Superman theme by Elvis

Download: Superman_4.p3t

(1 background, different for HD and SD)

| Clark Kent / Kal-El Superman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | DC Comics |

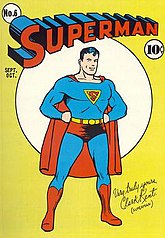

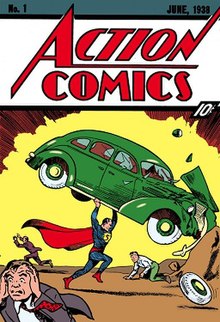

| First appearance | Action Comics #1 (cover-dated June 1938; published April 18, 1938) |

| Created by | Jerry Siegel (writer) Joe Shuster (artist) |

| In-story information | |

| Alter ego | Kal-El (birth name) Clark J. Kent (adopted name) |

| Species | Kryptonian |

| Place of origin | Krypton |

| Team affiliations | |

| Partnerships |

|

| Notable aliases |

|

| Abilities |

|

Superman is a superhero who appears in American comic books published by DC Comics. The character was created by writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster, and debuted in the comic book Action Comics #1 (cover-dated June 1938 and published April 18, 1938).[1] Superman has been adapted to a number of other media, which includes radio serials, novels, films, television shows, theater, and video games.

Superman was born on the fictional planet Krypton with the birth name of Kal-El. As a baby, his parents sent him to Earth in a small spaceship shortly before Krypton was destroyed in a natural cataclysm. His ship landed in the American countryside near the fictional town of Smallville, Kansas. He was found and adopted by farmers Jonathan and Martha Kent, who named him Clark Kent. Clark began developing various superhuman abilities, such as incredible strength and impervious skin. His adoptive parents advised him to use his powers for the benefit of humanity, and he decided to fight crime as a vigilante. To protect his personal life, he changes into a colorful costume and uses the alias "Superman" when fighting crime. Clark resides in the fictional American city of Metropolis, where he works as a journalist for the Daily Planet. Superman's supporting characters include his love interest and fellow journalist Lois Lane, Daily Planet photographer Jimmy Olsen, and editor-in-chief Perry White, and his enemies include Brainiac, General Zod, and archenemy Lex Luthor.

Superman is the archetype of the superhero: he wears an outlandish costume, uses a codename, and fights evil with the aid of extraordinary abilities. Although there are earlier characters who arguably fit this definition, it was Superman who popularized the superhero genre and established its conventions. He was the best-selling superhero in American comic books up until the 1980s.[2]

Development[edit]

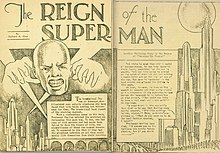

Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster met in 1932 while attending Glenville High School in Cleveland and bonded over their admiration of fiction. Siegel aspired to become a writer and Shuster aspired to become an illustrator. Siegel wrote amateur science fiction stories, which he self-published as a magazine called Science Fiction: The Advance Guard of Future Civilization. His friend Shuster often provided illustrations for his work.[3] In January 1933, Siegel published a short story in his magazine titled "The Reign of the Superman". The titular character is a homeless man named Bill Dunn who is tricked by an evil scientist into consuming an experimental drug. The drug gives Dunn the powers of mind-reading, mind-control, and clairvoyance. He uses these powers maliciously for profit and amusement, but then the drug wears off, leaving him a powerless vagrant again. Shuster provided illustrations, depicting Dunn as a bald man.[4]

Siegel and Shuster shifted to making comic strips, with a focus on adventure and comedy. They wanted to become syndicated newspaper strip authors, so they showed their ideas to various newspaper editors. However, the newspaper editors told them that their ideas were insufficiently sensational. If they wanted to make a successful comic strip, it had to be something more sensational than anything else on the market. This prompted Siegel to revisit Superman as a comic strip character.[5][6] Siegel modified Superman's powers to make him even more sensational: Like Bill Dunn, the second prototype of Superman is given powers against his will by an unscrupulous scientist, but instead of psychic abilities, he acquires superhuman strength and bullet-proof skin.[7][8] Additionally, this new Superman was a crime-fighting hero instead of a villain, because Siegel noted that comic strips with heroic protagonists tended to be more successful.[9] In later years, Siegel once recalled that this Superman wore a "bat-like" cape in some panels, but typically he and Shuster agreed there was no costume yet, and there is none apparent in the surviving artwork.[10][11]

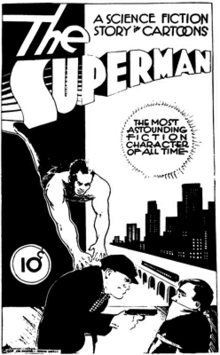

Siegel and Shuster showed this second concept of Superman to Consolidated Book Publishers, based in Chicago.[12][a] In May 1933, Consolidated had published a proto-comic book titled Detective Dan: Secret Operative 48.[13] It contained all-original stories as opposed to reprints of newspaper strips, which was a novelty at the time.[14] Siegel and Shuster put together a comic book in a similar format called The Superman. A delegation from Consolidated visited Cleveland that summer on a business trip and Siegel and Shuster took the opportunity to present their work in person.[15][16] Although Consolidated expressed interest, they later pulled out of the comics business without ever offering a book deal because the sales of Detective Dan were disappointing.[17][18]

Siegel believed publishers kept rejecting them because he and Shuster were young and unknown, so he looked for an established artist to replace Shuster.[19] When Siegel told Shuster what he was doing, Shuster reacted by burning their rejected Superman comic, sparing only the cover. They continued collaborating on other projects, but for the time being Shuster was through with Superman.[20]

Siegel wrote to numerous artists.[19] The first response came in July 1933 from Leo O'Mealia, who drew the Fu Manchu strip for the Bell Syndicate.[21][22] In the script that Siegel sent to O'Mealia, Superman's origin story changes: He is a "scientist-adventurer" from the far future when humanity has naturally evolved "superpowers". Just before the Earth explodes, he escapes in a time-machine to the modern era, whereupon he immediately begins using his superpowers to fight crime.[23] O'Mealia produced a few strips and showed them to his newspaper syndicate, but they were rejected. O'Mealia did not send to Siegel any copies of his strips, and they have been lost.[24]

In June 1934, Siegel found another partner: an artist in Chicago named Russell Keaton.[25][26] Keaton drew the Buck Rogers and Skyroads comic strips. In the script that Siegel sent Keaton in June, Superman's origin story further evolved: In the distant future, when Earth is on the verge of exploding due to "giant cataclysms", the last surviving man sends his three-year-old son back in time to the year 1935. The time-machine appears on a road where it is discovered by motorists Sam and Molly Kent. They leave the boy in an orphanage, but the staff struggle to control him because he has superhuman strength and impenetrable skin. The Kents adopt the boy and name him Clark, and teach him that he must use his fantastic natural gifts for the benefit of humanity. In November, Siegel sent Keaton an extension of his script: an adventure where Superman foils a conspiracy to kidnap a star football player. The extended script mentions that Clark puts on a special "uniform" when assuming the identity of Superman, but it is not described.[27] Keaton produced two weeks' worth of strips based on Siegel's script. In November, Keaton showed his strips to a newspaper syndicate, but they too were rejected, and he abandoned the project.[28][29]

Siegel and Shuster reconciled and resumed developing Superman together. The character became an alien from the planet Krypton. Shuster designed the now-familiar costume: tights with an "S" on the chest, over-shorts, and a cape.[30][31][32] They made Clark Kent a journalist who pretends to be timid, and conceived his colleague Lois Lane, who is attracted to the bold and mighty Superman but does not realize that he and Kent are the same person.[33]

In June 1935 Siegel and Shuster finally found work with National Allied Publications, a comic magazine publishing company in New York owned by Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson.[35] Wheeler-Nicholson published two of their strips in New Fun Comics #6 (1935): "Henri Duval" and "Doctor Occult".[36] Siegel and Shuster also showed him Superman and asked him to market Superman to the newspapers on their behalf.[37] In October, Wheeler-Nicholson offered to publish Superman in one of his own magazines.[38] Siegel and Shuster refused his offer because Wheeler-Nicholson had demonstrated himself to be an irresponsible businessman. He had been slow to respond to their letters and had not paid them for their work in New Fun Comics #6. They chose to keep marketing Superman to newspaper syndicates themselves.[39][40] Despite the erratic pay, Siegel and Shuster kept working for Wheeler-Nicholson because he was the only publisher who was buying their work, and over the years they produced other adventure strips for his magazines.[41]

Wheeler-Nicholson's financial difficulties continued to mount. In 1936, he formed a joint corporation with Harry Donenfeld and Jack Liebowitz called Detective Comics, Inc. in order to release his third magazine, which was titled Detective Comics. Siegel and Shuster produced stories for Detective Comics too, such as "Slam Bradley". Wheeler-Nicholson fell into deep debt to Donenfeld and Liebowitz, and in early January 1938, Donenfeld and Liebowitz petitioned Wheeler-Nicholson's company into bankruptcy and seized it.[3][42]

In early December 1937, Siegel visited Liebowitz in New York, and Liebowitz asked Siegel to produce some comics for an upcoming comic anthology magazine called Action Comics.[43][44] Siegel proposed some new stories, but not Superman. Siegel and Shuster were, at the time, negotiating a deal with the McClure Newspaper Syndicate for Superman. In early January 1938, Siegel had a three-way telephone conversation with Liebowitz and an employee of McClure named Max Gaines. Gaines informed Siegel that McClure had rejected Superman, and asked if he could forward their Superman strips to Liebowitz so that Liebowitz could consider them for Action Comics. Siegel agreed.[45] Liebowitz and his colleagues were impressed by the strips, and they asked Siegel and Shuster to develop the strips into 13 pages for Action Comics.[46] Having grown tired of rejections, Siegel and Shuster accepted the offer. At least now they would see Superman published.[47][48] Siegel and Shuster submitted their work in late February and were paid $130 (equivalent to $2,814 in 2023) for their work ($10 per page).[49] In early March they signed a contract at Liebowitz's request in which they gave away the copyright for Superman to Detective Comics, Inc. This was normal practice in the business, and Siegel and Shuster had given away the copyrights to their previous works as well.[50]

The duo's revised version of Superman appeared in the first issue of Action Comics, which was published on April 18, 1938. The issue was a huge success thanks to Superman's feature.[1][51][52]

Influences[edit]

Siegel and Shuster read pulp science-fiction and adventure magazines, and many stories featured characters with fantastical abilities such as telepathy, clairvoyance, and superhuman strength. One character in particular was John Carter of Mars from the novels by Edgar Rice Burroughs. John Carter is a human who is transported to Mars, where the lower gravity makes him stronger than the natives and allows him to leap great distances.[53][54] Another influence was Philip Wylie's 1930 novel Gladiator, featuring a protagonist named Hugo Danner who had similar powers.[55][56]

Superman's stance and devil-may-care attitude were influenced by the characters of Douglas Fairbanks, who starred in adventure films such as The Mark of Zorro and Robin Hood.[57] The name of Superman's home city, Metropolis, was taken from the 1927 film of the same name.[58] Popeye cartoons were also an influence.[58]

Clark Kent's harmless facade and dual identity were inspired by the protagonists of such movies as Don Diego de la Vega in The Mark of Zorro and Sir Percy Blakeney in The Scarlet Pimpernel. Siegel thought this would make for interesting dramatic contrast and good humor.[59][60] Another inspiration was slapstick comedian Harold Lloyd. The archetypal Lloyd character was a mild-mannered man who finds himself abused by bullies but later in the story snaps and fights back furiously.[61]

Kent is a journalist because Siegel often imagined himself becoming one after leaving school. The love triangle between Lois Lane, Clark, and Superman was inspired by Siegel's own awkwardness with girls.[62]

The pair collected comic strips in their youth, with a favorite being Winsor McCay's fantastical Little Nemo.[58] Shuster remarked on the artists who played an important part in the development of his own style: "Alex Raymond and Burne Hogarth were my idols – also Milt Caniff, Hal Foster, and Roy Crane."[58] Shuster taught himself to draw by tracing over the art in the strips and magazines they collected.[3]

As a boy, Shuster was interested in fitness culture[63] and a fan of strongmen such as Siegmund Breitbart and Joseph Greenstein. He collected fitness magazines and manuals and used their photographs as visual references for his art.[3]

The visual design of Superman came from multiple influences. The tight-fitting suit and shorts were inspired by the costumes of wrestlers, boxers, and strongmen. In early concept art, Shuster gave Superman laced sandals like those of strongmen and classical heroes, but these were eventually changed to red boots.[34] The costumes of Douglas Fairbanks were also an influence.[64] The emblem on his chest was inspired by heraldic crests.[65] Many pulp action heroes such as swashbucklers wore capes. Superman's face was based on Johnny Weissmuller with touches derived from the comic-strip character Dick Tracy and from the work of cartoonist Roy Crane.[66]

The word "superman" was commonly used in the 1920s and 1930s to describe men of great ability, most often athletes and politicians.[67] It occasionally appeared in pulp fiction stories as well, such as "The Superman of Dr. Jukes".[68] It is unclear whether Siegel and Shuster were influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche's concept of the Übermensch; they never acknowledged as much.[69]

Comics[edit]

Comic books[edit]

Since 1938, Superman stories have been regularly published in periodical comic books published by DC Comics. The first and oldest of these is Action Comics, which began in April 1938.[1] Action Comics was initially an anthology magazine, but it eventually became dedicated to Superman stories. The second oldest periodical is Superman, which began in June 1939. Action Comics and Superman have been published without interruption (ignoring changes to the title and numbering scheme).[71][72] A number of other shorter-lived Superman periodicals have been published over the years.[73] Superman is part of the DC Universe, which is a shared setting of superhero characters owned by DC Comics, and consequently he frequently appears in stories alongside the likes of Batman, Wonder Woman, and others.

Superman has sold more comic books over his publication history than any other American superhero character.[74] Exact sales figures for the early decades of Superman comic books are hard to find because, like most publishers at the time, DC Comics concealed this data from its competitors and thereby the general public as well, but given the general market trends at the time, sales of Action Comics and Superman probably peaked in the mid-1940s and thereafter steadily declined.[75] Sales data first became public in 1960, and showed that Superman was the best-selling comic book character of the 1960s and 1970s.[2][76][77] Sales rose again starting in 1987. Superman #75 (Nov 1992) sold over 23 million copies,[78] making it the best-selling issue of a comic book of all time, thanks to a media sensation over the supposedly permanent death of the character in that issue.[79] Sales declined from that point on. In March 2018, Action Comics sold just 51,534 copies, although such low figures are normal for superhero comic books in general (for comparison, Amazing Spider-Man #797 sold only 128,189 copies).[80] The comic books are today considered a niche aspect of the Superman franchise due to low readership,[81] though they remain influential as creative engines for the movies and television shows. Comic book stories can be produced quickly and cheaply, and are thus an ideal medium for experimentation.[82]

Whereas comic books in the 1950s were read by children, since the 1990s the average reader has been an adult.[83] A major reason for this shift was DC Comics' decision in the 1970s to sell its comic books to specialty stores instead of traditional magazine retailers (supermarkets, newsstands, etc.) — a model called "direct distribution". This made comic books less accessible to children.[84]

Newspaper strips[edit]

Beginning in January 1939, a Superman daily comic strip appeared in newspapers, syndicated through the McClure Syndicate. A color Sunday version was added that November. Jerry Siegel wrote most of the strips until he was conscripted in 1943. The Sunday strips had a narrative continuity separate from the daily strips, possibly because Siegel had to delegate the Sunday strips to ghostwriters.[85] By 1941, the newspaper strips had an estimated readership of 20 million.[86] Joe Shuster drew the early strips, then passed the job to Wayne Boring.[87] From 1949 to 1956, the newspaper strips were drawn by Win Mortimer.[88] The strip ended in May 1966, but was revived from 1977 to 1983 to coincide with a series of movies released by Warner Bros.[89]

Editors[edit]

Initially, Siegel was allowed to write Superman more or less as he saw fit because nobody had anticipated the success and rapid expansion of the franchise.[90][91] But soon Siegel and Shuster's work was put under careful oversight for fear of trouble with censors.[92] Siegel was forced to tone down the violence and social crusading that characterized his early stories.[93] Editor Whitney Ellsworth, hired in 1940, dictated that Superman not kill.[94] Sexuality was banned, and colorfully outlandish villains such as Ultra-Humanite and Toyman were thought to be less nightmarish for young readers.[95]

Mort Weisinger was the editor on Superman comics from 1941 to 1970, his tenure briefly interrupted by military service. Siegel and his fellow writers had developed the character with little thought of building a coherent mythology, but as the number of Superman titles and the pool of writers grew, Weisinger demanded a more disciplined approach.[96] Weisinger assigned story ideas, and the logic of Superman's powers, his origin, the locales, and his relationships with his growing cast of supporting characters were carefully planned. Elements such as Bizarro, his cousin Supergirl, the Phantom Zone, the Fortress of Solitude, alternate varieties of kryptonite, robot doppelgangers, and Krypto were introduced during this era. The complicated universe built under Weisinger was beguiling to devoted readers but alienating to casuals.[97] Weisinger favored lighthearted stories over serious drama, and avoided sensitive subjects such as the Vietnam War and the American civil rights movement because he feared his right-wing views would alienate his left-leaning writers and readers.[98] Weisinger also introduced letters columns in 1958 to encourage feedback and build intimacy with readers.[99]

Weisinger retired in 1970 and Julius Schwartz took over. By his own admission, Weisinger had grown out of touch with newer readers.[100] Starting with The Sandman Saga, Schwartz updated Superman by making Clark Kent a television anchor, and he retired overused plot elements such as kryptonite and robot doppelgangers.[101] Schwartz also scaled Superman's powers down to a level closer to Siegel's original. These changes would eventually be reversed by later writers. Schwartz allowed stories with serious drama such as "For the Man Who Has Everything" (Superman Annual #11), in which the villain Mongul torments Superman with an illusion of happy family life on a living Krypton.

Schwartz retired from DC Comics in 1986 and was succeeded by Mike Carlin as an editor on Superman comics. His retirement coincided with DC Comics' decision to reboot the DC Universe with the companywide-crossover storyline "Crisis on Infinite Earths". In The Man of Steel writer John Byrne rewrote the Superman mythos, again reducing Superman's powers, which writers had slowly re-strengthened, and revised many supporting characters, such as making Lex Luthor a billionaire industrialist rather than a mad scientist, and making Supergirl an artificial shapeshifting organism because DC wanted Superman to be the sole surviving Kryptonian.

Carlin was promoted to Executive Editor for the DC Universe books in 1996, a position he held until 2002. K.C. Carlson took his place as editor of the Superman comics.

Aesthetic style[edit]

In the earlier decades of Superman comics, artists were expected to conform to a certain "house style".[102] Joe Shuster defined the

Beast

Beast theme by unknown

Download: Beast.p3t

(2 backgrounds)

Beast most often refers to:

Beast or Beasts may also refer to:

Bible[edit]

- Beast (Revelation), two beasts described in the Book of Revelation

Computing and gaming[edit]

- Beast (card game), English name of historical French game, the first card game to use bidding

- BEAST (computer security), a computer security attack

- BEAST (music composition), a music composition and modular synthesis application that runs under Unix

- Beast (lighting software), a computer-graphics lighting software

- Beast (Trojan horse), a Windows-based backdoor trojan horse

- Beast (video game), a 1984 ASCII game

Film and television[edit]

- Beast, from the fairy tale Beauty and the Beast

- Beast (Disney character), a character from the 1991 animated film Beauty and the Beast and sequels

- Beast (2017 film), a British psychological thriller

- Beast (2022 American film), an American thriller film directed by Baltasar Kormákur and starring Idris Elba

- Beast (2022 Indian film), an Indian Tamil-language film

- Beast (TV series), a 2000–2001 British sitcom

- Beasts (TV series), a 1976 British horror programme by Nigel Kneale

- Beast, a minor character in the television series Angel

- Beast, a villain from the television series Doctor Who

- Beast, a television series character from Law & Order: Criminal Intent (season 4)

- Beast, stage name of professional wrestler Matt Morgan in American Gladiators

- Beast, a character in the television series Maggie and the Ferocious Beast

- Beast Man, a character in the cartoon He-Man and the Masters of the Universe

- Beastly, a character from the Care Bears franchise

- Beastur, a character in the animated television series My Pet Monster

- Kamen Rider Beast, a character in Kamen Rider Wizard

Literature[edit]

- Beast (Marvel Comics), a Marvel Comics character

- Beast (Benchley novel), a 1991 novel by Peter Benchley

- Beast (Kennen novel), a 2006 novel by Ally Kennen

- Beasts (Crowley novel), a 1976 novel by John Crowley

- Beasts (novella), a 2001 novella by Joyce Carol Oates

- Beast, a 2000 novel by Donna Jo Napoli

- Beast, a graphic novel by Marian Churchland, winner of the 2010 Russ Manning Award

Music[edit]

Film soundtrack[edit]

- Beast (soundtrack), soundtrack album of the film of the 2022 Tamil-language film Beast

- Beast (score), 2022 film score of the 2022 Tamil-language film Beast

Groups[edit]

Albums[edit]

- Beast (Beast album) (2008)

- Beast (DevilDriver album) (2011)

- Beast (Magic Dirt album) (2007)

- Beast (Vamps album) (2010)

- Beast (V.I.C. album) (2008)

Songs[edit]

- "Beast" (Chipmunk song) (2008)

- "Beast" (Mia Martina song) (2015)

- "Beast" (Nico Vega song) (2006 EP version, 2013 single)

- "Beast", by Brymo from 9: Harmattan & Winter (2021)

- "Beast", by Jolin Tsai from Muse (2012)

- "Beast (Southpaw Remix)", by Rob Bailey & The Hustle Standard from the film soundtrack Southpaw (2015)

Other[edit]

- Birmingham ElectroAcoustic Sound Theatre, a sound diffusion system

Other uses[edit]

- Beast (Alton Towers), a roller coaster at Alton Towers, Staffordshire, England

- Beast Lake, a lake in Minnesota, US

- Bengaluru Beast, an Indian basketball team

- Benjamin Butler (politician) (1813–1893), American politician and Governor of Massachusetts, American Civil War Union Army general nicknamed "Beast Butler"

- L.A. Beast, the nickname of competitive eater Kevin Strahle

- Beast (street artist), a contemporary artist from Italy, who produces public artworks of a political nature

- Presidential state car (United States), the state car of the President of the United States, nicknamed "The Beast”

- Cyberbeast, brand-name of the tri-motor, all-wheel drive variant of the Tesla Cybertruck

See also[edit]

- All pages with titles containing beast

- All pages with titles containing bestial

- Beastie (disambiguation)

- Bestial (album), a 1982 album by Barrabás

- The Beast (disambiguation)

- Beast Beast, a 2020 coming-of-age drama film

- The Beastmaster, a 1982 sword and sorcery film

Dark

Dark theme by Rume79

Download: Dark.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

Redirect to:

This page is a redirect. The following categories are used to track and monitor this redirect:

|

Scottie Pippen

Scottie Pippen theme by Logic

Download: ScottiePippen.p3t

(1 background)

Scotty Maurice Pippen Sr.[3][4] (born September 25, 1965), usually spelled Scottie Pippen, is an American former professional basketball player. He played 17 seasons in the National Basketball Association (NBA), winning six NBA championships with the Chicago Bulls. Considered one of the greatest small forwards of all time, Pippen played an important role in transforming the Bulls into a championship team and popularizing the NBA around the world during the 1990s.[5]

Pippen was named to the NBA All-Defensive First Team eight consecutive times and the All-NBA First Team three times. He was a seven-time NBA All-Star and was the NBA All-Star Game MVP in 1994. He was named one of the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History during the 1996–97 season, and is one of four players to have his jersey retired by the Chicago Bulls (the others being Jerry Sloan, Bob Love, and Michael Jordan). He played a main role on both the 1992 Chicago Bulls Championship team and the 1996 Chicago Bulls Championship team, which were selected as two of the Top 10 Teams in NBA History. His biography on the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame's website states that "the multidimensional Pippen ran the court like a point guard, attacked the boards like a power forward, and swished the nets like a shooting guard."[6] During his 17-year career, he played 12 seasons with the Bulls, one with the Houston Rockets and four with the Portland Trail Blazers, making the postseason 16 consecutive times. In October 2021, Pippen was again honored as one of the league’s greatest players of all time by being named to the NBA 75th Anniversary Team.[7]

Pippen is the only NBA player to have won an NBA title and Olympic gold medal in the same year twice, having done so in both 1992 and 1996.[8] He was a part of the 1992 U.S. Olympic "Dream Team" which beat its opponents by an average of 44 points.[9] He was also a key figure in the 1996 Olympic team, alongside former "Dream Team" members Karl Malone, John Stockton, Charles Barkley, and David Robinson, as well as newer faces such as Shaquille O'Neal, Anfernee "Penny" Hardaway and Grant Hill. He wore the number 8 during both years.

Pippen is a two-time inductee into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, once for his individual career and once as a member of the "Dream Team", having been simultaneously inducted for both on August 13, 2010.[10] The Bulls retired his number 33 on December 8, 2005. The University of Central Arkansas retired his number 33 on January 21, 2010.[11]

He was formerly married to television personality Larsa Pippen, and is the father of basketball player Scotty Pippen Jr.

Early life[edit]

Pippen was born in Hamburg, Arkansas, to Ethel (1923–2016)[12] and Preston Pippen (1920–1990).[13] He has 11 older siblings. His mother was 6 ft (180 cm) tall and his father was 6 ft 1 in (185 cm), and all of their children were tall, with Scottie Pippen being the tallest. His parents could not afford to send their other children to college. His father worked in a paper mill until suffering from a stroke that paralyzed his right side, prevented him from walking, and affected his speech.[14] Pippen attended Hamburg High School. Playing point guard, he led his team to the state playoffs and earned all-conference honors as a senior, but was not offered any college scholarships.

College career[edit]

Pippen began his college playing career at the University of Central Arkansas after being discovered by the school's head basketball coach, Don Dyer, as a walk-on. He did not receive much media coverage because Central Arkansas played in the NAIA, while the media focused on the more prestigious NCAA. Pippen stood only 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m) tall when he graduated from high school, but experienced a growth spurt while at Central Arkansas and grew to 6 ft 8 in (2.03 m).[15] As a senior, his per game averages of 23.6 points, 10 rebounds, 4.3 assists, and near 60 percent field goal shooting earned him consensus NAIA All-American honors in 1986 and 1987, making him a dominant player in the Arkansas Intercollegiate Conference, drawing the attention of NBA scouts.[11][16]

Professional career[edit]

Chicago Bulls (1987–1998)[edit]

Early career (1987–1990)[edit]

Having eyed Pippen before the 1987 NBA draft,[17] the Chicago Bulls manufactured a trade with the Seattle SuperSonics that sent Pippen, selected fifth overall, to the Bulls in exchange for the eighth pick, Olden Polynice, and future draft pick options.[18] Pippen became part of Chicago's young forward duo with 6-foot-10-inch (208 cm) power forward Horace Grant (the 10th overall pick in 1987), although both came off the bench during their rookie seasons. Pippen made his NBA debut on November 7, 1987, when the Chicago Bulls opened against the Philadelphia 76ers. He finished with 10 points, two steals, four assists, and one rebound in 23 minutes of play, and the Bulls won 104–94.[19]

With teammate Michael Jordan as a motivational and instructional mentor, Pippen refined his skills and slowly developed many new ones over his career. Jordan and Pippen frequently played one-on-one outside of team practices, simply to hone each other's skills on offense and defense. Pippen claimed the starting small forward position during the 1988 NBA Playoffs, helping the Jordan-led Bulls to reach the conference semifinals for the first time in over a decade. Pippen emerged as one of the league's premier young forwards at the turn of the decade,[20][failed verification] recording then-career highs in points (16.5 points per game), rebounds (6.7 rebounds per game), and field goal shooting (48.9%), as well as finishing third in the league in steals with 211 during the 1989-1990 season.[1] These feats earned Pippen his debut NBA All-Star selection in 1990.[21]

Pippen continued to improve[citation needed] as the Bulls reached the Eastern Conference Finals in 1989 and 1990. In each season, the Bulls were eliminated by the Detroit Pistons.[22] In the 1990 Eastern Conference Finals, Pippen suffered a severe migraine headache at the start of Game Seven that impacted his play, and he made only one of his ten field goal attempts as the Bulls lost 93–74.[23]

The Bulls' first three-peat (1991–1993)[edit]

In the 1990–91 NBA season, Pippen emerged as the Bulls' primary defensive stopper and a versatile scoring threat in Phil Jackson's triangle offense. Alongside the help of Jordan, Pippen continued to improve his game, especially in shooting from the field.[24][better source needed] He had his first triple-double on November 23 when the Bulls faced the Los Angeles Clippers as he had 13 points, 12 assists and 13 rebounds in 30 minutes in a 105–97 win.[25] The Bulls finished the season with a record of 61–21. They were first in the Central Division, first in the Eastern Conference and second overall, as the Portland Trail Blazers clinched the first spot. Pippen was second on the team in points per game with 17.8 and steals with 2.4 next to Jordan and he was also second in rebounds per game with 7.3 next to Horace Grant. Pippen led the team in blocks per game with 1.1 and assists per game with 6.2.[26] He ranked fifth overall in the NBA in steals, both for total steals and steals per game.[27] For his efforts in the 1990–91 NBA season Pippen was awarded NBA All-Defensive Second Team honors.[26] The Bulls went on to defeat the Los Angeles Lakers in the 1991 NBA Finals.

Pippen helped lead the Bulls to their first three-peat, as they won the following two years in 1992 and 1993.

Pippen without Jordan (1993–1995)[edit]

Michael Jordan retired before the 1993–94 season and in his absence Pippen emerged from Jordan's shadow. That year, he earned All-Star Game MVP honors and led the Bulls in scoring, assists, and blocks, and was second in the NBA in steals per game, averaging 22.0 points, 8.7 rebounds, 5.6 assists, 2.9 steals, and 0.8 blocks per game, while shooting 49.1% from the field and a career-best 32% from the 3-point line. For his efforts, he earned the first of three straight All-NBA First Team selections, and he finished third in MVP voting. The Bulls (with key additions of Toni Kukoč, Steve Kerr and Luc Longley) finished the season with 55 wins, only two fewer than the year before.

However, one of the most controversial moments of Pippen's career came in his first year without Jordan. In the 1994 NBA Playoffs, the Eastern Conference Semifinals pitted the Bulls against the New York Knicks, whom the Bulls had dispatched en route to a championship each of the previous three seasons. On May 13, 1994, down 2–0 in the series in Game 3, Bulls coach Phil Jackson needed a big play from his team to have any chance of going on to the conference finals. With 1.8 seconds left and the score tied at 102, Jackson designed the last play for Toni Kukoč, with Pippen instructed to inbound the basketball. Pippen, who had been the Bulls' leader all season long in Jordan's absence, was so angered by Jackson's decision to not let him take the potential game-winner that he refused to leave the bench and re-enter the game when the timeout was over.[28] Although Kukoč did hit the game-winner, a 23-foot (7 m) fadeaway jumper at the buzzer, there was little celebrating by the Bulls, as television cameras caught an unsmiling Phil Jackson storming off the court.[29] "Scottie asked out of the play," Jackson told reporters moments later in the post-game interview.[30]

A key play occurred in Game 5 which changed the outcome of the series. With 2.1 seconds left in the fourth quarter, the Knicks' Hubert Davis attempted a 23-foot (7 m) shot which was defended by Pippen, who was called for a personal foul by referee Hue Hollins, who determined that Pippen made contact with Davis.[31] Television replays indicated that contact was made after Davis had released the ball.[31] Davis successfully made both free throw attempts to assist in the Knicks victory, 87–86, and gave the Knicks a three games to two advantage in the series.[31] The resulting incident was described as the most controversial moment of Hollins' career by Referee magazine.[32] Hollins defended the call after the game saying, "I saw Scottie make contact with his shooting motion. I'm positive there was contact on the shot."[31] Darell Garretson, the league's supervisor of officials and who also officiated in the league, agreed with Hollins and issued a statement, "The perception is that referees should put their whistles in their pockets in the last minutes. But it all comes down to what is sufficient contact. There's an old, old adage that refs don't make those calls in the last seconds. Obviously, you hope you don't make a call that will decide a game. But the call was within the context of how we had been calling them all game."[31] Garretson later changed his stance of the call the next season. Speaking to a Chicago Tribune reporter, Garretson described Hollins' call as "terrible".[32] Chicago head coach Phil Jackson, upset over the outcome of the game, was fined $10,000 for comparing the loss to the gold medal game controversy at the 1972 Summer Olympics.[33]

In Game 6, Pippen made the signature play of his career. Midway in the third quarter, Pippen received the ball during a Bulls fast break, charging toward the basket. As center Patrick Ewing jumped up to defend the shot, Pippen fully extended the ball out, absorbing body contact and a foul from Ewing, and slammed the ball through the hoop with Ewing's hand in his face. Pippen landed several feet away from the basket along the baseline, incidentally walking over a fallen Ewing. He then made taunting remarks to both Ewing and then Spike Lee, who was standing courtside supporting the Knicks, thus receiving a technical foul. This extended the Bulls' lead to 17; they won 93–79.

In Game 7, Pippen scored 20 points and grabbed 16 rebounds, but the Bulls still lost 87–77.[34] The Knicks then proceeded to the NBA Finals, where they lost to the Houston Rockets, also in seven games.

Trade rumors involving Pippen escalated during the 1994 off-season. Jerry Krause, the Bulls' general manager, was reportedly looking to ship Pippen off to the Seattle SuperSonics in exchange for all-star forward Shawn Kemp, moving Toni Kukoč into Pippen's position as starting small forward with Kemp filling in the vacant starting power forward position in place of Horace Grant, a free agent who left the Bulls for the up-and-coming Orlando Magic during the off-season. In January, when asked by Craig Sager as to whether he thought that he would be traded, Pippen replied, "I hope I am".[35] However, Pippen would remain a Bull and those rumors were put to rest once it was announced that Michael Jordan would be returning to the Bulls, late in the 1994–95 season. Badly lacking interior defense and rebounding due to Grant's departure, the Pippen-led Bulls did not play as well in the 1994 season as they had in the season before. For the first time in years, they were in danger of missing the playoffs. The Bulls were just 34–31, prior to Jordan's return for the final 17 games, and Jordan led them to a 13–4 record to close the regular season. Still, Pippen finished the 1994 season leading the Bulls in every major statistical category—points, rebounds, assists, steals, and blocks—joining Dave Cowens (1977–78) as the only players in NBA history to accomplish the feat; Kevin Garnett (2002–03), LeBron James (2008–09), Giannis Antetokounmpo (2016–17) and Nikola Jokić (2021–22) have since matched it.[5][36]

The Bulls' second three-peat (1996–1998)[edit]

With the return of Michael Jordan and the addition of multiple-time NBA rebound leader Dennis Rodman, the Bulls posted the best regular-season record in NBA history at the time (72–10) in 1995–96 (later surpassed in 2015–16 by the Golden State Warriors) en route to winning their fourth title against the Seattle SuperSonics. Later that year, Pippen became the first person to win an NBA championship and an Olympic gold medal in the same year twice, playing for Team USA at the Atlanta Olympics.[8]

The Bulls opened the 1996–97 NBA season with a 17–1 record and had a league-best record of 42–6 when entering the All-Star break.[37] In November 1996, Pippen set the NBA single-month plus-minus record of 272.[38] Both Pippen and Jordan were selected among the 50 Greatest Players in NBA History as part of the league celebrating its 50th season. The ceremony was held at half-time of the 1997 NBA All-Star Game, which took place on February 9, 1997. Phil Jackson, the Bulls' head coach, was honored as one of the 10 greatest coaches in NBA history, while the 1992 Chicago Bulls Championship team and the 1996 Chicago Bulls Championship team, on which Pippen had played a key role, were selected as two of the Top 10 Teams in NBA History.[39] In the All-Star game itself, Pippen was 4–9 from the field, finishing with 8 points as well as 3 rebounds and 2 assists in 25 minutes of play. The East defeat the West 132–120 and Glen Rice was crowned the All-Star Game MVP.[40]

Pippen scored a career high of 47 points in a 134–123 win over the Denver Nuggets on February 18, going 19–27 from the field and adding 4 rebounds, 5 assists, and 2 steals in 41 minutes of play.[41] On February 23 Pippen was voted "Player of The Week" for the week of February 17,[42] his fifth and final time to receive that honor. As the league entered its final weeks the Bulls lost several of their key players, including Bill Wennington (ruptured tendon in his foot),[43] Dennis Rodman (injured knee),[44] and Toni Kukoč (inflamed sole on his foot).[45] Pippen and Jordan were forced to shoulder a greater load while keeping the team headed towards a playoff appearance.[37] Even with this challenge Chicago finished a league-best 69–13 record. In the final game of the regular season, Pippen missed a game-winning 3-pointer, leaving the Bulls just short of having an NBA record-setting back-to-back 70-win seasons.[46] For his efforts in the 1996–97 NBA season, Pippen earned NBA All-Defensive First Team honors for the seventh consecutive time as well as All-NBA Second Team honors.[47]

Big 3

Rainbow Six Vegas 2 Official

Rainbow Six Vegas 2 Official theme by Ubisoft

Download: Rainbow6Vegas2Official.p3t

(1 background)

P3T Unpacker v0.12

Copyright (c) 2007. Anoop Menon

This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit!

Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip

Instructions:

Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme.

The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract.

The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename].

For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following:

p3textractor filename.p3t [destination path]Replace filename with the name of the p3t file, and replace [destination path] with the name of the folder you want the files to be extracted to. A destination path is not required. By default it will extract to extracted.filename.

Dark Sector Official

Dark Sector Official theme by D3 Publisher

Download: DarkSectorOfficial.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

P3T Unpacker v0.12

Copyright (c) 2007. Anoop Menon

This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit!

Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip

Instructions:

Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme.

The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract.

The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename].

For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following:

p3textractor filename.p3t [destination path]Replace filename with the name of the p3t file, and replace [destination path] with the name of the folder you want the files to be extracted to. A destination path is not required. By default it will extract to extracted.filename.

Haze Official EUR Version

Haze Official EUR Version theme by Ubisoft

Download: HazeOfficialEUR.p3t

(1 background)

P3T Unpacker v0.12

Copyright (c) 2007. Anoop Menon

This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit!

Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip

Instructions:

Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme.

The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract.

The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename].

For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following:

p3textractor filename.p3t [destination path]Replace filename with the name of the p3t file, and replace [destination path] with the name of the folder you want the files to be extracted to. A destination path is not required. By default it will extract to extracted.filename.

Hot Girls

Hot Girls theme by Trevor

Download: HotGirls.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

| "Hot Girls" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by Lil' Mo featuring Lil Wayne | ||||

| from the album Syndicated: The Lil' Mo Hour | ||||

| Released | November 9, 2004[1] | |||

| Recorded | Cutting Room (New York City, New York) | |||

| Genre | R&B, hip hop | |||

| Length | 3:52 | |||

| Label | Cash Money/Universal/Roun'table Entertainment | |||

| Songwriter(s) | C. Loving, D. Carter, B. Cox | |||

| Producer(s) | Bryan-Michael Cox | |||

| Lil' Mo singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Lil Wayne singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

"Hot Girls," also known as its alternate title "Hot Boys, Hot Girls," is a R&B and hip hop song recorded by American recording artist Lil' Mo for her unreleased album, Syndicated: The Lil' Mo Hour (2005).[2] The song features guest vocals by former labelmate Lil Wayne and production by frequent collaborator Bryan-Michael Cox. A remix for the single featuring Fabolous was released on DJ Envy's mixtape, Ahead of the Game: The Final Chapter.[3]

Critical reception[edit]

In spite of the buzz garnered from Lil' Mo's record deal with Cash Money, reception for the song was generally mixed to negative. Critics felt that the song was an "insecure female anthem," due to Mo's recitation of "I'm not Britney, I'm not Jessica, I'm not Mýa but I'm still on fire."[4] Many were also appalled by Mo's verse: "...Mine don't look like yours but I still got it going on," where critics believed Mo was further solidifying her point of feeling some sort of insecurity or jealousy.[4] Others also did not take too likely of Lil Wayne's guest appearance either, where they felt he was "rapping like Jay-Z again."[4] By contrast, Jermy Leeuwis of Music Remedy complimented the single as "sizzling" and praised Lil Wayne's feature as "precocious."[5]

Formats and track listings[edit]

- iTunes download[1]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Hot Girls" (Radio Version. Featuring Lil Wayne.) | 3:52 |

| 2. | "Hot Girls" (Radio Version - No Rap) | 3:21 |

- 12" vinyl[6]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Hot Girls" (Radio Version) | 3:51 |

| 2. | "Hot Girls" (Radio Version No Rap) | 3:51 |

| 3. | "Hot Girls" (Instrumental) | 3:48 |

| 4. | "Hot Girls" (Acapella) | 3:50 |

| 5. | "Hot Girls" (TV Track) | 3:50 |

Charts[edit]

| Chart (2004) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Singles Sales[7] | 28 |

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Hot Girls - Single by Lil' Mo". iTunes. Apple.com. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ Mitchell, Gail. "Lil' Mo In Cash Money Till." Billboard. July 17, 2004: 20. Print.

- ^ "Ahead of the Game: The Final Chapter - DJ Envy > Overview". AllMusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ a b c "A/B Conversation > 'Hot Girls,' Lil' Mo, feat. Lil Wayne." Vibe. February 2005: 145. Print.

- ^ Leeuwis, Jermy (July 11, 2005). "Lil Mo released Syndicated (The Lil Mo Hour)". Music Remedy. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ "Lil Mo* Feat. Lil Wayne - Hot Girls (Vinyl) at Discogs". Discogs. Discogs.com. Retrieved May 23, 2013.

- ^ "Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Singles Sales – Issue Date: 2004-12-25". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved May 23, 2013.