Blade Runner theme by BladeRacer

Download: BladeRunner.p3t

(1 background)

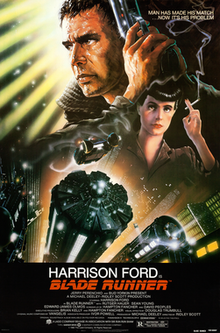

| Blade Runner | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by John Alvin | |

| Directed by | Ridley Scott |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? by Philip K. Dick |

| Produced by | Michael Deeley |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Jordan Cronenweth |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Vangelis |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. (worldwide) Shaw Brothers (Hong Kong) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 117 minutes[1] |

| Countries | United States[2][3] Hong Kong[4] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $30 million[5] |

| Box office | $41.8 million[6] |

Blade Runner is a 1982 science fiction film directed by Ridley Scott from a screenplay by Hampton Fancher and David Peoples.[7][8] Starring Harrison Ford, Rutger Hauer, Sean Young, and Edward James Olmos, it is an adaptation of Philip K. Dick's 1968 novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? The film is set in a dystopian future Los Angeles of 2019, in which synthetic humans known as replicants are bio-engineered by the powerful Tyrell Corporation to work on space colonies. When a fugitive group of advanced replicants led by Roy Batty (Hauer) escapes back to Earth, burnt-out cop Rick Deckard (Ford) reluctantly agrees to hunt them down.

Blade Runner initially underperformed in North American theaters and polarized critics; some praised its thematic complexity and visuals, while others critiqued its slow pacing and lack of action. The film's soundtrack, composed by Vangelis, was nominated in 1982 for a BAFTA and a Golden Globe as best original score. Blade Runner later became a cult film, and has since come to be regarded as one of the greatest science fiction films. Hailed for its production design depicting a high-tech but decaying future, the film is often regarded as both a leading example of neo-noir cinema and a foundational work of the cyberpunk[9] genre. It has influenced many science fiction films, video games, anime, and television series. It also brought the work of Dick to Hollywood's attention and led to several film adaptations of his works. In 1993, it was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress.

Seven different versions of Blade Runner exist as a result of controversial changes requested by studio executives. A director's cut was released in 1992 after a strong response to test screenings of a workprint. This, in conjunction with the film's popularity as a video rental, made it one of the earliest movies to be released on DVD. In 2007, Warner Bros. released The Final Cut, a 25th-anniversary digitally remastered version; this is the only version over which Scott retained artistic control.

The film is the first of the franchise of the same name. A sequel, titled Blade Runner 2049, was released in 2017 alongside a trilogy of short films covering the thirty-year span between the two films' settings. The anime series Blade Runner: Black Lotus was released in 2021.

Plot[edit]

In 2019 Los Angeles, former police officer Rick Deckard is detained by Officer Gaff, who likes to make origami figures, and is brought to his former supervisor, Bryant. Deckard, whose job as a "blade runner" was to track down bioengineered humanoids known as replicants and terminally "retire" them, is informed that four replicants are on Earth illegally. Deckard begins to leave, but Bryant ambiguously threatens him and Deckard stays. The two watch a video of a blade runner named Holden administering the Voight-Kampff test, which is designed to distinguish replicants from humans based on their emotional responses to questions. The test subject, Leon, shoots Holden on the second question. Bryant wants Deckard to retire Leon and three other Nexus-6 replicants: Roy Batty, Zhora, and Pris.

Bryant has Deckard meet with the CEO of the company that creates the replicants, Eldon Tyrell, so he can administer the test on a Nexus-6 to see if it works. Tyrell expresses his interest in seeing the test fail first and asks him to administer it on his assistant Rachael. After a much longer than standard test, Deckard concludes privately to Tyrell that Rachael is a replicant who believes she is human. Tyrell explains that she is an experiment who has been given false memories to provide an "emotional cushion", and that she has no knowledge of her true nature.

In searching Leon's hotel room, Deckard finds photos and a scale from the skin of an animal, which is later identified as a synthetic snake scale. Deckard returns to his apartment where Rachael is waiting. She tries to prove her humanity by showing him a family photo, but Deckard reveals that her memories are implants from Tyrell's niece, and she leaves in tears.

Replicants Roy and Leon meanwhile investigate a replicant eye-manufacturing laboratory and learn of J. F. Sebastian, a gifted genetic designer who works closely with Tyrell. Pris locates Sebastian and manipulates him to gain his trust.

A photograph from Leon's apartment and the snake scale lead Deckard to a strip club, where Zhora works. After a confrontation and chase, Deckard kills Zhora. Bryant also orders him to retire Rachael, who has disappeared from the Tyrell Corporation. Deckard spots Rachael in a crowd, but he is ambushed by Leon, who knocks the gun out of Deckard's hand and beats him. As Leon is about to kill Deckard, Rachael saves him by using Deckard's gun to kill Leon. They return to Deckard's apartment and, during a discussion, he promises not to track her down. As Rachael abruptly tries to leave, Deckard restrains her and forces her to kiss him, and she ultimately relents. Deckard leaves Rachael at his apartment and departs to search for the remaining replicants.

Roy arrives at Sebastian's apartment and tells Pris that the other replicants are dead. Sebastian reveals that because of a genetic premature aging disorder, his life will be cut short, like the replicants that were built with a four-year lifespan. Roy uses Sebastian to gain entrance to Tyrell's penthouse. He demands more life from his maker, which Tyrell says is impossible. Roy confesses that he has done "questionable things" but Tyrell dismisses this, praising Roy's advanced design and accomplishments in his short life. Roy kisses Tyrell and then kills him by crushing his skull. Sebastian tries to flee and is later reported dead.[nb 1]

At Sebastian's apartment, Deckard is ambushed by Pris, but he kills her as Roy returns. Roy's body begins to fail as the end of his lifespan nears. He chases Deckard through the building and onto the roof. Deckard tries to jump onto another roof but is left hanging on the edge. Roy makes the jump with ease and, as Deckard's grip loosens, Roy hoists him onto the roof to save him. Before Roy dies, he laments that his memories "will be lost in time, like tears in rain". Gaff arrives to congratulate Deckard, also reminding him that Rachael will not live, but "then again, who does?" Deckard returns to his apartment to retrieve Rachael. While escorting her to the elevator, he notices a small origami unicorn on the floor. He recalls Gaff's words and departs with Rachael.

Cast[edit]

- Harrison Ford as Rick Deckard

- Rutger Hauer as Roy Batty

- Sean Young as Rachael

- Edward James Olmos as Gaff

- M. Emmet Walsh as Bryant

- Daryl Hannah as Pris

- William Sanderson as J.F. Sebastian

- Brion James as Leon Kowalski

- Joe Turkel as Eldon Tyrell

- Joanna Cassidy as Zhora Salome

- James Hong as Hannibal Chew

- Morgan Paull as Dave Holden

- Hy Pyke as Taffey Lewis

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Interest in adapting Philip K. Dick's novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? developed shortly after its 1968 publication. Director Martin Scorsese was interested in filming the novel, but never optioned it.[11] Producer Herb Jaffe optioned it in the early 1970s, but Dick was unimpressed with the screenplay written by Herb's son Robert, saying, "Jaffe's screenplay was so terribly done ... Robert flew down to Santa Ana to speak with me about the project. And the first thing I said to him when he got off the plane was, 'Shall I beat you up here at the airport, or shall I beat you up back at my apartment?'"[12]

The screenplay by Hampton Fancher was optioned in 1977.[13] Producer Michael Deeley became interested in Fancher's draft and convinced director Ridley Scott to film it. Scott had previously declined the project, but after leaving the slow production of Dune, wanted a faster-paced project to take his mind off his older brother's recent death.[14] He joined the project on February 21, 1980, and managed to push up the promised Filmways financing from US$13 million to $15 million. Fancher's script focused more on environmental issues and less on issues of humanity and religion, which are prominent in the novel, and Scott wanted changes. Fancher found a cinema treatment by William S. Burroughs for Alan E. Nourse's novel The Bladerunner (1974), titled Blade Runner (a movie).[nb 2] Scott liked the name, so Deeley obtained the rights to the titles.[15] Eventually, he hired David Peoples to rewrite the script and Fancher left the job over the issue on December 21, 1980, although he later returned to contribute additional rewrites.[16]

Having invested over $2.5 million in pre-production,[17] as the date of commencement of principal photography neared, Filmways withdrew financial backing. In ten days Deeley had secured $21.5 million in financing through a three-way deal between the Ladd Company (through Warner Bros.), the Hong Kong-based producer Sir Run Run Shaw and Tandem Productions.[18]

Dick became concerned that no one had informed him about the film's production, which added to his distrust of Hollywood.[19] After Dick criticized an early version of Fancher's script in an article written for the Los Angeles Select TV Guide, the studio sent Dick the Peoples rewrite.[20] Although Dick died shortly before the film's release, he was pleased with the rewritten script and with a 20-minute special effects test reel that was screened for him when he was invited to the studio. Despite his well-known skepticism of Hollywood in principle, Dick enthused to Scott that the world created for the film looked exactly as he had imagined it.[21] He said, "I saw a segment of Douglas Trumbull's special effects for Blade Runner on the KNBC news. I recognized it immediately. It was my own interior world. They caught it perfectly." He also approved of the film's script, saying, "After I finished reading the screenplay, I got the novel out and looked through it. The two reinforce each other so that someone who started with the novel would enjoy the movie and someone who started with the movie would enjoy the novel."[22] The motion picture was dedicated to Dick.[23] Principal photography of Blade Runner began on March 9, 1981, and ended four months later.[24]

In 1992, Ford revealed, "Blade Runner is not one of my favorite films. I tangled with Ridley."[25] Apart from friction with the director, Ford also disliked the voiceovers: "When we started shooting it had been tacitly agreed that the version of the film that we had agreed upon was the version without voiceover narration. It was a f**king [sic] nightmare. I thought that the film had worked without the narration. But now I was stuck re-creating that narration. And I was obliged to do the voiceovers for people that did not represent the director's interests."[26] "I went kicking and screaming to the studio to record it."[27] The narration monologs were written by an uncredited Roland Kibbee.[28]

In 2006, Scott was asked "Who's the biggest pain in the arse you've ever worked with?" He replied: "It's got to be Harrison ... he'll forgive me because now I get on with him. Now he's become charming. But he knows a lot, that's the problem. When we worked together it was my first film up and I was the new kid on the block. But we made a good movie."[29] Ford said of Scott in 2000: "I admire his work. We had a bad patch there, and I'm over it."[30] In 2006 Ford reflected on the production of the film saying: "What I remember more than anything else when I see Blade Runner is not the 50 nights of shooting in the rain, but the voiceover ... I was still obliged to work for these clowns that came in writing one bad voiceover after another."[31] Ridley Scott confirmed in the summer 2007 issue of Total Film that Harrison Ford contributed to the Blade Runner Special Edition DVD, and had already recorded his interviews. "Harrison's fully on board", said Scott.[32]

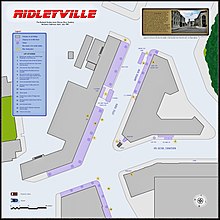

The Bradbury Building in downtown Los Angeles served as a filming location, and a Warner Bros. backlot housed the 2019 Los Angeles street sets. Other locations included the Ennis-Brown House and the 2nd Street Tunnel. Test screenings resulted in several changes, including adding a voice-over, a happy ending, and the removal of a Holden hospital scene. The relationship between the filmmakers and the investors was difficult, which culminated in Deeley and Scott being fired but still working on the film.[33] Crew members created T-shirts during filming saying, "Yes Guv'nor, My Ass" that mocked Scott's unfavorable comparison of U.S. and British crews; Scott responded with a T-shirt of his own, "Xenophobia Sucks", making the incident known as the T-shirt war.[34][35]

Casting[edit]

Casting the film proved troublesome, particularly for the lead role of Deckard. Screenwriter Hampton Fancher envisioned Robert Mitchum as Deckard and wrote the character's dialogue with Mitchum in mind.[36] Director Ridley Scott and the film's producers spent months meeting and discussing the role with Dustin Hoffman, who eventually departed over differences in vision.[36] Harrison Ford was ultimately chosen for several reasons, including his performance in the Star Wars films, Ford's interest in the Blade Runner story, and discussions with Steven Spielberg who was finishing Raiders of the Lost Ark at the time and strongly praised Ford's work in the film.[36] Following his success in those two films, Ford was looking for a role with dramatic depth.[26] According to production documents, several actors were considered for the role, including Gene Hackman, Sean Connery, Jack Nicholson, Paul Newman, Clint Eastwood, Tommy Lee Jones, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Peter Falk, Nick Nolte, Al Pacino and Burt Reynolds.[36][37]

One role that was not difficult to cast was Rutger Hauer as Roy Batty,[38] the violent yet thoughtful leader of the replicants.[39] Scott cast Hauer without having met him, based solely on Hauer's performances in Paul Verhoeven's movies Scott had seen (Katie Tippel, Soldier of Orange, and Turkish Delight).[36] Hauer's portrayal of Batty was regarded by Philip K. Dick as "the perfect Batty – cold, Aryan, flawless".[21] Of the many films Hauer made, Blade Runner was his favorite. As he explained in a live chat in 2001, "Blade Runner needs no explanation. It just [is]. All of the best. There is nothing like it. To be part of a real masterpiece which changed the world's thinking. It's awesome."[40] Hauer rewrote his character's "tears in rain" speech himself and presented the words to Scott on set prior to filming.

Blade Runner used a number of then-lesser-known actors: Sean Young portrays Rachael, an experimental replicant implanted with the memories of Tyrell's niece, causing her to believe she is human;[41] Nina Axelrod auditioned for the role.[36] Daryl Hannah portrays Pris, a "basic pleasure model" replicant; Stacey Nelkin auditioned for the role, but was given another part in the film, which was ultimately cut before filming.[36] Debbie Harry turned down the role of Pris.[42][43] Casting Pris and Rachael was challenging, requiring several screen tests with Morgan Paull playing the role of Deckard. Paull was cast as Deckard's fellow bounty hunter Holden based on his performances in the tests.[36] Brion James portrays Leon Kowalski, a combat and laborer replicant, and Joanna Cassidy portrays Zhora, an assassin replicant.

Edward James Olmos portrays Gaff. Olmos drew on diverse ethnic sources to help create the fictional "Cityspeak" language his character uses in the film.[44] His initial address to Deckard at the noodle bar is partly in Hungarian and means, "Horse dick [bullshit]! No way. You are the Blade ... Blade Runner."[44] M. Emmet Walsh portrays Captain Bryant, a rumpled, hard-drinking and underhanded police veteran typical of the film noir genre. Joe Turkel portrays Dr. Eldon Tyrell, a corporate mogul who built an empire on genetically manipulated humanoid slaves. William Sanderson was cast as J. F. Sebastian, a quiet and lonely genius who provides a compassionate yet compliant portrait of humanity. J. F. sympathizes with the replicants, whom he sees as companions,[45] and he shares their shorter lifespan due to his rapid aging disease.[46] Joe Pantoliano had earlier been considered for the role.[47] James Hong portrays Hannibal Chew, an elderly geneticist specializing in synthetic eyes, and Hy Pyke portrayed the sleazy bar owner Taffey Lewis – in a single take, something almost unheard-of with Scott, whose drive for perfection resulted at times in double-digit takes.[48]

Design[edit]

Scott credits Edward Hopper's painting Nighthawks and the French science fiction comics magazine Métal Hurlant, to which the artist Jean "Moebius" Giraud contributed, as stylistic mood sources.[49] He also drew on the landscape of "Hong Kong on a very bad day"[50] and the industrial landscape of his one-time home in northeast England.[51] The visual style of the movie is influenced by the work of futurist Italian architect Antonio Sant'Elia.[52] Scott hired Syd Mead as his concept artist; like Scott, he was influenced by Métal Hurlant.[53] Moebius was offered the opportunity to assist in the pre-production of Blade Runner, but he declined so that he could work on René Laloux's animated film Les Maîtres du temps – a decision that he later regretted.[54] Production designer Lawrence G. Paull and art director David Snyder realized Scott's and Mead's sketches. Douglas Trumbull and Richard Yuricich supervised the special effects for the film, and Mark Stetson served as chief model maker.[55]

Blade Runner has numerous similarities to Fritz Lang's Metropolis, including a built-up urban environment, in which the wealthy literally live above the workers, dominated by a huge building – the Stadtkrone Tower in Metropolis and the Tyrell Building in Blade Runner. Special effects supervisor David Dryer used stills from Metropolis when lining up Blade Runner's miniature building shots.[56]

The extended end scene in the original theatrical release shows Rachael and Deckard traveling into daylight with pastoral aerial shots filmed by director Stanley Kubrick. Ridley Scott contacted Kubrick about using some of his surplus helicopter aerial photography from The Shining.[57][58][59]

Spinner[edit]

"Spinner" is the generic term for the fictional flying cars used in the film. A spinner can be driven as a ground-based vehicle, and take off vertically, hover, and cruise much like vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) aircraft. They are used extensively by the police as patrol cars, and wealthy people can also acquire spinner licenses.[60] The vehicle was conceived and designed by Syd Mead who described the spinner as an aerodyne – a vehicle which directs air downward to create lift, though press kits for the film stated that the spinner was propelled by three engines: "conventional internal combustion, jet, and anti-gravity".[61] A spinner is on permanent exhibit at the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame in Seattle, Washington.[62] Mead's conceptual drawings were transformed into 25 vehicles by automobile customizer Gene Winfield; at least two were working ground vehicles, while others were light-weight mockups for crane shots and set decoration for street shots.[63] Two of them ended up at Disney World in Orlando, Florida, but were later destroyed, and a few others remain in private collections.[63]