s, largely through the work of Michael Schumacher. After signing onto the team in 1996, Schumacher gave Ferrari five consecutive drivers' titles between 2000 and 2004; this was accompanied by six consecutive constructors' titles, beginning in 1999. Ferrari was especially dominant in the 2004 season, where it lost only three races.[9] After Schumacher's departure, Ferrari won one more drivers' title—given in 2007 to Kimi Räikkönen—and two constructors' titles in 2007 and 2008. These are the team's most recent titles to date; as of late, Ferrari has struggled to outdo recently ascendant teams such as Red Bull and Mercedes-Benz.[9][10]

Ferrari Driver Academy[edit]

Ferrari's junior driver programme is the Ferrari Driver Academy. Begun in 2009, the initiative follows the team's successful grooming of Felipe Massa between 2003 and 2006. Drivers who are accepted into the Academy learn the rules and history of formula racing as they compete, with Ferrari's support, in feeder classes such as Formula Three and Formula 4.[43][44][45] As of 2019, 5 out of 18 programme inductees had graduated and become F1 drivers: one of these drivers, Charles Leclerc, came to race for Scuderia Ferrari, while the other four signed to other teams. Non-graduate drivers have participated in racing development, filled consultant roles, or left the Academy to continue racing in lower-tier formulae.[45]

Sports car racing[edit]

Aside from an abortive effort in 1940, Ferrari began racing sports cars in 1947, when the 125 S won six out of the ten races it participated in. [16] Ferrari continued to see similar luck in the years to follow: by 1957, just ten years after beginning to compete, Ferrari had won three World Sportscar Championships, seven victories in the Mille Miglia, and two victories at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, among many other races[20] These races were ideal environments for the development and promotion of Ferrari's earlier road cars, which were broadly similar to their racing counterparts.[46]

This luck continued into the first half of the 1960s, when Ferrari won the WSC's 2000GT class three consecutive times and finished first at Le Mans for six consecutive years.[47][48] Its winning streak at Le Mans was broken by Ford in 1966,[48] and though Ferrari would win two more WSC titles—one in 1967 and another in 1972[49][50]—poor revenue allocation, combined with languishing performance in Formula One, led the company to cease competing in sports car events in 1973.[24]: 621 From that point onward, Ferrari would help prepare sports racing cars for privateer teams, but would not race them itself.[51]

In 2023, Ferrari reentered sports car racing. For the 2023 FIA World Endurance Championship, Ferrari, in partnership with AF Corse, fielded two 499P sports prototypes. To commemorate the company's return to the discipline, one of the cars was numbered "50", referencing the fifty years that had elapsed since a works Ferrari competed in an endurance race.[52][53] The 499P finished first at the 2023 24 Hours of Le Mans, ending Toyota Gazoo Racing's six-year winning streak there and becoming the first Ferrari in 58 years to win the race.[54]At the 2024 24 Hours of Le Mans, Ferrari achieved its eleventh victory, second consecutive at Le Mans since 1965 with the No. 50 499P driven by Antonio Fuoco, Miguel Molina and Nicklas Nielsen. While the Ferrari No. 51 499P driven by Alessandro Pier Guidi, James Calado, a

3D Art

3D Art theme by DarkDub

Download: 3DArt.p3t

(12 backgrounds)

P3T Unpacker v0.12

Copyright (c) 2007. Anoop Menon

This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit!

Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip

Instructions:

Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme.

The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract.

The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename].

For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following:

p3textractor filename.p3t [destination path]Replace filename with the name of the p3t file, and replace [destination path] with the name of the folder you want the files to be extracted to. A destination path is not required. By default it will extract to extracted.filename.

Power Stone

Power Stone theme by Joseph Collum (PSN: rockmanjoey)

Download: PowerStone.p3t

(2 backgrounds)

Power Stone may refer to:

- Power Stone (video game), a 1999 Capcom fighting game

- Power Stone (TV series), an anime television series based on the video game

- Power Stone (Marvel Cinematic Universe), a fictional item in the Marvel Cinematic Universe

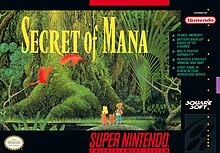

Secret of Mana

Secret of Mana theme by Tidal

Download: SecretofMana.p3t

(1 background)

| Secret of Mana | |

|---|---|

North American SNES box art | |

| Developer(s) | Square |

| Publisher(s) | Square Square Enix (mobile) |

| Director(s) | Koichi Ishii |

| Producer(s) | Hiromichi Tanaka |

| Designer(s) |

|

| Programmer(s) | Nasir Gebelli |

| Artist(s) | Shinichi Kameoka Hiroo Isono |

| Writer(s) | Hiromichi Tanaka |

| Composer(s) | Hiroki Kikuta |

| Series | Mana |

| Platform(s) | Super Nintendo Entertainment System, Mobile phone, iOS, Android |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Action role-playing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

Secret of Mana, originally released in Japan as Seiken Densetsu 2,[a] is a 1993 action role-playing game developed and published by Square for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System. It is the sequel to the 1991 game Seiken Densetsu, released in North America as Final Fantasy Adventure and in Europe as Mystic Quest, and it was the first Seiken Densetsu title to be marketed as part of the Mana series rather than the Final Fantasy series. Set in a high fantasy universe, the game follows three heroes as they attempt to prevent an empire from conquering the world with the power of an ancient flying fortress.

Rather than using a turn-based battle system like contemporaneous role-playing games, Secret of Mana features real-time battles with a power bar mechanic. The game has a unique Ring Command menu system, which pauses the action and allows the player to make decisions in the middle of battle. An innovative cooperative multiplayer system allows a second or third player to drop in and out of the game at any time. Secret of Mana was directed and designed by Koichi Ishii, programmed primarily by Nasir Gebelli, and produced by veteran Square designer Hiromichi Tanaka.

The game received acclaim for its brightly colored graphics, expansive plot, Ring Command menu system, and innovative real-time battle system. Critics also praised Hiroki Kikuta's soundtrack and the customizable artificial intelligence (AI) settings for computer-controlled allies. Retrospectively, it has been considered one of the greatest games of all time by critics.

The original version was released for the Wii's Virtual Console in Japan by Square's successor Square Enix in September 2008, and for the Wii U's Virtual Console in June 2013. The game was ported to mobile phones in Japan in 2009, and an enhanced port of the game was released for iOS in 2010 and Android in 2014. It was included in the Collection of Mana release for the Nintendo Switch in Japan in June 2017 and North America in June 2019. Nintendo also re-released Secret of Mana in September 2017 as part of the company's Super NES Classic Edition. A full 3D remake was released for the PlayStation 4, PlayStation Vita and Windows in February 2018.

Gameplay[edit]

Like many other role-playing games of the 16-bit era, Secret of Mana displays a top-down perspective, in which the player characters navigate the terrain and fight off hostile creatures. The game features three such characters: the hero, the girl, and the sprite, named Randi, Primm, and Popoi outside the initial North American and European releases. The player can choose to control each of the characters at any time; whichever character is currently selected, the other two companions are controlled via artificial intelligence. The game may be played simultaneously by up to three players,[2][3] made possible by the Super Multitap accessory for the Super NES console.[4] The Virtual Console version of the game supports three-player gameplay via additional GameCube controllers or Classic Controllers.[5]

Each character possesses individual strengths and weaknesses. The hero, while unable to use magic, masters weapons at a quicker rate; the girl is a healer, able to cast restorative and support spells; and the sprite casts offensive magic to damage and impair enemies.[5] Upon collecting enough experience points in battle, each character increases in level and improves in areas such as strength and evasion. The trio can rest in towns, where they can regain hit points or purchase restorative items and equipment. Options such as changing equipment, casting spells, or checking status are performed by cycling through the game's Ring Commands, a circular menu which hovers over the currently controlled party member.[3][4][5] The game is momentarily paused whenever the Ring Commands appear.[6]

Combat takes place in real-time.[3] Located at the bottom of the screen is a power bar,[7][8] a gauge that determines the amount of damage done to an enemy when attacking. Swinging a weapon causes the gauge to empty and then quickly recharge, allowing that character to attack at full strength. The party wields eight different types of weaponry: sword, spear, bow, axe, boomerang, glove, whip, and javelin. All weapons can be upgraded eight times, and repeated use of a weapon increases its skill level to a maximum of eight, unlocking a new special attack with each level. Weapons are upgraded with Weapon Orbs, which are found in dungeons or earned by defeating certain bosses.[3] The player takes each Orb to a blacksmith, located in most towns, who uses it to reforge one weapon.[2][9]

In order to learn magic, the party must rescue spirits known as Elementals. The eight Elementals represent different elements—such as water, earth, and life—and each provides the player with specific spells. Magic has skill levels similar to weapons, but each magic spell costs magic points to cast.[2]

At the start of the game, to reach a destination, players must traverse an enemy-infested countryside. Travel may be expedited with Cannon Travel Centers, where the party may be launched to faraway destinations via a giant cannon. Cannon Travel usually requires a fee, but is mandatory to visit other continents later on.[4] Later, the party is given access to Flammie, a miniature dragon which is controlled by the player and able to fly freely across the world, represented by an overworld map.[10] These sequences make use of the SNES's Mode 7 capability to create a rotatable background, giving the illusion that the ground beneath Flammie is rendered in three dimensions. While riding Flammie, the player may access either the "rotated map", which presents the world as a globe, or the "world map", a two-dimensional view of the overworld.[11]

Plot[edit]

Setting and characters[edit]

The story takes place in a high fantasy world, which contains an ethereal energy source named "mana". An ancient, technologically advanced civilization exploited mana to construct the "Mana Fortress", a flying warship. This angered the world's gods, who sent giant beasts to war with the civilization. The conflict was globally destructive and nearly exhausted all signs of mana in the world, until a hero used the power of the Mana Sword to destroy the fortress and the civilization. The world began to recover in peace. As the game opens, an empire seeks eight Mana Seeds, which when "unsealed" will restore mana to the world and allow the empire to restore the Mana Fortress.[12]

The three main characters do not have names in the original SNES release, though their names appear in the manual of the Japanese release; their names were added into the game in the iOS port worldwide. In all versions, the player can choose to name the characters whatever they wish. The hero (ランディ, Randi),[13] a young boy, is adopted by the Elder of Potos before the start of the game, after the boy's mother disappears. The girl (プリム, Primm)[13] is in love with a warrior named Dyluck, who was ordered by the king to attack Elinee's Castle. Angered by the king's actions and by her father's attempt to arrange her marriage to a local nobleman, she leaves the castle to save Dyluck and to accompany the hero as well.[14] The hero meets a sprite child (ポポイ, Popoi)[13] at the Dwarf Village. The sprite lives with a dwarf and goes with the characters to learn more about their family. It does not remember anything about its past, so it joins the team to try to recover its memories.[15]

Story[edit]

The game begins as three boys from the small Potos village disobey their Elder's instructions and trespass into a local waterfall, where a treasure is said to be kept. One of the boys stumbles and falls into the lake, where he finds a rusty sword embedded in a stone. Guided by a disembodied voice, he pulls the sword free, inadvertently unleashing monsters in the surrounding countryside of the village. The villagers interpret the sword's removal as a bad omen and banish the boy from Potos forever.[16] A traveling knight named Jema recognizes the blade as the legendary Mana Sword and encourages the hero to re-energize it by visiting the eight Mana Temples.[17]

During his journey, the hero is joined by the girl and the sprite. Throughout their travels, the trio is pursued by the Empire. The Emperor and his subordinates are being manipulated by Thanatos, an ancient sorcerer who hopes to create a "new, peaceful world".[18] Due to his own body's deterioration, Thanatos is in need of a suitable body to possess. After placing the entire kingdom of Pandora under a trance, he abducts two candidates: Dyluck, now enslaved, and a young Pandoran girl named Phanna; he eventually chooses to possess Dyluck.[19]

The Empire succeeds in unsealing all eight Mana Seeds. However, Thanatos betrays the Emperor and his henchmen, killing them and seizing control of the Mana Fortress for himself. The hero and his party journey to locate the Mana Tree, the focal point of the world's life energy. Anticipating their arrival, Thanatos positions the Mana Fortress over the Tree and destroys it. The charred remains of the Tree speak to the heroes, explaining that a giant dragon called the Mana Beast will soon be summoned to combat the Fortress. The Beast has little control over its rage and will likely destroy the world as well.[20] The Mana Tree also reveals that it was once the human wife of Serin, the original Mana Knight and the hero's father. The voice heard at Potos' waterfall was that of Serin's ghost.[21]

The trio flies to the Mana Fortress and confronts Thanatos, who is preparing to transfer his mind into Dyluck. With the last of his strength, Dyluck warns that Thanatos has sold his soul to the underworld and must not be allowed to have the Fortress.[22] Dyluck kills himself, forcing Thanatos to revert to a skeletal lich form, which the party defeats. The Mana Beast finally flies in and attacks the Fortress. The hero expresses reluctance to kill the Beast, fearing that with the dispersal of Mana from the world, the sprite will vanish.[23] With the sprite's encouragement, he uses the fully energized Mana Sword to slay the Beast, causing it to explode and transform into snow.[24] At the conclusion of the game, the sprite child vanishes into an astral plane, the girl is returned home and the hero is seen welcomed back in Potos, returning the Mana Sword to its place beneath the waterfall.

Development[edit]

Secret of Mana was directed and designed by Koichi Ishii, the creator of the game's Game Boy predecessor, Final Fantasy Adventure. He has stated that he feels Secret of Mana is more "his game" than other projects he has worked on, such as the Final Fantasy series.[25] The game was programmed primarily by Nasir Gebelli and produced by veteran Square designer Hiromichi Tanaka. The team hoped to build on the foundation of Final Fantasy Adventure, and they included several modified elements from that game and from other popular Square titles in Secret of Mana. In addition to having better graphics and sound quality than its predecessor, the attack power gauge was changed to be more engaging, and the weapon leveling system replaced Final Fantasy Adventure's system of leveling up the speed of the attack gauge.[8] The party system also received an upgrade from the first Mana game: instead of temporary companions who could not be upgraded, party members became permanent protagonists and could be controlled by other players.[8] The multiplayer component was not a part of the original design, but was added when the developers realized that they could easily make all three characters human-controlled.[25]

The real-time battle system used in Secret of Mana has been described by its creators as an extension of the battle system used in the first three flagship Final Fantasy titles. The system for experience points and leveling up was taken from Final Fantasy III.[26] According to Tanaka, the game's battle system features mechanics that had first been considered for Final Fantasy IV. Similarly, unused features in Secret of Mana were appropriated by the Chrono Trigger team, which (like Final Fantasy IV) was in production at the time.[25] According to Tanaka, the project was originally intended to be Final Fantasy IV, with a "more action-based, dynamic overworld". However, it "wound up not being" Final Fantasy IV anymore, but instead became a separate project codenamed "Chrono Trigger" during development, before finally becoming Seiken Densetsu 2. Tanaka said that it "always felt like a sequel" to Final Fantasy III for him.[27]

Secret of Mana was originally planned to be a launch title for the SNES-CD add-on.[28][29] After the contract between Nintendo and Sony to produce the add-on failed, and Sony repurposed its work on the SNES-CD into the competing PlayStation console, Square adapted the game for the SNES cartridge format. The game had to be altered to fit the storage space of a SNES game cartridge, which is much smaller than that of a CD-ROM.[30] The developers initially resisted continuing the project without the CD add-on, believing that too much of the game would have to be cut, but they were overruled by company management. As a result of the hardware change, several features had to be cut from the game, and some completed work needed to be redone.[25][29] One of the most significant changes was the removal of the option to take multiple routes through the game that led to several possible endings, in contrast to the linear journey in the final product.[8] The plot that remained was different from the original conception, and Tanaka has said that the original story had a much darker tone.[25] Ishii has estimated that up to forty percent of the planned game was dropped to meet the space limitations, and critics have suggested that the hardware change led to technical problems when too much happens at once in the game.[25][31] Secret of Mana was announced as being released in July 1993 as recently as that April, marketed as a "Party Action RPG", before eventually being released in August instead for the Japanese market.[32] In South Korea, it was released the same month in August 1993.[33]

The English translation for Secret of Mana was completed in only 30 days, mere weeks after the Japanese release,[28] and the North American localization was initially advertised as Final Fantasy Adventure 2.[34] Critics have suggested that the translation was done hastily so that the game could be released in North America for the 1993 holiday season.[30] According to translator Ted Woolsey, a large portion of the game's script was cut out in the English localization due to space limitations.[28][35] To display text on the main gameplay screen, the English translation uses a fixed-width font, which limits the amount of space available to display text. Woolsey was unhappy that he had to trim conversations to their bare essentials and that he had so little time for translation, commenting that it "nearly killed me".[36] The script was difficult to translate as it was presented to Woolsey in disordered groups of text, like "shuffling a novel".[35] Other localizations were done in German and French. The Japanese release only named the three protagonists in the manual,[37] while Western versions omitted the characters' names until the enhanced port on the iOS.[38][39]

Music[edit]

The original score for Secret of Mana was composed and produced by Hiroki Kikuta. Kenji Ito, who had composed the soundtrack for Final Fantasy Adventure, was originally slated for the project, but was replaced with Kikuta after he had started on other projects, such as Romancing SaGa. Secret of Mana was Kikuta's first video game score, and he encountered difficulties in dealing with the hardware limitations of the Super NES. Kikuta tried to express in the music two "contrasting styles" to create an original score which would be neither pop music nor standard game music.[40] Kikuta worked on the music mostly by himself, spending nearly 24 hours a day in his office, alternating between composing and editing to create a soundtrack that would be, according to him, "immersive" and "three-dimensional".[41] Rather than having sound engineers create the samples of instruments like most game music composers of the time, Kikuta made his own samples that matched the hardware capabilities of the Super NES. These custom samples allowed him to know exactly how each piece would sound on the system's hardware, so he did not have to worry about differences between the original composition and the Super NES.[42] Kikuta stated in 2001 that he considered the score for Secret of Mana his favorite creation.[43]

The soundtrack's music includes both "ominous" and "light-hearted" tracks, and is noted for its use of bells and "dark, solemn pianos".[44] Kikuta's compositions for the game were partly inspired by natural landscapes, as well as music from Bali.[45][46] Hardware limitations made the title screen to the game slowly fade in, and Kikuta designed the title track to the game, "Fear of the Heavens", to sync up with the screen. At that time, composers rarely tried to match a game's music to its visuals. Kikuta also started the track off with a "whale noise", rather than a traditional "ping", in order to try to "more deeply connect" the player with the game from the moment it started up. Getting the sound to work with the memory limitations of the Super NES was a difficult technical challenge.[42]

An official soundtrack album, Seiken Densetsu 2 Original Sound Version, was released in Japan in August 1993, containing 44 musical tracks from the game. An English version, identical to the Japanese original aside from its localized packaging and track titles, was later released in North America in December 1994 as Secret of Mana Original Soundtrack, making Secret of Mana one of the first Japanese games to inspire a localized soundtrack release outside of Japan.[44] An album of arranged music from Secret of Mana and its sequel Seiken Densetsu 3 was produced in 1993 as Secret of Mana+. The music in the album was all composed and arranged by Kikuta. Secret of Mana+ contains a single track, titled "Secret of Mana", that incorporates themes from the music of both Secret of Mana and Seiken Densetsu 3, which was still under development at the time.[47] The style of the album has been described by critics as "experimental", using "strange sounds" such as waterfalls, bird calls, cell phone sounds, and "typing" sounds.[48] The music has also been described by critics as covering many different musical styles, such as "Debussian impressionist styles, his own heavy electronic and synth ideas, and even ideas of popular musicians".[47] The latest album of music from the game is a 2012 arranged album titled Secret of Mana Genesis / Seiken Densetsu 2 Arrange Album. The 16 tracks are upgraded versions of the original Super NES tracks, and Kikuta said in the liner notes for the album that they are "how he wanted the music to sound when he wrote it", without the limitations of the Super NES hardware. Critics such as Patrick Gann of RPGFan, however, noted that the differences were minor.[49] Music for the 2018 remake, which features remastered versions of the original soundtrack, was overseen by Kikuta and arranged by numerous game composers, such as Yuzo Koshiro and Tsuyoshi Sekito.[50] The soundtrack was released as an album, also titled Secret of Mana Original Soundtrack, shortly after the remake's release in February 2018.[51] A rendition of the soundtrack was commissioned for the first ever BBC Proms gaming music concert in 2022.[52]

Re-releases[edit]

In 1999, Square announced they would be porting Secret of Mana to Bandai's handheld system WonderSwan Color as one of nine planned games for the system.[53] No such port was ever released. A mobile phone port of Secret of Mana was released on October 26, 2009.[54] A port of the game for iOS was revealed at E3 2010, and released on Apple's App Store on December 21, 2010.[55] The port fixed several bugs, and the English script was both edited and retranslated from the original Japanese.[56] The enhanced port from the iOS version was released on Android devices in 2014.[57] A port for the Nintendo Switch was released with ports of Final Fantasy Adventure and Trials of Mana as part of the Collection of Mana on June 1, 2017, in Japan, and June 11, 2019 in North America.[58][59] The game was released as one of the games included on the Super NES Classic Edition on September 29, 2017.[60]

In August 2017, a 3D remake of the game was announced for PlayStation 4, PlayStation Vita and Windows and was released on February 15, 2018.[61] The remake was developed by Q Studios for Square Enix.[62]

Reception and legacy[edit]

| Publication | Score |

|---|---|

| Dragon | |

| Edge | 9/10[64] |

| Electronic Gaming Monthly | 35/40[65] |

| Famitsu | 33/40[66] |

| Game Informer | 9.25/10[67] |

| GameFan | 363/400[68] |

| GamePro | 18/20[69] |

| Nintendo Power | 3.9/5[70] |

| Official Nintendo Magazine | 93%[71] |

Sales[edit]

The initial shipment of games in Japan sold out within days of the release date.[72] Dengeki Oh magazine ranked it the second best-selling video game of 1993 in Japan, where 1.003 million units were sold that year, just below

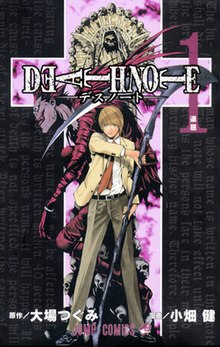

Death Note theme by Markese L. Jackson Download: DeathNote_3.p3t

Death Note (stylized in all caps) is a Japanese manga series written by Tsugumi Ohba and illustrated by Takeshi Obata. It was serialized in Shueisha's shōnen manga magazine Weekly Shōnen Jump from December 2003 to May 2006, with its chapters collected in 12 tankōbon volumes. The story follows Light Yagami, a genius high school student who discovers a mysterious notebook: the "Death Note", which belonged to the shinigami Ryuk, and grants the user the supernatural ability to kill anyone whose name is written in its pages. The series centers around Light's subsequent attempts to use the Death Note to carry out a worldwide massacre of individuals whom he deems immoral and to create a crime-free society, using the alias of a god-like vigilante named "Kira", and the subsequent efforts of an elite Japanese police task force, led by enigmatic detective L, to apprehend him.

A 37-episode anime television series adaptation, produced by Madhouse and directed by Tetsurō Araki, was broadcast on Nippon Television from October 2006 to June 2007. A light novel based on the series, written by Nisio Isin, was also released in 2006. Additionally, various video games have been published by Konami for the Nintendo DS. The series was adapted into three live-action films released in Japan in June, November 2006, and February 2008, and a television drama in 2015. A miniseries titled Death Note: New Generation and a fourth film were released in 2016. An American film adaptation was released exclusively on Netflix in August 2017, and a series is reportedly in the works.

Death Note media, except for video games and soundtracks, is licensed and released in North America by Viz Media. The episodes from the anime first appeared in North America as downloadable from IGN before Viz Media licensed it. The series was aired on YTV's Bionix programming block in Canada and on Adult Swim in the United States with a DVD release following. The live-action films briefly played in certain North American theaters, in 2008, before receiving home video releases. By April 2015, the Death Note manga had over 30 million copies in circulation, making it one of the best-selling manga series.

In Tokyo, a disaffected high school student named Light Yagami finds the "Death Note", a mysterious black notebook with rules that can end anyone's life in seconds as long as the writer knows both the target's true name and face. Light uses the notebook to kill high-profile criminals and is visited by Ryuk, a "shinigami" and the Death Note's previous owner. Ryuk, invisible to anyone who has not touched the notebook, reveals that he dropped the notebook into the human world out of boredom and is amused by Light's actions.[5]

Global media suggest that a single mastermind is responsible for the mysterious murders and name them "Kira" (キラ, the Japanese transliteration of the word "killer"). Interpol requests the assistance of the enigmatic detective L to assist in their investigation. L tricks Light into revealing that he is in the Kanto region of Japan by manipulating him to kill a decoy. Light vows to kill L, whom he views as obstructing his plans. L deduces that Kira has inside knowledge of the Japanese police investigation, led by Light's father, Soichiro Yagami. L assigns a team of FBI agents to monitor the families of those connected with the investigation and designates Light as the prime suspect. Light graduates from high school to college. L recruits Light into the Kira Task Force.

Actress-model Misa Amane obtains a second Death Note from a shinigami named Rem and makes a deal for shinigami eyes, which reveal the names of anyone whose face she sees, at the cost of half her remaining lifespan. Seeking to have Light become her boyfriend, Misa uncovers Light's identity as the original Kira. Light uses her love for him to his advantage, intending to use Misa's shinigami eyes to discern L's true name. L deduces that Misa is likely the second Kira and detains her. Rem threatens to kill Light if he does not find a way to save Misa. Light arranges a scheme in which he and Misa temporarily lose their memories of the Death Note, and has Rem pass the Death Note to Kyosuke Higuchi of the Yotsuba Group.

With memories of the Death Note erased, Light joins the investigation and, together with L, deduces Higuchi's identity and arrests him. Light regains his memories and uses the Death Note to kill Higuchi, regaining possession of the book. After restoring Misa's memories, Light instructs her to begin killing as Kira, causing L to cast suspicion on Misa. Rem realizes Light's plan to have Misa sacrifice herself to kill L. After Rem kills L, she disintegrates and Light obtains her Death Note. The task force agrees to have Light operate as the new L. The investigation stalls but crime rates continue to drop.

Four years later, cults worshipping Kira have risen. L's potential successors are introduced: Near and Mello. Mello joins the mafia whilst Near joins forces with the US government. Mello kidnaps Director Takimura, who is killed by Light. Mello kidnaps Light's sister and exchanges her for the Death Note, using it to kill almost all of Near's team. A Shinigami named Sidoh goes to Earth to reclaim his notebook and ends up meeting and helping Mello. Light uses the notebook to find Mello's hideout, but Soichiro is killed in the mission. Mello and Near exchange information and Mello kidnaps Mogi and gives him to Near. Kira's supporters attack Near's group, but they escape. Shuichi Aizawa, one of the task force members, becomes suspicious of Light and meets with Near. As suspicion falls again on Misa, Light passes Misa's Death Note to Teru Mikami, a fervent Kira supporter, and appoints newscaster Kiyomi Takada as Kira's public spokesperson. Near has Mikami followed whilst Aizawa's suspicions are confirmed. Realizing that Takada is connected to Kira, Mello kidnaps her. Takada kills Mello but is killed by Light. Near arranges a meeting between Light and the current Kira Task Force members. Light tries to have Mikami kill Near as well as all the task force members, but Mikami's Death Note fails to work, having been replaced with a decoy. Near proves Light is Kira discovering Mikami had not written down Light's name. Light is wounded in a scuffle and begs Ryuk to write the names of everyone present. Ryuk instead writes down Light's name in his Death Note, as he had promised to do the day they met, and Light dies.

One year later, the world has returned to normal and the Kira Taskforce Members are conflicted over whether they made the right decision. Meanwhile, cults continue to worship Kira.

Three years later, Near, now functioning as the new L, receives word that a new Kira has appeared. Hearing that the new Kira is randomly killing people, Near concludes that the new Kira is an attention-seeker and denounces the new Kira as "boring" and not worth catching. A shinigami named Midora approaches Ryuk and gives him an apple from the human realm, in a bet to see if a random human could become the new Kira, but Midora loses the bet when the human writes his own name in the Death Note after hearing Near's announcement. Ryuk tells Midora that no human would ever surpass Light as the new Kira.

Another ten years later, Ryuk returns to Earth and gives the Death Note to Minoru Tanaka, the top-scoring student in Japan, hoping that he will follow in Light Yagami's footsteps. On explaining the rules to Minoru, Ryuk is surprised when he returns the notebook and tells him to return it and his memory of their encounter to him in two years' time. Two years later, on receiving the notebook back from Ryuk, Minoru reveals he has no plans to use it himself but rather he plans to auction it off to the governments of the world, with Ryuk's help sending his offer out as "a-Kira", having waited two years until he was old enough to have a bank account to allow his plan to work. Elsewhere, Near (as L) is revealed to be developing technology meant to track and eventually find a method of destroying Shinigami, although it is not yet advanced enough to be useful. After selling the Death Note to U.S. President Donald Trump for a sum that would ensure every Japanese citizen under the age of 60 would be financially set for life, Minoru relinquishes his ownership and memory of his plan to Ryuk, assuring his own anonymity, while Trump is left unable to use the Death Note after the King of Death creates a new rule disallowing the Death Note to be sold, and he secretly returns it to Ryuk. Minoru collapses to the ground in the bank after withdrawing his savings. It is revealed that Ryuk wrote his name in the Death Note next to Light's. He longs for a human who will use the notebook for a longer period of time.

The Death Note concept derived from a rather general concept involving Shinigami and "specific rules".[6] Author Tsugumi Ohba wanted to create a suspense series because the genre had some suspense series available to the public. After the publication of the pilot chapter, the series was not expected to receive approval as a serialized comic. Learning that Death Note had received approval and that Takeshi Obata would create the artwork, Ohba said, they "couldn't even believe it".[7] Due to positive reactions, Death Note became a serialized manga series.[8]

"Thumbnails" incorporating dialogue, panel layout and basic drawings were created, reviewed by an editor and sent to Takeshi Obata, the illustrator, with the script finalized and the panel layout "mostly done". Obata then determined the expressions and "camera angles" and created the final artwork. Ohba concentrated on the tempo and the amount of dialogue, making the text as concise as possible. Ohba commented that "reading too much exposition" would be tiring and would negatively affect the atmosphere and "air of suspense". The illustrator had significant artistic licence to interpret basic descriptions, such as "abandoned building",[9] as well as the design of the Death Notes themselves.

When Ohba was deciding on the plot, they visualized the panels while relaxing on their bed, drinking tea, or walking around their house. Often the original draft was too long and needed to be refined to finalize the desired "tempo" and "flow". The writer remarked on their preference for reading the previous "two or four" chapters carefully to ensure consistency in the story.[6]

The typical weekly production schedule consisted of five days of creating and thinking and one day using a pencil to insert dialogue into rough drafts; after this point, the writer faxed any initial drafts to the editor. The illustrator's weekly production schedule involved one day with the thumbnails, layout, and pencils and one day with additional penciling and inking. Obata's assistants usually worked for four days and Obata spent one day to finish the artwork. Obata said that when he took a few extra days to color the pages, this "messed with the schedule". In contrast, the writer took three or four days to create a chapter on some occasions, while on others they took a month. Obata said that his schedule remained consistent except when he had to create color pages.[10]

Ohba and Obata rarely met in person during the creation of the serialized manga; instead, the two met with the editor. The first time they met in person was at an editorial party in January 2004. Obata said that, despite the intrigue, he did not ask his editor about Ohba's plot developments as he anticipated the new thumbnails every week.[7] The two did not discuss the final chapters with one another and continued talking only with the editor. Ohba said that when they asked the editor if Obata had "said anything" about the story and plot, the editor responded: "No, nothing".[9]

Ohba claims that the series ended more or less in the manner that they intended for it to end; they considered the idea of L defeating Light Yagami with Light dying but instead chose to use the "Yellow Box Warehouse" ending. According to Ohba, the details had been set "from the beginning".[8] The writer wanted an ongoing plot line instead of an episodic series because Death Note was serialized and its focus was intended to be on a cast with a series of events triggered by the Death Note.[11] 13: How to Read states that the humorous aspects of Death Note originated from Ohba's "enjoyment of humorous stories".[12]

When Ohba was asked, during an interview, whether the series was meant to be about enjoying the plot twists and psychological warfare, Ohba responded by saying that this concept was the reason why they were "very happy" to place the story in Weekly Shōnen Jump.[10]

The core plot device of the story is the "Death Note" itself, a black notebook with instructions (known as "Rules of the Death Note") written on the inside. When used correctly, it allows anyone to commit a murder, knowing only the victim's name and face. According to the director of the live-action films, Shusuke Kaneko, "The idea of spirits living in words is an ancient Japanese concept.... In a way, it's a very Japanese story".[13]

Artist Takeshi Obata originally thought of the books as "Something you would automatically think was a Death Note". Deciding that this design would be cumbersome, he instead opted for a more accessible college notebook. Death Notes were originally conceived as changing based on time and location, resembling scrolls in ancient Japan, or the Old Testament in medieval Europe. However, this idea was never used.[14]

Writer Tsugumi Ohba had no particular themes in mind for Death Note. When pushed, he suggested: "Humans will all eventually die, so let's give it our all while we're alive".[15] In a 2012 paper, author Jolyon Baraka Thomas characterised Death Note as a psychological thriller released in the wake of the 1995 Tokyo subway sarin attack, saying that it examines the human tendency to express itself through "horrific" cults.[16]

The Death Note process began when Ohba brought thumbnails for two concept ideas to Shueisha; Ohba said that the Death Note pilot, one of the concepts, was "received well" by editors and attained positive reactions from readers.[8] Ohba described keeping the story of the pilot to one chapter as "very difficult", declaring that it took over a month to begin writing the chapter. He added that the story had to revive the killed characters with the Death Eraser and that he "didn't really care" for that plot device.[17]

Obata said that he wanted to draw the story after he heard of a "horror story featuring shinigami".[7] According to Obata, when he first received the rough draft created by Ohba, he "didn't really get it" at first, and he wanted to work on the project due to the presence of shinigami and because the work "was dark".[17] He also said he wondered about the progression of the plot as he read the thumbnails, and if Jump readers would enjoy reading the comic. Obata said that while there is little action and the main character "doesn't really drive the plot", he enjoyed the atmosphere of the story. He stated that he drew the pilot chapter so that it would appeal to himself.[17]

Ohba brought the rough draft of the pilot chapter to the editorial department. Obata came into the picture at a later point to create the artwork. They did not meet in person while creating the pilot chapter. Ohba said that the editor told him he did not need to meet with Obata to discuss the pilot; Ohba said "I think it worked out all right".[7]

Tetsurō Araki, the director, said that he wished to convey aspects that "made the series interesting" instead of simply "focusing on morals or the concept of justice". Toshiki Inoue, the series organizer, agreed with Araki and added that, in anime adaptations, there is a lot of importance in highlighting the aspects that are "interesting in the original". He concluded that Light's presence was "the most compelling" aspect; therefore the adaptation chronicles Light's "thoughts and actions as much as possible". Inoue noted that to best incorporate the manga's plot into the anime, he "tweak[ed] the chronology a bit" and incorporated flashbacks that appear after the openings of the episodes; he said this revealed the desired tensions. Araki said that, because in an anime the viewer cannot "turn back pages" in the manner that a manga reader can, the anime staff ensured that the show clarified details. Inoue added that the staff did not want to get involved with every single detail, so the staff selected elements to emphasize. Due to the complexity of the original manga, he described the process as "definitely delicate and a great challenge". Inoue admitted that he placed more instructions and notes in the script than usual. Araki added that because of the importance of otherwise trivial details, this commentary became crucial to the development of the series.[18]

Araki said that when he discovered the Death Note anime project, he "literally begged" to join the production team; when he joined he insisted that Inoue should write the scripts. Inoue added that, because he enjoyed reading the manga, he wished to use his effort.[18]

Death Note, written by Tsugumi Ohba and illustrated by Takeshi Obata, was serialized in Shueisha's shōnen manga magazine Weekly Shōnen Jump from December 1, 2003,[19][20] to May 15, 2006.[b][20] The series' 108 chapters were collected into twelve tankōbon volumes by Shueisha, released from April 2, 2004,[23] to July 4, 2006.[24] A one-shot chapter, titled "C-Kira" (Cキラ編, C-Kira-hen) ("Death Note: Special One-Shot"), was published in Weekly Shōnen Jump on February 9, 2008. Set two years after the manga's epilogue, it sees the introduction of a new Kira and the reactions of the main characters in response to the copycat's appearance.[25] Several Death Note yonkoma (four-panel comics) appeared in Akamaru Jump. The yonkoma was written to be humorous. The Akamaru Jump issues that printed the comics include 2004 Spring, 2004 Summer, 2005 Winter, and 2005 Spring. In addition Weekly Shōnen Jump Gag Special 2005 included some Death Note yonkoma in a Jump Heroes Super 4-Panel Competition.[17] Shueisha re-released the series in seven bunkoban volumes from March 18 to August 19, 2014.[26][27] On October 4, 2016, all 12 original manga volumes and the February 2008 one-shot were released in a single All-in-One Edition, consisting of 2,400 pages in a single book.[28][29]

In April 2005, Viz Media announced that they had licensed the series for English release in North America.[30] The twelve volumes were released from October 10, 2005, to July 3, 2007.[31][32] The manga was re-released in a six-volume omnibus edition, dubbed "Black Edition".[33][34] The volumes were released from December 28, 2010, to November 1, 2011.[35][36] The All-in-One Edition was released in English on September 6, 2017, resulting in the February 2008 one-shot being released in English for the first time.[37]

In addition, a guidebook for the manga was also released on October 13, 2006. It was named Death Note 13: How to Read and contained data relating to the series, including character profiles of almost every character that is named, creator interviews, behind the scenes info for the series and the pilot chapter that preceded Death Note. It also reprinted all of the yonkoma serialized in Akamaru Jump and the Weekly Shōnen Jump Gag Special 2005.

Resistance theme by Landser Download: Resistance.p3t Resistance may refer to:

Patapon 2 theme by original_copycat Download: Patapon2.p3t Patapon 2[a] is a 2008 video game co-developed by Pyramid and Japan Studio and published by Sony Computer Entertainment for the PlayStation Portable (PSP). It is a direct sequel to Patapon, and like its predecessor, uses the same unique genre that combines rhythm and strategy. The game was released in Japan in November 2008, in PAL regions in March 2009, in North America in May 2009, and ported to the PlayStation 4 Worldwide on January 30, 2020.

After the Patapon and Zigoton tribe finish the construction of their ship, they set sail to continue their journey to Earthend to gaze upon "IT". After some time at sea, their ship is struck down by a sea monster and both Patapons and Zigotons drift ashore on an unknown island where they encounter a new enemy tribe known as the Karmen and a lone Patapon known as "Hero". The player takes the role of an invisible deity known as The Mighty Patapon and commands the Patapon Tribe to march, attack, defend, and retreat. The game introduces a new way to evolve the Patapon army, and new units to unlock including a singular Hero Patapon that can be used for four-player ad hoc multiplayer mode.

A sequel titled Patapon 3 was released on April 12, 2011, in North America, April 15, 2011, in Europe, and on April 28, 2011, in Japan.

The core gameplay of Patapon 2 is almost identical to its predecessor. It is a video game that the player controls in a manner similar to rhythm games. The player is directly controlled by a tribe of Patapon warriors; to command the warriors, the player inputs specific sequences using the face buttons on the PSP, each representing a "talking drum", in time to a drum rhythm. These sequences order the tribe to move forward on the linear battlefield, attack, defend, and other actions. If the player inputs an unknown sequence or enters them off the main rhythm, the tribe will become confused and stop whatever they are doing. However, repeatedly entering a proper sequence in sync with the rhythm will lead the tribe into a "Fever" increasing their attack and defensive bonuses. The tribe will stop doing anything after performing the last entered command if the player does not enter any more commands. For example, some commands are square, square, square, circle (Pata, Pata, Pata, Pon.), which has them march forward and circle, circle, square, circle (Pon, Pon, Pata, Pon.), which makes them attack.

The game is divided into several missions. Prior to each mission, the player can recruit new troops and assemble formations, equip troops with weapons and armor gained from the spoils of war, or crafted from certain minigames. The player can return to an earlier mission to acquire additional resources and equipment to build up their troops before a larger battle.

Patapon 2 introduces four types of units: The bird-riding and Harpoon-wielding Toripons, the robot-armed Robopons, the Wand-wielding Mahopons, and the singular Heropon.[1] Patapon classes can now be unlocked through the evolutionary tree. Also, Rarepon can be made without sacrificing Patapon to make space for newer ones. To maintain an incentive for collecting items, there is an abundant amount of classes of Patapon to rely upon, some Patapon such as the "Pyokoran" Rarepon being nimble in battle as well being immune to freezing but are vulnerable to fire damage. Another change is that a Patapon can level up by using more material with effects amplifying at every 5 levels to a maximum of 10.

The Heropon is a singular hero unit that can adopt any unlocked class of their choice with a powerful special attack to deliver to unsuspecting foes. Players can change their masks for different stats, like elemental resistance or attack speed. They also can be revived but takes longer to revive with each death. In addition, if Hatapon is alone while the Heropon is reviving, the mission ends. Each "Hero" persona also has a special move that can only be activated in Fever mode and must have a perfect beat. This special ability shows a spirit above him and allows him to have a special damage effect on opponents like The Iron Fist (Yaripon), Broken Arrow (Yumipon).

Patapon designer Hiroyuki Kotani has revealed that the multiplayer mode stems from the single-player mode, the former of which will involve giant eggs. These eggs contain Masks for the Hero Patapon to wear or new CPU Kumopons. To hatch the eggs, four players must defend the egg on an enemy-laden multiplayer battleground, while moving it to a special egg-hatching altar. At this altar, all players must perform a hatching ceremony, which involves playing their rhythms in synchronization to crack the egg.

The story continues from the previous game. The ship the Patapons and Zigotons have constructed has been finally completed and they have set sail for new lands. On their way there, they are attacked by a Kraken who easily defeats them and sends the Patapons into the ocean to be washed ashore in a strange new land (which is actually and originally their homeland, the Patapolis) where they come up against another tribe called the Karmen. Now it is a battle to defeat the Karmen and find out who is their true enemy. Early in the game, the Patapons discover the mysterious "Hero", who wears a mask that boosts his abilities. He has lost his memory, and his true identity is forgotten, hidden, and unknown. Later, the Patapons fight against the Akumapons, and the "Dark One" (who is actually Makoton, the Zigoton that was killed in the first game with Baban, and now was reincarnated), who gave his soul to the demons for power. Gong the Hawkeye and his fellow Zigotons appear once more, to assist the Patapons against the Karmen.

During the course of a game, the player learns of a legend, that the world was broken and the Patapons ruined because a Wakapon broke the "World Egg". At the second to last stage, the player finds out that the Hero was actually the Wakapon who broke the egg, and that the Karmen tribe was the Patapon's ancestral enemy, knowing them as the ones who overtook the Patapon Ancients. The Patapon Princess was trapped inside an egg by Ormen Karmen, the leader of the Karmens, who plans to make the Princess his queen.

After defeating the demon Dettankarmen that the Karmens summoned, the Patapons journey to the end of a bridge, only to find and break an egg. Dazzled by the bright light that emerges from the egg, the Patapons assume they have found "IT" at Earthend, which they have been searching since the first game. However, the Patapon Princess emerges from the egg, compliments them on their job well done, and tells the Hero that he has a new task - to restore the world and find the true Earthend.

At the end of the game, the Patapons are seen working with the Karmen and Zigotons to fix the bridge that will lead them to the other side of the land.

Rob Smith writes that new "characters such as the bird-riding Toripon, the Robopon with huge fists, and the magic-using Mahopon provide fresh attack types and original personalities for your almighty ruler to manage."[2] In an interview attached to the same article, Hiroyuki Kotani adds that all "the new characters ended up... attractive from a fundamental gameplay standpoint, so I picked the ones I liked the most."[3] When asked, "From all the characters...is any one of them your personal favorite?" Kotani answered, "I love Gong, the leader of the Zigotons. In fact, I love him so much you can probably expect to see him in Patapon 2."[3]

Patapon 2 was developed by Pyramid and produced by Japan Studio.[4] Game designer Hiroyuki Kotani began the development of Patapon 2 during the localization development of its predecessor. During this time, he was approached by producer Junichi Yoshizawa to create a multiplayer version of Patapon.[5] Initially Kotani disapproved multiplayer but would regret not adding it in the original version after seeing an online bulletin criticizing the lack of multiplayer.[6] In addition to multiplayer, Kotani received requests for Patapon to have more customization and longer gameplay time.[6][7] Kotani also noted the complaints of its predecessor being too difficult and aimed at making the sequel easier but also have enough features so that it isn't considered Patapon 1.5.[8] The bird-riding Toripons introduced in Patapon 2 were initially planned for its predecessor, Patapon.[9] Kemmei Adachi returns as the composer for the game and would write down Kotani's instructions after they both finished surfing together.[9] The voices for Patapon and the enemies were voiced by a child under the alias "Blico".[9] Adachi would create a demo of the song and show it to Blico to sing it.[9]

A demo was shown in GDC 2009 with keychain and plush prototype merchandise.[10]The Plush was released officially by Medicom Toy in December 2008.[11] Patapon 2 was released on November 27, 2008 alongside a limited edition PSP 3000 bundle, titled Patapon 2 Don Chaka Winter Gift Pack.[b][12]

It was later released in North America on May 9, 2009 in digital format only via PlayStation Store as a test case to determine consumer preferences.[13][14] A flash minigame titled, Patapon 2: Art of War was developed by Kerb to promote Patapon 2. It was hosted on SPIL Games from March 9 to March 16, 2009.[15] The game was later ported on PlayStation 4 on January 30, 2020 under the title, Patapon 2 Remastered.[16][17]

By the first week of release, Patapon 2 was ranked #1 top-selling PSP game of North America.[31] Famitsu inducted the game onto their Gold Hall of Fame.[21] IGN awarded the game for "Best Action Game" and for "PSP Game of the Year".[32][33]

Multiple reviewers questioned whether Patapon 2 fit the definition of a "sequel". PlayStation Official Magazine – Australia initially compared it to downloadable content, reporting that the game continues directly where its predecessor ended and doesn't make any changes to the core gameplay. However, concluded the review describing it as a true sequel, and having little to criticize.[28] PlayStation Official Magazine – UK also noted that the game was similar to its predecessor but felt it was ludicrous to criticize the game for lack of originality.[27] IGN reported that the game was very similar to its predecessor, particularly in the beginning and ending but continued to state that the game was more than just Patapon 1.5.[26] GamePro's Heather Bartron called the game a "must-have title for PSP owners," praising it as an improved sequel to the already enjoyable and addictive Patapon. Bartron wrote that both titles have great visual style though Patapon 2 has limited multiplayer modes and "needs more songs."[23] Hyper's Tracey Lien commends the game for being "exactly the same as the first Patapon, which is good because the original was really rad".[34]

During the 13th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards, the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences nominated Patapon 2 for "Outstanding Achievement in Portable Game Design".[35]

Mercedes theme by Beast786 Download: Mercedes.p3t Mercedes may refer to:

TurboTime 1.1 theme by goggles182 Download: TurboTime1.1.p3t P3T Unpacker v0.12 This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit! Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip Instructions: Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme. The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract. The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following: Black theme by J-Rad14 Download: Black_2.p3t

Black is a color that results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey.[2] It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness.[3] Black and white have often been used to describe opposites such as good and evil, the Dark Ages versus Age of Enlightenment, and night versus day. Since the Middle Ages, black has been the symbolic color of solemnity and authority, and for this reason it is still commonly worn by judges and magistrates.[3]

Black was one of the first colors used by artists in Neolithic cave paintings.[4] It was used in ancient Egypt and Greece as the color of the underworld.[5] In the Roman Empire, it became the color of mourning, and over the centuries it was frequently associated with death, evil, witches, and magic.[6] In the 14th century, it was worn by royalty, clergy, judges, and government officials in much of Europe. It became the color worn by English romantic poets, businessmen and statesmen in the 19th century, and a high fashion color in the 20th century.[3] According to surveys in Europe and North America, it is the color most commonly associated with mourning, the end, secrets, magic, force, violence, fear, evil, and elegance.[7]

Black is the most common ink color used for printing books, newspapers and documents, as it provides the highest contrast with white paper and thus is the easiest color to read. Similarly, black text on a white screen is the most common format used on computer screens.[8] As of September 2019,[update] the darkest material is made by MIT engineers from vertically aligned carbon nanotubes.[9]

The word black comes from Old English blæc ("black, dark", also, "ink"), from Proto-Germanic *blakkaz ("burned"), from Proto-Indo-European *bhleg- ("to burn, gleam, shine, flash"), from base *bhel- ("to shine"), related to Old Saxon blak ("ink"), Old High German blach ("black"), Old Norse blakkr ("dark"), Dutch blaken ("to burn"), and Swedish bläck ("ink"). More distant cognates include Latin flagrare ("to blaze, glow, burn"), and Ancient Greek phlegein ("to burn, scorch"). The Ancient Greeks sometimes used the same word to name different colors, if they had the same intensity. Kuanos' could mean both dark blue and black.[10] The Ancient Romans had two words for black: ater was a flat, dull black, while niger was a brilliant, saturated black. Ater has vanished from the vocabulary, but niger was the source of the country name Nigeria,[11] the English word Negro, and the word for "black" in most modern Romance languages (French: noir; Spanish and Portuguese: negro; Italian: nero; Romanian: negru).

Old High German also had two words for black: swartz for dull black and blach for a luminous black. These are parallelled in Middle English by the terms swart for dull black and blaek for luminous black. Swart still survives as the word swarthy, while blaek became the modern English black.[10] The former is cognate with the words used for black in most modern Germanic languages aside from English (German: schwarz, Dutch: zwart, Swedish: svart, Danish: sort, Icelandic: svartr).[12] In heraldry, the word used for the black color is sable,[13] named for the black fur of the sable, an animal.

Black was one of the first colors used in art. The Lascaux Cave in France contains drawings of bulls and other animals drawn by paleolithic artists between 18,000 and 17,000 years ago. They began by using charcoal, and later achieved darker pigments by burning bones or grinding a powder of manganese oxide.[10]

For the ancient Egyptians, black had positive associations; being the color of fertility and the rich black soil flooded by the Nile. It was the color of Anubis, the god of the underworld, who took the form of a black jackal, and offered protection against evil to the dead. To ancient Greeks, black represented the underworld, separated from the living by the river Acheron, whose water ran black. Those who had committed the worst sins were sent to Tartarus, the deepest and darkest level. In the center was the palace of Hades, the king of the underworld, where he was seated upon a black ebony throne. Black was one of the most important colors used by ancient Greek artists. In the 6th century BC, they began making black-figure pottery and later red figure pottery, using a highly original technique. In black-figure pottery, the artist would paint figures with a glossy clay slip on a red clay pot. When the pot was fired, the figures painted with the slip would turn black, against a red background. Later they reversed the process, painting the spaces between the figures with slip. This created magnificent red figures against a glossy black background.[14]

In the social hierarchy of ancient Rome, purple was reserved for the emperor; red was the color worn by soldiers (red cloaks for the officers, red tunics for the soldiers); white the color worn by the priests, and black was worn by craftsmen and artisans. The black they wore was not deep and rich; the vegetable dyes used to make black were not solid or lasting, so the blacks often faded to gray or brown.[15]

In Latin, the word for black, ater and to darken, atere, were associated with cruelty, brutality and evil. They were the root of the English words "atrocious" and "atrocity".[16] For the Romans, black symbolized death and mourning. In the 2nd century BC Roman magistrates wore a dark toga, called a toga pulla, to funeral ceremonies. Later, under the Empire, the family of the deceased also wore dark colors for a long period; then, after a banquet to mark the end of mourning, exchanged the black for a white toga. In Roman poetry, death was called the hora nigra, the black hour.[10]

The German and Scandinavian peoples worshipped their own goddess of the night, Nótt, who crossed the sky in a chariot drawn by a black horse. They also feared Hel, the goddess of the kingdom of the dead, whose skin was black on one side and red on the other. They also held sacred the raven. They believed that Odin, the king of the Nordic pantheon, had two black ravens, Huginn and Muninn, who served as his agents, traveling the world for him, watching and listening.[17]

In the early Middle Ages, black was commonly associated with darkness and evil. In Medieval paintings, the devil was usually depicted as having human form, but with wings and black skin or hair.[18]

In fashion, black did not have the prestige of red, the color of the nobility. It was worn by Benedictine monks as a sign of humility and penitence. In the 12th century a famous theological dispute broke out between the Cistercian monks, who wore white, and the Benedictines, who wore black. A Benedictine abbot, Pierre the Venerable, accused the Cistercians of excessive pride in wearing white instead of black. Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, the founder of the Cistercians responded that black was the color of the devil, hell, "of death and sin", while white represented "purity, innocence and all the virtues".[19]

Black symbolized both power and secrecy in the medieval world. The emblem of the Holy Roman Empire of Germany was a black eagle. The black knight in the poetry of the Middle Ages was an enigmatic figure, hiding his identity, usually wrapped in secrecy.[20]

Black ink, invented in China, was traditionally used in the Middle Ages for writing, for the simple reason that black was the darkest color and therefore provided the greatest contrast with white paper or parchment, making it the easiest color to read. It became even more important in the 15th century, with the invention of printing. A new kind of ink, printer's ink, was created out of soot, turpentine and walnut oil. The new ink made it possible to spread ideas to a mass audience through printed books, and to popularize art through black and white prints. Because of its contrast and clarity, black ink on white paper continued to be the standard for printing books, newspapers and documents; and for the same reason black text on a white background is the most common format used on computer screens.[8]

In the early Middle Ages, princes, nobles and the wealthy usually wore bright colors, particularly scarlet cloaks from Italy. Black was rarely part of the wardrobe of a noble family. The one exception was the fur of the sable. This glossy black fur, from an animal of the marten family, was the finest and most expensive fur in Europe. It was imported from Russia and Poland and used to trim the robes and gowns of royalty.

In the 14th century, the status of black began to change. First, high-quality black dyes began to arrive on the market, allowing garments of a deep, rich black. Magistrates and government officials began to wear black robes, as a sign of the importance and seriousness of their positions. A third reason was the passage of sumptuary laws in some parts of Europe which prohibited the wearing of costly clothes and certain colors by anyone except members of the nobility. The famous bright scarlet cloaks from Venice and the peacock blue fabrics from Florence were restricted to the nobility. The wealthy bankers and merchants of northern Italy responded by changing to black robes and gowns, made with the most expensive fabrics.[21]