Thor theme by myownscars

Download: Thor.p3t

(2 backgrounds)

Thor (from Old Norse: Þórr) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred groves and trees, strength, the protection of humankind, hallowing, and fertility. Besides Old Norse Þórr, the deity occurs in Old English as Þunor ("Thunor"), in Old Frisian as Thuner, in Old Saxon as Thunar, and in Old High German as Donar, all ultimately stemming from the Proto-Germanic theonym *Þun(a)raz, meaning 'Thunder'.

Thor is a prominently mentioned god throughout the recorded history of the Germanic peoples, from the Roman occupation of regions of Germania, to the Germanic expansions of the Migration Period, to his high popularity during the Viking Age, when, in the face of the process of the Christianization of Scandinavia, emblems of his hammer, Mjölnir, were worn and Norse pagan personal names containing the name of the god bear witness to his popularity.

Due to the nature of the Germanic corpus, narratives featuring Thor are only attested in Old Norse, where Thor appears throughout Norse mythology. Norse mythology, largely recorded in Iceland from traditional material stemming from Scandinavia, provides numerous tales featuring the god. In these sources, Thor bears at least fifteen names, and is the husband of the golden-haired goddess Sif and the lover of the jötunn Járnsaxa. With Sif, Thor fathered the goddess (and possible valkyrie) Þrúðr; with Járnsaxa, he fathered Magni; with a mother whose name is not recorded, he fathered Móði, and he is the stepfather of the god Ullr. Thor is the son of Odin and Jörð,[1] by way of his father Odin, he has numerous brothers, including Baldr. Thor has two servants, Þjálfi and Röskva, rides in a cart or chariot pulled by two goats, Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr (whom he eats and resurrects), and is ascribed three dwellings (Bilskirnir, Þrúðheimr, and Þrúðvangr). Thor wields the hammer Mjölnir, wears the belt Megingjörð and the iron gloves Járngreipr, and owns the staff Gríðarvölr. Thor's exploits, including his relentless slaughter of his foes and fierce battles with the monstrous serpent Jörmungandr—and their foretold mutual deaths during the events of Ragnarök—are recorded throughout sources for Norse mythology.

Into the modern period, Thor continued to be acknowledged in rural folklore throughout Germanic-speaking Europe. Thor is frequently referred to in place names, the day of the week Thursday bears his name (modern English Thursday derives from Old English þunresdæġ, 'Þunor's day'), and names stemming from the pagan period containing his own continue to be used today, particularly in Scandinavia. Thor has inspired numerous works of art and references to Thor appear in modern popular culture. Like other Germanic deities, veneration of Thor is revived in the modern period in Heathenry.

Name[edit]

The name Thor is derived from Norse mythology. Its medieval Germanic equivalents or cognates are Donar (Old High German), Þunor (Old English), Thuner (Old Frisian), Thunar (Old Saxon), and Þórr (Old Norse),[2] the latter of which inspired the form Thor. Though Old Norse Þórr has only one syllable, it too comes from an earlier, Proto-Norse two-syllable form which can be reconstructed as *Þunarr and/or *Þunurr (evidenced by the poems Hymiskviða and Þórsdrápa, and modern Elfdalian tųosdag 'Thursday'), through the common Old Norse development of the sequence -unr- to -ór-.[3]

All these forms of Thor's name descend from Proto-Germanic, but there is debate as to precisely what form the name took at that early stage. The form *Þunraz has been suggested[by whom?] and has the attraction of clearly containing the sequence -unr-, needed to explain the later form Þórr.[3]: 708 The form *Þunuraz is suggested by Elfdalian tųosdag ('Thursday') and by a runic inscription from around 700 from Hallbjäns in Sundre, Gotland, which includes the sequence "þunurþurus".[3]: 709–11 Finally, *Þunaraz[4] is attractive because it is identical to the name of the ancient Celtic god Taranus (by metathesis–switch of sounds–of an earlier *Tonaros, attested in the dative tanaro and the Gaulish river name Tanarus), and further related to the Latin epithet Tonans (attached to Jupiter), via the common Proto-Indo-European root for 'thunder' *(s)tenh₂-.[5] According to scholar Peter Jackson, those theonyms may have emerged as the result of the fossilization of an original epithet (or epiclesis, i.e. invocational name) of the Proto-Indo-European thunder-god *Perkwunos, since the Vedic weather-god Parjanya is also called stanayitnú- ('Thunderer').[6] The potentially perfect match between the thunder-gods *Tonaros and *Þunaraz, which both go back to a common form *ton(a)ros ~ *tṇros, is notable in the context of early Celtic–Germanic linguistic contacts, especially when added to other inherited terms with thunder attributes, such as *Meldunjaz–*meldo- (from *meldh- 'lightning, hammer', i.e. *Perkwunos' weapon) and *Fergunja–*Fercunyā (from *perkwun-iyā 'wooded mountains', i.e. *Perkwunos' realm).[7]

The English weekday name Thursday comes from Old English Þunresdæg, meaning 'day of Þunor', with influence from Old Norse Þórsdagr. The name is cognate with Old High German Donarestag. All of these terms derive from a Late Proto-Germanic weekday name along the lines of *Þunaresdagaz ('Day of *Þun(a)raz'), a calque of Latin Iovis dies ('Day of Jove'; cf. modern Italian giovedì, French jeudi, Spanish jueves). By employing a practice known as interpretatio germanica during the Roman period, ancient Germanic peoples adopted the Latin weekly calendar and replaced the names of Roman gods with their own.[8][9]

Beginning in the Viking Age, personal names containing the theonym Þórr are recorded with great frequency, whereas no examples are known prior to this period. Þórr-based names may have flourished during the Viking Age as a defiant response to attempts at Christianization, similar to the widespread Viking Age practice of wearing Thor's hammer pendants.[10]

Historical attestations[edit]

Roman era[edit]

The earliest records of the Germanic peoples were recorded by the Romans, and in these works Thor is frequently referred to – via a process known as interpretatio romana (where characteristics perceived to be similar by Romans result in identification of a non-Roman god as a Roman deity) – as either the Roman god Jupiter (also known as Jove) or the Greco-Roman god Hercules.

The first clear example of this occurs in the Roman historian Tacitus's late first-century work Germania, where, writing about the religion of the Suebi (a confederation of Germanic peoples), he comments that "among the gods Mercury is the one they principally worship. They regard it as a religious duty to offer to him, on fixed days, human as well as other sacrificial victims. Hercules and Mars they appease by animal offerings of the permitted kind" and adds that a portion of the Suebi also venerate "Isis".[12] In this instance, Tacitus refers to the god Odin as "Mercury", Thor as "Hercules", and the god Týr as "Mars", and the identity of the Isis of the Suebi has been debated. In Thor's case, the identification with the god Hercules is likely at least in part due to similarities between Thor's hammer and Hercules' club.[13] In his Annals, Tacitus again refers to the veneration of "Hercules" by the Germanic peoples; he records a wood beyond the river Weser (in what is now northwestern Germany) as dedicated to him.[14] A deity known as Hercules Magusanus was venerated in Germania Inferior; due to the Roman identification of Thor with Hercules, Rudolf Simek has suggested that Magusanus was originally an epithet attached to the Proto-Germanic deity *Þunraz.[15]

Post-Roman era[edit]

The first recorded instance of the name of the god appears upon the Nordendorf fibulae, a piece of jewelry created during the Migration Period and found in Bavaria. The item bears an Elder Futhark inscribed with the name Þonar (i.e. Donar), the southern Germanic form of Thor's name.[16]

Around the second half of the 8th century, Old English texts mention Thunor (Þunor), which likely refers to a Saxon version of the god. In relation, Thunor is sometimes used in Old English texts to gloss Jupiter, the god may be referenced in the poem Solomon and Saturn, where the thunder strikes the devil with a "fiery axe", and the Old English expression þunorrād ("thunder ride") may refer to the god's thunderous, goat-led chariot.[17][18]

A 9th-century AD codex from Mainz, Germany, known as the Old Saxon Baptismal Vow, records the name of three Old Saxon gods, UUôden (Old Saxon "Wodan")[clarification needed], Saxnôte, and Thunaer, by way of their renunciation as demons in a formula to be repeated by Germanic pagans formally converting to Christianity.[19]

According to a near-contemporary account, the Christian missionary Saint Boniface felled an oak tree dedicated to "Jove" in the 8th century, the Donar's Oak in the region of Hesse, Germany.[20]

The Kentish royal legend, probably 11th-century, contains the story of a villainous reeve of Ecgberht of Kent called Thunor, who is swallowed up by the earth at a place from then on known as þunores hlæwe (Old English 'Thunor's mound'). Gabriel Turville-Petre saw this as an invented origin for the placename demonstrating loss of memory that Thunor had been a god's name.[21]

Viking age[edit]

In the 11th century, chronicler Adam of Bremen records in his Gesta Hammaburgensis Ecclesiae Pontificum that a statue of Thor, who Adam describes as "mightiest", sits in the Temple at Uppsala in the center of a triple throne (flanked by Woden and "Fricco") located in Gamla Uppsala, Sweden. Adam details that "Thor, they reckon, rules the sky; he governs thunder and lightning, winds and storms, fine weather and fertility" and that "Thor, with his mace, looks like Jupiter". Adam details that the people of Uppsala had appointed priests to each of the gods, and that the priests were to offer up sacrifices. In Thor's case, he continues, these sacrifices were done when plague or famine threatened.[22] Earlier in the same work, Adam relays that in 1030 an English preacher, Wulfred, was lynched by assembled Germanic pagans for "profaning" a representation of Thor.[23]

Two objects with runic inscriptions invoking Thor date from the 11th century, one from England and one from Sweden. The first, the Canterbury Charm from Canterbury, England, calls upon Thor to heal a wound by banishing a thurs.[24] The second, the Kvinneby amulet, invokes protection by both Thor and his hammer.[25]

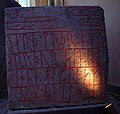

On four (or possibly five) runestones, an invocation to Thor appears that reads "May Thor hallow (these runes/this monument)!" The invocation appears thrice in Denmark (DR 110, DR 209, and DR 220), and a single time in Västergötland (VG 150), Sweden. A fifth appearance may possibly occur on a runestone found in Södermanland, Sweden (Sö 140), but the reading is contested.[26]

Pictorial representations of Thor's hammer appear on a total of five runestones found in Denmark (DR 26 and DR 120) and in the Swedish counties of Västergötland (VG 113) and Södermanland (Sö 86 and Sö 111).[26] It is also seen on runestone DR 48.[citation needed] The design is believed to be a heathen response to Christian runestones, which often have a cross at the centre. One of the stones, Sö 86, shows a face or mask above the hammer. Anders Hultgård has argued that this is the face of Thor.[27] At least three stones depict Thor fishing for the serpent Jörmungandr: the Hørdum stone in Thy, Denmark, the Altuna Runestone in Altuna, Sweden and the Gosforth Cross in Gosforth, England. Sune Lindqvist argued in the 1930s that the image stone Ardre VIII on Gotland depicts two scenes from the story: Thor ripping the head of Hymir's ox and Thor and Hymir in the boat,[28] but this has been disputed.[29]

Image gallery[edit]

-

The Sønder Kirkeby Runestone (DR 220), a runestone from Denmark bearing the "May Thor hallow these runes!" inscription

-

A runestone from Södermanland, Sweden bearing a depiction of Thor's hammer

-

The Altuna stone from Sweden, one of four stones depicting Thor's fishing trip

-

Closeup of Thor with Mjölnir depicted on the Altuna stone.

-

The Gosforth depiction, one of four stones depicting Thor's fishing trip

-

Thor and Jörmungandr by Lorenz Frølich

Post-Viking age[edit]

In the 12th century, more than a century after Norway was "officially" Christianized, Thor was still being invoked by the population, as evidenced by a stick bearing a runic message found among the Bryggen inscriptions in Bergen, Norway. On the stick, both Thor and Odin are called upon for help; Thor is asked to "receive" the reader, and Odin to "own" them.[30]

Poetic Edda[edit]

In the Poetic Edda, compiled during the 13th century from traditional source material reaching into the pagan period, Thor appears (or is mentioned) in the poems Völuspá, Grímnismál, Skírnismál, Hárbarðsljóð, Hymiskviða, Lokasenna, Þrymskviða, Alvíssmál, and Hyndluljóð.[31]