Blue theme by Ru$$

Download: Blue_2.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

| Blue | |

|---|---|

Clockwise, from top left: A Ukrainian Police officer on duty; Tiles of the Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque, Iran; Red-legged honeycreeper; Copper(II) sulfate; Sea at the Marshall Islands; Planet Earth. | |

| Spectral coordinates | |

| Wavelength | approx. 450–495 nm |

| Frequency | ~670–610 THz |

| Hex triplet | #0000FF |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (0, 0, 255) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (240°, 100%, 100%) |

| CIELChuv (L, C, h) | (32, 131, 266°) |

| Source | HTML/CSS[1] |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) H: Normalized to [0–100] (hundred) | |

Blue is one of the three primary colours in the RYB colour model (traditional colour theory), as well as in the RGB (additive) colour model.[2] It lies between violet and cyan on the spectrum of visible light. The term blue generally describes colours perceived by humans observing light with a dominant wavelength that’s between approximately 450 and 495 nanometres. Most blues contain a slight mixture of other colours; azure contains some green, while ultramarine contains some violet. The clear daytime sky and the deep sea appear blue because of an optical effect known as Rayleigh scattering. An optical effect called the Tyndall effect explains blue eyes. Distant objects appear more blue because of another optical effect called aerial perspective.

Blue has been an important colour in art and decoration since ancient times. The semi-precious stone lapis lazuli was used in ancient Egypt for jewellery and ornament and later, in the Renaissance, to make the pigment ultramarine, the most expensive of all pigments.[3] In the eighth century Chinese artists used cobalt blue to colour fine blue and white porcelain. In the Middle Ages, European artists used it in the windows of cathedrals. Europeans wore clothing coloured with the vegetable dye woad until it was replaced by the finer indigo from America. In the 19th century, synthetic blue dyes and pigments gradually replaced organic dyes and mineral pigments. Dark blue became a common colour for military uniforms and later, in the late 20th century, for business suits. Because blue has commonly been associated with harmony, it was chosen as the colour of the flags of the United Nations and the European Union.[4]

In the United States and Europe, blue is the colour that both men and women are most likely to choose as their favourite, with at least one recent survey showing the same across several other countries, including China, Malaysia, and Indonesia.[5][6] Past surveys in the US and Europe have found that blue is the colour most commonly associated with harmony, confidence, masculinity, knowledge, intelligence, calmness, distance, infinity, the imagination, cold, and sadness.[7]

Etymology and linguistics[edit]

The modern English word blue comes from Middle English bleu or blewe, from the Old French bleu, a word of Germanic origin, related to the Old High German word blao (meaning 'shimmering, lustrous').[8] In heraldry, the word azure is used for blue.[9]

In Russian, Spanish,[10] Mongolian, Irish, and some other languages, there is no single word for blue, but rather different words for light blue (голубой, goluboj; Celeste) and dark blue (синий, sinij; Azul) (see Colour term).

Several languages, including Japanese and Lakota Sioux, use the same word to describe blue and green. For example, in Vietnamese, the colour of both tree leaves and the sky is xanh. In Japanese, the word for blue (青, ao) is often used for colours that English speakers would refer to as green, such as the colour of a traffic signal meaning "go". In Lakota, the word tȟó is used for both blue and green, the two colours not being distinguished in older Lakota (for more on this subject, see Blue–green distinction in language).

Linguistic research indicates that languages do not begin by having a word for the colour blue.[11] Colour names often developed individually in natural languages, typically beginning with black and white (or dark and light), and then adding red, and only much later – usually as the last main category of colour accepted in a language – adding the colour blue, probably when blue pigments could be manufactured reliably in the culture using that language.[11]

Optics and colour theory[edit]

The term blue generally describes colours perceived by humans observing light with a dominant wavelength between approximately 450 and 495 nanometres.[12] Blues with a higher frequency and thus a shorter wavelength gradually look more violet, while those with a lower frequency and a longer wavelength gradually appear more green. Purer blues are in the middle of this range, e.g., around 470 nanometres.

Isaac Newton included blue as one of the seven colours in his first description of the visible spectrum.[13] He chose seven colours because that was the number of notes in the musical scale, which he believed was related to the optical spectrum. He included indigo, the hue between blue and violet, as one of the separate colours, though today it is usually considered a hue of blue.[14]

In painting and traditional colour theory, blue is one of the three primary colours of pigments (red, yellow, blue), which can be mixed to form a wide gamut of colours. Red and blue mixed together form violet, blue and yellow together form green. Mixing all three primary colours together produces a dark brown. From the Renaissance onward, painters used this system to create their colours (see RYB colour model).

The RYB model was used for colour printing by Jacob Christoph Le Blon as early as 1725. Later, printers discovered that more accurate colours could be created by using combinations of cyan, magenta, yellow, and black ink, put onto separate inked plates and then overlaid one at a time onto paper. This method could produce almost all the colours in the spectrum with reasonable accuracy.

-

Additive colour mixing. The combination of primary colours produces secondary colours where two overlap; the combination red, green, and blue each in full intensity makes white.

-

Red, green, and blue subpixels on a liquid-crystal display.

On the HSV colour wheel, the complement of blue is yellow; that is, a colour corresponding to an equal mixture of red and green light. On a colour wheel based on traditional colour theory (RYB) where blue was considered a primary colour, its complementary colour is considered to be orange (based on the Munsell colour wheel).[15]

LED[edit]

In 1993, high-brightness blue LEDs were demonstrated by Shuji Nakamura of Nichia Corporation.[16][17][18] In parallel, Isamu Akasaki and Hiroshi Amano of Nagoya University were working on a new development which revolutionized LED lighting.[19][20]

Nakamura was awarded the 2006 Millennium Technology Prize for his invention.[21] Nakamura, Hiroshi Amano and Isamu Akasaki were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2014 for the invention of an efficient blue LED.[22]

Lasers[edit]

Lasers emitting in the blue region of the spectrum became widely available to the public in 2010 with the release of inexpensive high-powered 445–447 nm laser diode technology.[23] Previously the blue wavelengths were accessible only through DPSS which are comparatively expensive and inefficient, but still widely used by scientists for applications including optogenetics, Raman spectroscopy, and particle image velocimetry, due to their superior beam quality.[24] Blue gas lasers are also still commonly used for holography, DNA sequencing, optical pumping, among other scientific and medical applications.

Shades and variations[edit]

Blue is the colour of light between violet and cyan on the visible spectrum. Hues of blue include indigo and ultramarine, closer to violet; pure blue, without any mixture of other colours; Azure, which is a lighter shade of blue, similar to the colour of the sky; Cyan, which is midway in the spectrum between blue and green, and the other blue-greens such as turquoise, teal, and aquamarine.

Blue also varies in shade or tint; darker shades of blue contain black or grey, while lighter tints contain white. Darker shades of blue include ultramarine, cobalt blue, navy blue, and Prussian blue; while lighter tints include sky blue, azure, and Egyptian blue (for a more complete list see the List of colours).

As a structural colour[edit]

In nature, many blue phenomena arise from structural colouration, the result of interference between reflections from two or more surfaces of thin films, combined with refraction as light enters and exits such films. The geometry then determines that at certain angles, the light reflected from both surfaces interferes constructively, while at other angles, the light interferes destructively. Diverse colours therefore appear despite the absence of colourants.[25]

Colourants[edit]

Artificial blues[edit]

Egyptian blue, the first artificial pigment, was produced in the third millennium BC in Ancient Egypt. It is produced by heating pulverized sand, copper, and natron. It was used in tomb paintings and funereal objects to protect the dead in their afterlife. Prior to the 1700s, blue colourants for artwork were mainly based on lapis lazuli and the related mineral ultramarine. A breakthrough occurred in 1709 when German druggist and pigment maker Johann Jacob Diesbach discovered Prussian blue. The new blue arose from experiments involving heating dried blood with iron sulphides and was initially called Berliner Blau. By 1710 it was being used by the French painter Antoine Watteau, and later his successor Nicolas Lancret. It became immensely popular for the manufacture of wallpaper, and in the 19th century was widely used by French impressionist painters.[26] Beginning in the 1820s, Prussian blue was imported into Japan through the port of Nagasaki. It was called bero-ai, or Berlin blue, and it became popular because it did not fade like traditional Japanese blue pigment, ai-gami, made from the dayflower. Prussian blue was used by both Hokusai, in his wave paintings, and Hiroshige.[27]

In 1799 a French chemist, Louis Jacques Thénard, made a synthetic cobalt blue pigment which became immensely popular with painters.

In 1824 the Societé pour l'Encouragement d'Industrie in France offered a prize for the invention of an artificial ultramarine which could rival the natural colour made from lapis lazuli. The prize was won in 1826 by a chemist named Jean Baptiste Guimet, but he refused to reveal the formula of his colour. In 1828, another scientist, Christian Gmelin then a professor of chemistry in Tübingen, found the process and published his formula. This was the beginning of new industry to manufacture artificial ultramarine, which eventually almost completely replaced the natural product.[28]

In 1878 German chemists synthesized indigo. This product rapidly replaced natural indigo, wiping out vast farms growing indigo. It is now the blue of blue jeans. As the pace of organic chemistry accelerated, a succession of synthetic blue dyes were discovered including Indanthrone blue, which had even greater resistance to fading during washing or in the sun, and copper phthalocyanine.

-

The Blue Boy (1770), featuring lapis lazuli, indigo, and cobalt colourants,[29]

-

The Great Wave off Kanagawa illustrates the use of Prussian blue

-

A synthetic indigo dye factory in Germany in 1890.

Dyes for textiles and food[edit]

Blue dyes are organic compounds, both synthetic and natural.[30] Woad and true indigo were once used but since the early 1900s, all indigo is synthetic. Produced on an industrial scale, indigo is the blue of blue jeans.

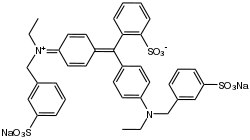

For food, the triarylmethane dye Brilliant blue FCF is used for candies. The search continues for stable, natural blue dyes suitable for the food industry.[30]

Pigments for painting and glass[edit]

Blue pigments were once produced from minerals, especially lapis lazuli and its close relative ultramarine. These minerals were crushed, ground into powder, and then mixed with a quick-drying binding agent, such as egg yolk (tempera painting); or with a slow-drying oil, such as linseed oil, for oil painting. Two inorganic but synthetic blue pigments are cerulean blue (primarily cobalt(II) stanate: Co2SnO4) and Prussian blue (milori blue: primarily Fe7(CN)18). The chromophore in blue glass and glazes is cobalt(II). Diverse cobalt(II) salts such as cobalt carbonate or cobalt(II) aluminate are mixed with the silica prior to firing. The cobalt occupies sites otherwise filled with silicon.

Inks[edit]

Methyl blue is the dominant blue pigment in inks used in pens.[31] Blueprinting involves the production of Prussian blue in situ.

![Prussian blue, FeIII 4[FeII (CN) 6] 3, is the blue of blueprints.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b2/Prussian_blue.jpg/684px-Prussian_blue.jpg)

![The Blue Boy (1770), featuring lapis lazuli, indigo, and cobalt colourants,[29]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/b/b6/The_Blue_Boy.jpg/203px-The_Blue_Boy.jpg)