Dragon theme by Chtijeremie

Download: Dragon.p3t

(1 background)

A dragon is a magical legendary creature that appears in the folklore of multiple cultures worldwide. Beliefs about dragons vary considerably through regions, but dragons in Western cultures since the High Middle Ages have often been depicted as winged, horned, and capable of breathing fire. Dragons in eastern cultures are usually depicted as wingless, four-legged, serpentine creatures with above-average intelligence. Commonalities between dragons' traits are often a hybridization of feline, reptilian, mammalian, and avian features. Some scholars believe large extinct or migrating crocodiles bear the closest resemblance, especially when encountered in forested or swampy areas, and are most likely the template of modern Asian dragon imagery.[1][2]

Etymology[edit]

The word dragon entered the English language in the early 13th century from Old French dragon, which, in turn, comes from the Latin: draco (genitive draconis) meaning "huge serpent, dragon", from Ancient Greek δράκων, drákōn (genitive δράκοντος, drákontos) "serpent".[4][5] The Greek and Latin term referred to any great serpent, not necessarily mythological.[6] The Greek word δράκων is most likely derived from the Greek verb δέρκομαι (dérkomai) meaning "I see", the aorist form of which is ἔδρακον (édrakon).[5] This is thought to have referred to something with a "deadly glance",[7] or unusually bright[8] or "sharp"[9][10] eyes, or because a snake's eyes appear to be always open; each eye actually sees through a big transparent scale in its eyelids, which are permanently shut. The Greek word probably derives from an Indo-European base *derḱ- meaning "to see"; the Sanskrit root दृश् (dr̥ś-) also means "to see".[11]

Historic tales and records[edit]

Draconic creatures appear in virtually all cultures around the globe[12] and the earliest attested reports of draconic creatures resemble giant snakes. Draconic creatures are first described in the mythologies of the ancient Near East and appear in ancient Mesopotamian art and literature. Stories about storm-gods slaying giant serpents occur throughout nearly all Near Eastern and Indo-European mythologies. Famous prototypical draconic creatures include the mušḫuššu of ancient Mesopotamia; Apep in Egyptian mythology; Vṛtra in the Rigveda; the Leviathan in the Hebrew Bible; Grand'Goule in the Poitou region in France; Python, Ladon, Wyvern and the Lernaean Hydra in Greek mythology; Kulshedra in Albanian Mythology; Unhcegila in Lakota mythology; Jörmungandr, Níðhöggr, and Fafnir in Norse mythology; the dragon from Beowulf; and aži and az in ancient Persian mythology, closely related to another mythological figure, called Aži Dahaka or Zahhak.

Nonetheless, scholars dispute where the idea of a dragon originates from[13] and a wide variety of hypotheses have been proposed.[13]

In his book An Instinct for Dragons (2000), David E. Jones (anthropologist) suggests a hypothesis that humans, like monkeys, have inherited instinctive reactions to snakes, large cats, and birds of prey.[14] He cites a study which found that approximately 39 people in a hundred are afraid of snakes[15] and notes that fear of snakes is especially prominent in children, even in areas where snakes are rare.[15] The earliest attested dragons all resemble snakes or have snakelike attributes.[16] Jones therefore concludes that dragons appear in nearly all cultures because humans have an innate fear of snakes and other animals that were major predators of humans' primate ancestors.[17] Dragons are usually said to reside in "dark caves, deep pools, wild mountain reaches, sea bottoms, haunted forests", all places which would have been fraught with danger for early human ancestors.[18]

In her book The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman Times (2000), Adrienne Mayor argues that some stories of dragons may have been inspired by ancient discoveries of fossils belonging to dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals.[19] She argues that the dragon lore of northern India may have been inspired by "observations of oversized, extraordinary bones in the fossilbeds of the Siwalik Hills below the Himalayas"[20] and that ancient Greek artistic depictions of the Monster of Troy may have been influenced by fossils of Samotherium, an extinct species of giraffe whose fossils are common in the Mediterranean region.[20] In China, a region where fossils of large prehistoric animals are common, these remains are frequently identified as "dragon bones"[21] and are commonly used in traditional Chinese medicine.[21] Mayor, however, is careful to point out that not all stories of dragons and giants are inspired by fossils[21] and notes that Scandinavia has many stories of dragons and sea monsters, but has long "been considered barren of large fossils."[21] In one of her later books, she states that, "Many dragon images around the world were based on folk knowledge or exaggerations of living reptiles, such as Komodo dragons, Gila monsters, iguanas, alligators, or, in California, alligator lizards, though this still fails to account for the Scandinavian legends, as no such animals (historical or otherwise) have ever been found in this region."[22]

Robert Blust in The Origin of Dragons (2000) argues that, like many other creations of traditional cultures, dragons are largely explicable as products of a convergence of rational pre-scientific speculation about the world of real events. In this case, the event is the natural mechanism governing rainfall and drought, with particular attention paid to the phenomenon of the rainbow.[23]

African stories/records[edit]

Egypt[edit]

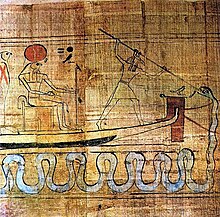

In Egyptian mythology, Apep or Apophis is a giant serpentine creature who resides in the Duat, the Egyptian Underworld.[24][25] The Bremner-Rhind papyrus, written around 310 BC, preserves an account of a much older Egyptian tradition that the setting of the sun is caused by Ra descending to the Duat to battle Apep.[24][25] In some accounts, Apep is as long as the height of eight men with a head made of flint.[25] Thunderstorms and earthquakes were thought to be caused by Apep's roar[26] and solar eclipses were thought to be the result of Apep attacking Ra during the daytime.[26] In some myths, Apep is slain by the god Set.[27] Nehebkau is another giant serpent who guards the Duat and aided Ra in his battle against Apep.[26] Nehebkau was so massive in some stories that the entire earth was believed to rest atop his coils.[26] Denwen is a giant serpent mentioned in the Pyramid Texts whose body was made of fire and who ignited a conflagration that nearly destroyed all the gods of the Egyptian pantheon.[28] He was ultimately defeated by the Pharaoh, a victory which affirmed the Pharaoh's divine right to rule.[29]

The ouroboros was a well-known Egyptian symbol of a serpent swallowing its own tail.[30] The precursor to the ouroboros was the "Many-Faced",[30] a serpent with five heads, who, according to the Amduat, the oldest surviving Book of the Afterlife, was said to coil around the corpse of the sun god Ra protectively.[30] The earliest surviving depiction of a "true" ouroboros comes from the gilded shrines in the tomb of Tutankhamun.[30] In the early centuries AD, the ouroboros was adopted as a symbol by Gnostic Christians[31] and chapter 136 of the Pistis Sophia, an early Gnostic text, describes "a great dragon whose tail is in its mouth".[31] In medieval alchemy, the ouroboros became a typical western dragon with wings, legs, and a tail.[30] A famous image of the dragon gnawing on its tail from the eleventh-century Codex Marcianus was copied in numerous works on alchemy.[30]

Asian stories/records[edit]

West Asia[edit]

Mesopotamia[edit]

Ancient people across the Near East believed in creatures similar to what modern people call "dragons".[33] These ancient people were unaware of the existence of dinosaurs or similar creatures in the distant past.[33] References to dragons of both benevolent and malevolent characters occur throughout ancient Mesopotamian literature.[33] In Sumerian poetry, great kings are often compared to the ušumgal, a gigantic, serpentine monster.[33] A draconic creature with the foreparts of a lion and the hind-legs, tail, and wings of a bird appears in Mesopotamian artwork from the Akkadian Period (c. 2334 – 2154 BC) until the Neo-Babylonian Period (626 BC–539 BC).[34] The dragon is usually shown with its mouth open.[34] It may have been known as the (ūmu) nā’iru, which means "roaring weather beast",[34] and may have been associated with the god Ishkur (Hadad).[34] A slightly different lion-dragon with two horns and the tail of a scorpion appears in art from the Neo-Assyrian Period (911 BC–609 BC).[34] A relief probably commissioned by Sennacherib shows the gods Ashur, Sin, and Adad standing on its back.[34]

Another draconic creature with horns, the body and neck of a snake, the forelegs of a lion, and the hind-legs of a bird appears in Mesopotamian art from the Akkadian Period until the Hellenistic Period (323 BC–31 BC).[32] This creature, known in Akkadian as the mušḫuššu, meaning "furious serpent", was used as a symbol for particular deities and also as a general protective emblem.[32] It seems to have originally been the attendant of the Underworld god Ninazu,[32] but later became the attendant to the Hurrian storm-god Tishpak, as well as, later, Ninazu's son Ningishzida, the Babylonian national god Marduk, the scribal god Nabu, and the Assyrian national god Ashur.[32]

Scholars disagree regarding the appearance of Tiamat, the Babylonian goddess personifying primeval chaos, slain by Marduk in the Babylonian creation epic Enûma Eliš.[35][36] She was traditionally regarded by scholars as having had the form of a giant serpent,[36] but several scholars have pointed out that this shape "cannot be imputed to Tiamat with certainty"[36] and she seems to have at least sometimes been regarded as anthropomorphic.[35][36] Nonetheless, in some texts, she seems to be described with horns, a tail, and a hide that no weapon can penetrate,[35] all features which suggest she was conceived as some form of dragoness.[35]

Levant[edit]

In the mythologies of the Ugarit region, specifically the Baal Cycle from the Ugaritic texts, the sea-dragon Lōtanu is described as "the twisting serpent / the powerful one with seven heads."[37] In KTU 1.5 I 2–3, Lōtanu is slain by the storm-god Baal,[37] but, in KTU 1.3 III 41–42, he is instead slain by the virgin warrior goddess Anat.[37]

In the Hebrew Bible, in the Book of Psalms, Psalm 74, Psalm 74:13–14, the sea-dragon Leviathan, is slain by Yahweh, god of the kingdoms of Israel and Judah, as part of the creation of the world.[37][38] In Isaiah 27:1, Yahweh's destruction of Leviathan is foretold as part of his impending overhaul of the universal order:[39][40]

| Original Hebrew text | English |

|---|---|

א בַּיּוֹם הַהוּא יִפְקֹד יְהוָה בְּחַרְבּוֹ הַקָּשָׁה וְהַגְּדוֹלָה וְהַחֲזָקָה, עַל לִוְיָתָן נָחָשׁ |

In that day the LORD will take |

| —Isaiah 27:1 |

Job 41:1–34 contains a detailed description of the Leviathan, who is described as being so powerful that only Yahweh can overcome it.[42] Job 41:19–21 states that the Leviathan exhales fire and smoke, making its identification as a mythical dragon clearly apparent.[42] In some parts of the Old Testament, the Leviathan is historicized as a symbol for the nations that stand against Yahweh.[38] Rahab, a synonym for "Leviathan", is used in several Biblical passages in reference to Egypt.[38] Isaiah 30:7 declares: "For Egypt's help is worthless and empty, therefore I have called her 'the silenced Rahab'."[38] Similarly, Psalm 87:3 reads: "I reckon Rahab and Babylon as those that know me..."[38] In Ezekiel 29:3–5 and Ezekiel 32:2–8, the pharaoh of Egypt is described as a "dragon" (tannîn).[38] In the story of Bel and the Dragon from the Book of Daniel, the prophet Daniel sees a dragon being worshipped by the Babylonians.[43] Daniel makes "cakes of pitch, fat, and hair";[43] the dragon eats them and bursts open.[44][43]

Ancient and Post-classical[edit]

Iran/Persia[edit]

Azhi Dahaka (Avestan Great Snake) is a dragon or demonic figure in the texts and mythology of Zoroastrian Persia, where he is one of the subordinates of Angra Mainyu. Alternate names include Azi Dahak, Dahaka, and Dahak. Aži (nominative ažiš) is the Avestan word for "serpent" or "dragon.[45] The Avestan term Aži Dahāka and the Middle Persian azdahāg are the sources of the Middle Persian Manichaean demon of greed "Az", Old Armenian mythological figure Aždahak, Modern Persian 'aždehâ/aždahâ', Tajik Persian 'azhdahâ', Urdu 'azhdahā' (اژدها), as well as the Kurdish ejdîha (ئەژدیها). The name also migrated to Eastern Europe, assumed the form "azhdaja" and the meaning "dragon", "dragoness" or "water snake" in the Balkanic and Slavic languages.[46][47][48]

Despite the negative aspect of Aži Dahāka in mythology, dragons have been used on some banners of war throughout the history of Iranian peoples.

The Azhdarchid group of pterosaurs are named from a Persian word for "dragon" that ultimately comes from Aži Dahāka.

- In Zoroastrian literature

Aži Dahāka is the most significant and long-lasting of the ažis of the Avesta, the earliest religious texts of Zoroastrianism. He is described as a monster with three mouths, six eyes, and three heads, and as being cunning, strong, and demonic. In other respects, Aži Dahāka has human qualities, and is never a mere animal. In a post-Avestan Zoroastrian text, the Dēnkard, Aži Dahāka is possessed of all possible sins and evil counsels, the opposite of the good king Jam (or Jamshid). The name Dahāg (Dahāka) is punningly interpreted as meaning "having ten (dah) sins".

In Persian Sufi literature, Rumi writes in his Masnavi[49] that the dragon symbolizes the sensual soul (nafs), greed and lust, that need to be mortified in a spiritual battle.[50][51]

In Ferdowsi's Shahnameh, the Iranian hero Rostam must slay an 80-meter-long dragon (which renders itself invisible to human sight) with the aid of his legendary horse, Rakhsh. As Rostam is sleeping, the dragon approaches; Rakhsh attempts to wake Rostam, but fails to alert him to the danger until Rostam sees the dragon. Rakhsh bites the dragon, while Rostam decapitates it. This is the third trial of Rostam's Seven Labors.[52][53][54]

Rostam is also credited with the slaughter of other dragons in the Shahnameh and in other Iranian oral traditions, notably in the myth of Babr-e-Bayan. In this tale, Rostam is still an adolescent and kills a dragon in the "Orient" (either India or China, depending on the source) by forcing it to swallow either ox hides filled with quicklime and stones or poisoned blades. The dragon swallows these foreign objects and its stomach bursts, after which Rostam flays the dragon and fashions a coat from its hide called the babr-e bayān. In some variants of the story, Rostam then remains unconscious for two days and nights, but is guarded by his steed Rakhsh. On reviving, he washes himself in a spring. In the Mandean tradition of the story, Rostam hides in a box, is swallowed by the dragon, and kills it from inside its belly. The king of China then gives Rostam his daughter in marriage as a reward.[55][56]

East Asia[edit]

China[edit]