Goldorak theme by TOUGY

Download: Goldorak.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

Redirect to:

The #1 spot for Playstation themes!

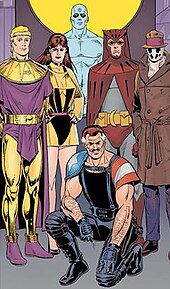

Justice League of America theme by Skyhawke

Download: JLA.p3t

(6 backgrounds)

Redirect to:

This page is a redirect. The following categories are used to track and monitor this redirect:

|

Prototype theme by Gary

Download: Prototype.p3t

(1 background)

A prototype is an early sample, model, or release of a product built to test a concept or process.[1] It is a term used in a variety of contexts, including semantics, design, electronics, and software programming. A prototype is generally used to evaluate a new design to enhance precision by system analysts and users.[2][3] Prototyping serves to provide specifications for a real, working system rather than a theoretical one.[4] Physical prototyping has a long history, and paper prototyping and virtual prototyping now extensively complement it. In some design workflow models, creating a prototype (a process sometimes called materialization) is the step between the formalization and the evaluation of an idea.[5]

A prototype can also mean a typical example of something such as in the use of the derivation 'prototypical'.[6] This is a useful term in identifying objects, behaviours and concepts which are considered the accepted norm and is analogous with terms such as stereotypes and archetypes.

The word prototype derives from the Greek πρωτότυπον prototypon, "primitive form", neutral of πρωτότυπος prototypos, "original, primitive", from πρῶτος protos, "first" and τύπος typos, "impression" (originally in the sense of a mark left by a blow, then by a stamp struck by a die (note "typewriter"); by implication a scar or mark; by analogy a shape i.e. a statue, (figuratively) style, or resemblance; a model for imitation or illustrative example—note "typical").[1][7][8]

Prototypes explore different aspects of an intended design:[9]

In general, the creation of prototypes will differ from creation of the final product in some fundamental ways:

Engineers and prototype specialists attempt to minimize the impact of these differences on the intended role for the prototype. For example, if a visual prototype is not able to use the same materials as the final product, they will attempt to substitute materials with properties that closely simulate the intended final materials.

Engineers and prototyping specialists seek to understand the limitations of prototypes to exactly simulate the characteristics of their intended design.

It is important to recognize that by their very nature, prototypes represent some compromise from the final production design. This is due to not just the skill and choices of the designer(s), but the inevitable inherent limitations of a prototype due to the "map-territory relation". Just as a map is a reduced abstraction representing far more detailed actual territory, or "the menu represents the meal" but cannot capture all the detail of the actual delivered food: a prototype is a necessarily inexact and limited approximation of a "real" final product.

Further, prototypers make both deliberate and unintended choices and tradeoffs for reasons ranging from cost/time savings to what they consider "important" vs. "trivial" aspects to focus design attention and execution on. Due to differences in materials, processes and design fidelity, it is possible that a prototype may fail to perform acceptably although the production design may have been sound. Conversely, and somewhat counter-intuitively: prototypes may actually perform acceptably but the production design and outcome may prove unsuccessful, as prototyping materials and processes may actually outperform their production counterparts.

In general, it can be expected that individual prototype costs will be substantially greater than the final production costs due to inefficiencies in materials and processes. Prototypes are also used to revise the design for the purposes of reducing costs through optimization and refinement.[17]

It is possible to use prototype testing to reduce the risk that a design may not perform as intended, however prototypes generally cannot eliminate all risk. There are pragmatic and practical limitations to the ability of a prototype to match the intended final performance of the product and some allowances and engineering judgement are often required before moving forward with a production design.

Building the full design is often expensive and can be time-consuming, especially when repeated several times—building the full design, figuring out what the problems are and how to solve them, then building another full design. As an alternative, rapid prototyping or rapid application development techniques are used for the initial prototypes, which implement part, but not all, of the complete design. This allows designers and manufacturers to rapidly and inexpensively test the parts of the design that are most likely to have problems, solve those problems, and then build the full design.

This counter-intuitive idea—that the quickest way to build something is, first to build something else—is shared by scaffolding and Thomson's telescope rule.

In technology research, a technology demonstrator is a prototype serving as proof-of-concept and demonstration model for a new technology or future product, proving its viability and illustrating conceivable applications.

In large development projects, a testbed is a platform and prototype development environment for rigorous experimentation and testing of new technologies, components, scientific theories and computational tools.[18]

With recent advances in computer modeling it is becoming practical to eliminate the creation of a physical prototype (except possibly at greatly reduced scales for promotional purposes), instead modeling all aspects of the final product as a computer model. An example of such a development can be seen in Boeing 787 Dreamliner, in which the first full sized physical realization is made on the series production line. Computer modeling is now being extensively used in automotive design, both for form (in the styling and aerodynamics of the vehicle) and in function—especially for improving vehicle crashworthiness and in weight reduction to improve mileage.

The most common use of the word prototype is a functional, although experimental, version of a non-military machine (e.g., automobiles, domestic appliances, consumer electronics) whose designers would like to have built by mass production means, as opposed to a mockup, which is an inert representation of a machine's appearance, often made of some non-durable substance.

An electronics designer often builds the first prototype from breadboard or stripboard or perfboard, typically using "DIP" packages.

However, more and more often the first functional prototype is built on a "prototype PCB" almost identical to the production PCB, as PCB manufacturing prices fall and as many components are not available in DIP packages, but only available in SMT packages optimized for placing on a PCB.

Builders of military machines and aviation prefer the terms "experimental" and "service test".[19]

In electronics, prototyping means building an actual circuit to a theoretical design to verify that it works, and to provide a physical platform for debugging it if it does not. The prototype is often constructed using techniques such as wire wrapping or using a breadboard, stripboard or perfboard, with the result being a circuit that is electrically identical to the design but not physically identical to the final product.[20]

Open-source tools like Fritzing exist to document electronic prototypes (especially the breadboard-based ones) and move toward physical production. Prototyping platforms such as Arduino also simplify the task of programming and interacting with a microcontroller.[21] The developer can choose to deploy their invention as-is using the prototyping platform, or replace it with only the microcontroller chip and the circuitry that is relevant to their product.

A technician can quickly build a prototype (and make additions and modifications) using these techniques, but for volume production it is much faster and usually cheaper to mass-produce custom printed circuit boards than to produce these other kinds of prototype boards. The proliferation of quick-turn PCB fabrication and assembly companies has enabled the concepts of rapid prototyping to be applied to electronic circuit design. It is now possible, even with the smallest passive components and largest fine-pitch packages, to have boards fabricated, assembled, and even tested in a matter of days.Prototype software is often referred to as alpha grade, meaning it is the first version to run. Often only a few functions are implemented, the primary focus of the alpha is to have a functional base code on to which features may be added. Once alpha grade software has most of the required features integrated into it, it becomes beta software for testing of the entire software and to adjust the program to respond correctly during situations unforeseen during development.[22]

Often the end users may not be able to provide a complete set of application objectives, detailed input, processing, or output requirements in the initial stage. After the user evaluation, another prototype will be built based on feedback from users, and again the cycle returns to customer evaluation. The cycle starts by listening to the user, followed by building or revising a mock-up, and letting the user test the mock-up, then back. There is now a new generation of tools called Application Simulation Software which help quickly simulate application before their development.[23]

Extreme programming uses iterative design to gradually add one feature at a time to the initial prototype.[24]

In many programming languages, a function prototype is the declaration of a subroutine or function (and should not be confused with software prototyping). This term is rather C/C++-specific; other terms for this notion are signature, type and interface. In prototype-based programming (a form of object-oriented programming), new objects are produced by cloning existing objects, which are called prototypes.[25]

The term may also refer to the Prototype Javascript Framework.

Additionally, the term may refer to the prototype design pattern.

Continuous learning approaches within organizations or businesses may also use the concept of business or process prototypes through software models.

The concept of prototypicality is used to describe how much a website deviates from the expected norm, and leads to a lowering of user preference for that site's design.[26]

A data prototype is a form of functional or working prototype.[27] The justification for its creation is usually a data migration, data integration or application implementation project and the raw materials used as input are an instance of all the relevant data which exists at the start of the project.

The objectives of data prototyping are to produce:

To achieve this, a data architect uses a graphical interface to interactively develop and execute transformation and cleansing rules using raw data. The resultant data is then evaluated and the rules refined. Beyond the obvious visual checking of the data on-screen by the data architect, the usual evaluation and validation approaches are to use Data profiling software[28] and then to insert the resultant data into a test version of the target application and trial its use.

When developing software or digital tools that humans interact with, a prototype is an artifact that is used to ask and answer a design question. Prototypes provide the means for examining design problems and evaluating solutions.[29]

HCI practitioners can employ several different types of prototypes:

In the field of scale modeling (which includes model railroading, vehicle modeling, airplane modeling, military modeling, etc.), a prototype is the real-world basis or source for a scale model—such as the real EMD GP38-2 locomotive—which is the prototype of Athearn's (among other manufacturers) locomotive model. Technically, any non-living object can serve as a prototype for a model, including structures, equipment, and appliances, and so on, but generally prototypes have come to mean full-size real-world vehicles including automobiles (the prototype 1957 Chevy has spawned many models), military equipment (such as M4 Shermans, a favorite among US Military modelers), railroad equipment, motor trucks, motorcycles, and space-ships (real-world such as Apollo/Saturn Vs, or the ISS). As of 2014, basic rapid prototype machines (such as 3D printers) cost about $2,000, but larger and more precise machines can cost as much as $500,000.[33]

In architecture, prototyping refers to either architectural model making (as form of scale modelling) or as part of aesthetic or material experimentation, such as the Forty Wall House open source material prototyping centre in Australia.[34][35]

Architects prototype to test ideas structurally, aesthetically and technically. Whether the prototype works or not is not the primary focus: architectural prototyping is the revelatory process through which the architect gains insight.[36]

In the science and practice of metrology, a prototype is a human-made object that is used as the standard of measurement of some physical quantity to base all measurement of that physical quantity against. Sometimes this standard object is called an artifact. In the International System of Units (SI), there remains no prototype standard since May 20, 2019. Before that date, the last prototype used was the international prototype of the kilogram, a solid platinum-iridium cylinder kept at the Bureau International des Poids et Mesures (International Bureau of Weights and Measures) in Sèvres France (a suburb of Paris) that by definition was the mass of exactly one kilogram. Copies of this prototype are fashioned and issued to many nations to represent the national standard of the kilogram and are periodically compared to the Paris prototype. Now the kilogram is redefined in such a way that the Planck constant h is prescribed a value of exactly 6.62607015×10−34 joule-second (J⋅s)

Until 1960, the meter was defined by a platinum-iridium prototype bar with two marks on it (that were, by definition, spaced apart by one meter), the international prototype of the metre, and in 1983 the meter was redefined to be the distance in free space covered by light in 1/299,792,458 of a second (thus defining the speed of light to be 299,792,458 meters per second).

In many sciences, from pathology to taxonomy, prototype refers to a disease, species, etc. which sets a good example for the whole category. In biology, prototype is the ancestral or primitive form of a species or other group; an archetype.[37] For example, the Senegal bichir is regarded as the prototypes of its genus, Polypterus.

Death Note theme by Maniac21

Download: DeathNote_2.p3t

(7 backgrounds)

| Death Note | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Genre | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manga | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Written by | Tsugumi Ohba | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Illustrated by | Takeshi Obata | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Published by | Shueisha | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| English publisher | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Imprint | Jump Comics | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magazine | Weekly Shōnen Jump | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demographic | Shōnen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Original run | December 1, 2003 – May 15, 2006 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Volumes | 12 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Death Note (stylized in all caps) is a Japanese manga series written by Tsugumi Ohba and illustrated by Takeshi Obata. It was serialized in Shueisha's shōnen manga magazine Weekly Shōnen Jump from December 2003 to May 2006, with its chapters collected in 12 tankōbon volumes. The story follows Light Yagami, a genius high school student who discovers a mysterious notebook: the "Death Note", which belonged to the shinigami Ryuk, and grants the user the supernatural ability to kill anyone whose name is written in its pages. The series centers around Light's subsequent attempts to use the Death Note to carry out a worldwide massacre of individuals whom he deems immoral and to create a crime-free society, using the alias of a god-like vigilante named "Kira", and the subsequent efforts of an elite Japanese police task force, led by enigmatic detective L, to apprehend him.

A 37-episode anime television series adaptation, produced by Madhouse and directed by Tetsurō Araki, was broadcast on Nippon Television from October 2006 to June 2007. A light novel based on the series, written by Nisio Isin, was also released in 2006. Additionally, various video games have been published by Konami for the Nintendo DS. The series was adapted into three live-action films released in Japan in June, November 2006, and February 2008, and a television drama in 2015. A miniseries titled Death Note: New Generation and a fourth film were released in 2016. An American film adaptation was released exclusively on Netflix in August 2017, and a series is reportedly in the works.

Death Note media, except for video games and soundtracks, is licensed and released in North America by Viz Media. The episodes from the anime first appeared in North America as downloadable from IGN before Viz Media licensed it. The series was aired on YTV's Bionix programming block in Canada and on Adult Swim in the United States with a DVD release following. The live-action films briefly played in certain North American theaters, in 2008, before receiving home video releases. By April 2015, the Death Note manga had over 30 million copies in circulation, making it one of the best-selling manga series.

In Tokyo, a disaffected high school student named Light Yagami finds the "Death Note", a mysterious black notebook with rules that can end anyone's life in seconds as long as the writer knows both the target's true name and face. Light uses the notebook to kill high-profile criminals and is visited by Ryuk, a "shinigami" and the Death Note's previous owner. Ryuk, invisible to anyone who has not touched the notebook, reveals that he dropped the notebook into the human world out of boredom and is amused by Light's actions.[5]

Global media suggest that a single mastermind is responsible for the mysterious murders and name them "Kira" (キラ, the Japanese transliteration of the word "killer"). Interpol requests the assistance of the enigmatic detective L to assist in their investigation. L tricks Light into revealing that he is in the Kanto region of Japan by manipulating him to kill a decoy. Light vows to kill L, whom he views as obstructing his plans. L deduces that Kira has inside knowledge of the Japanese police investigation, led by Light's father, Soichiro Yagami. L assigns a team of FBI agents to monitor the families of those connected with the investigation and designates Light as the prime suspect. Light graduates from high school to college. L recruits Light into the Kira Task Force.

Actress-model Misa Amane obtains a second Death Note from a shinigami named Rem and makes a deal for shinigami eyes, which reveal the names of anyone whose face she sees, at the cost of half her remaining lifespan. Seeking to have Light become her boyfriend, Misa uncovers Light's identity as the original Kira. Light uses her love for him to his advantage, intending to use Misa's shinigami eyes to discern L's true name. L deduces that Misa is likely the second Kira and detains her. Rem threatens to kill Light if he does not find a way to save Misa. Light arranges a scheme in which he and Misa temporarily lose their memories of the Death Note, and has Rem pass the Death Note to Kyosuke Higuchi of the Yotsuba Group.

With memories of the Death Note erased, Light joins the investigation and, together with L, deduces Higuchi's identity and arrests him. Light regains his memories and uses the Death Note to kill Higuchi, regaining possession of the book. After restoring Misa's memories, Light instructs her to begin killing as Kira, causing L to cast suspicion on Misa. Rem realizes Light's plan to have Misa sacrifice herself to kill L. After Rem kills L, she disintegrates and Light obtains her Death Note. The task force agrees to have Light operate as the new L. The investigation stalls but crime rates continue to drop.

Four years later, cults worshipping Kira have risen. L's potential successors are introduced: Near and Mello. Mello joins the mafia whilst Near joins forces with the US government. Mello kidnaps Director Takimura, who is killed by Light. Mello kidnaps Light's sister and exchanges her for the Death Note, using it to kill almost all of Near's team. A Shinigami named Sidoh goes to Earth to reclaim his notebook and ends up meeting and helping Mello. Light uses the notebook to find Mello's hideout, but Soichiro is killed in the mission. Mello and Near exchange information and Mello kidnaps Mogi and gives him to Near. Kira's supporters attack Near's group, but they escape. Shuichi Aizawa, one of the task force members, becomes suspicious of Light and meets with Near. As suspicion falls again on Misa, Light passes Misa's Death Note to Teru Mikami, a fervent Kira supporter, and appoints newscaster Kiyomi Takada as Kira's public spokesperson. Near has Mikami followed whilst Aizawa's suspicions are confirmed. Realizing that Takada is connected to Kira, Mello kidnaps her. Takada kills Mello but is killed by Light. Near arranges a meeting between Light and the current Kira Task Force members. Light tries to have Mikami kill Near as well as all the task force members, but Mikami's Death Note fails to work, having been replaced with a decoy. Near proves Light is Kira discovering Mikami had not written down Light's name. Light is wounded in a scuffle and begs Ryuk to write the names of everyone present. Ryuk instead writes down Light's name in his Death Note, as he had promised to do the day they met, and Light dies.

One year later, the world has returned to normal and the Kira Taskforce Members are conflicted over whether they made the right decision. Meanwhile, cults continue to worship Kira.

Three years later, Near, now functioning as the new L, receives word that a new Kira has appeared. Hearing that the new Kira is randomly killing people, Near concludes that the new Kira is an attention-seeker and denounces the new Kira as "boring" and not worth catching. A shinigami named Midora approaches Ryuk and gives him an apple from the human realm, in a bet to see if a random human could become the new Kira, but Midora loses the bet when the human writes his own name in the Death Note after hearing Near's announcement. Ryuk tells Midora that no human would ever surpass Light as the new Kira.

Another ten years later, Ryuk returns to Earth and gives the Death Note to Minoru Tanaka, the top-scoring student in Japan, hoping that he will follow in Light Yagami's footsteps. On explaining the rules to Minoru, Ryuk is surprised when he returns the notebook and tells him to return it and his memory of their encounter to him in two years' time. Two years later, on receiving the notebook back from Ryuk, Minoru reveals he has no plans to use it himself but rather he plans to auction it off to the governments of the world, with Ryuk's help sending his offer out as "a-Kira", having waited two years until he was old enough to have a bank account to allow his plan to work. Elsewhere, Near (as L) is revealed to be developing technology meant to track and eventually find a method of destroying Shinigami, although it is not yet advanced enough to be useful. After selling the Death Note to U.S. President Donald Trump for a sum that would ensure every Japanese citizen under the age of 60 would be financially set for life, Minoru relinquishes his ownership and memory of his plan to Ryuk, assuring his own anonymity, while Trump is left unable to use the Death Note after the King of Death creates a new rule disallowing the Death Note to be sold, and he secretly returns it to Ryuk. Minoru collapses to the ground in the bank after withdrawing his savings. It is revealed that Ryuk wrote his name in the Death Note next to Light's. He longs for a human who will use the notebook for a longer period of time.

The Death Note concept derived from a rather general concept involving Shinigami and "specific rules".[6] Author Tsugumi Ohba wanted to create a suspense series because the genre had some suspense series available to the public. After the publication of the pilot chapter, the series was not expected to receive approval as a serialized comic. Learning that Death Note had received approval and that Takeshi Obata would create the artwork, Ohba said, they "couldn't even believe it".[7] Due to positive reactions, Death Note became a serialized manga series.[8]

"Thumbnails" incorporating dialogue, panel layout and basic drawings were created, reviewed by an editor and sent to Takeshi Obata, the illustrator, with the script finalized and the panel layout "mostly done". Obata then determined the expressions and "camera angles" and created the final artwork. Ohba concentrated on the tempo and the amount of dialogue, making the text as concise as possible. Ohba commented that "reading too much exposition" would be tiring and would negatively affect the atmosphere and "air of suspense". The illustrator had significant artistic licence to interpret basic descriptions, such as "abandoned building",[9] as well as the design of the Death Notes themselves.

When Ohba was deciding on the plot, they visualized the panels while relaxing on their bed, drinking tea, or walking around their house. Often the original draft was too long and needed to be refined to finalize the desired "tempo" and "flow". The writer remarked on their preference for reading the previous "two or four" chapters carefully to ensure consistency in the story.[6]

The typical weekly production schedule consisted of five days of creating and thinking and one day using a pencil to insert dialogue into rough drafts; after this point, the writer faxed any initial drafts to the editor. The illustrator's weekly production schedule involved one day with the thumbnails, layout, and pencils and one day with additional penciling and inking. Obata's assistants usually worked for four days and Obata spent one day to finish the artwork. Obata said that when he took a few extra days to color the pages, this "messed with the schedule". In contrast, the writer took three or four days to create a chapter on some occasions, while on others they took a month. Obata said that his schedule remained consistent except when he had to create color pages.[10]

Ohba and Obata rarely met in person during the creation of the serialized manga; instead, the two met with the editor. The first time they met in person was at an editorial party in January 2004. Obata said that, despite the intrigue, he did not ask his editor about Ohba's plot developments as he anticipated the new thumbnails every week.[7] The two did not discuss the final chapters with one another and continued talking only with the editor. Ohba said that when they asked the editor if Obata had "said anything" about the story and plot, the editor responded: "No, nothing".[9]

Ohba claims that the series ended more or less in the manner that they intended for it to end; they considered the idea of L defeating Light Yagami with Light dying but instead chose to use the "Yellow Box Warehouse" ending. According to Ohba, the details had been set "from the beginning".[8] The writer wanted an ongoing plot line instead of an episodic series because Death Note was serialized and its focus was intended to be on a cast with a series of events triggered by the Death Note.[11] 13: How to Read states that the humorous aspects of Death Note originated from Ohba's "enjoyment of humorous stories".[12]

When Ohba was asked, during an interview, whether the series was meant to be about enjoying the plot twists and psychological warfare, Ohba responded by saying that this concept was the reason why they were "very happy" to place the story in Weekly Shōnen Jump.[10]

The core plot device of the story is the "Death Note" itself, a black notebook with instructions (known as "Rules of the Death Note") written on the inside. When used correctly, it allows anyone to commit a murder, knowing only the victim's name and face. According to the director of the live-action films, Shusuke Kaneko, "The idea of spirits living in words is an ancient Japanese concept.... In a way, it's a very Japanese story".[13]

Artist Takeshi Obata originally thought of the books as "Something you would automatically think was a Death Note". Deciding that this design would be cumbersome, he instead opted for a more accessible college notebook. Death Notes were originally conceived as changing based on time and location, resembling scrolls in ancient Japan, or the Old Testament in medieval Europe. However, this idea was never used.[14]

Writer Tsugumi Ohba had no particular themes in mind for Death Note. When pushed, he suggested: "Humans will all eventually die, so let's give it our all while we're alive".[15] In a 2012 paper, author Jolyon Baraka Thomas characterised Death Note as a psychological thriller released in the wake of the 1995 Tokyo subway sarin attack, saying that it examines the human tendency to express itself through "horrific" cults.[16]

The Death Note process began when Ohba brought thumbnails for two concept ideas to Shueisha; Ohba said that the Death Note pilot, one of the concepts, was "received well" by editors and attained positive reactions from readers.[8] Ohba described keeping the story of the pilot to one chapter as "very difficult", declaring that it took over a month to begin writing the chapter. He added that the story had to revive the killed characters with the Death Eraser and that he "didn't really care" for that plot device.[17]

Obata said that he wanted to draw the story after he heard of a "horror story featuring shinigami".[7] According to Obata, when he first received the rough draft created by Ohba, he "didn't really get it" at first, and he wanted to work on the project due to the presence of shinigami and because the work "was dark".[17] He also said he wondered about the progression of the plot as he read the thumbnails, and if Jump readers would enjoy reading the comic. Obata said that while there is little action and the main character "doesn't really drive the plot", he enjoyed the atmosphere of the story. He stated that he drew the pilot chapter so that it would appeal to himself.[17]

Ohba brought the rough draft of the pilot chapter to the editorial department. Obata came into the picture at a later point to create the artwork. They did not meet in person while creating the pilot chapter. Ohba said that the editor told him he did not need to meet with Obata to discuss the pilot; Ohba said "I think it worked out all right".[7]

Tetsurō Araki, the director, said that he wished to convey aspects that "made the series interesting" instead of simply "focusing on morals or the concept of justice". Toshiki Inoue, the series organizer, agreed with Araki and added that, in anime adaptations, there is a lot of importance in highlighting the aspects that are "interesting in the original". He concluded that Light's presence was "the most compelling" aspect; therefore the adaptation chronicles Light's "thoughts and actions as much as possible". Inoue noted that to best incorporate the manga's plot into the anime, he "tweak[ed] the chronology a bit" and incorporated flashbacks that appear after the openings of the episodes; he said this revealed the desired tensions. Araki said that, because in an anime the viewer cannot "turn back pages" in the manner that a manga reader can, the anime staff ensured that the show clarified details. Inoue added that the staff did not want to get involved with every single detail, so the staff selected elements to emphasize. Due to the complexity of the original manga, he described the process as "definitely delicate and a great challenge". Inoue admitted that he placed more instructions and notes in the script than usual. Araki added that because of the importance of otherwise trivial details, this commentary became crucial to the development of the series.[18]

Araki said that when he discovered the Death Note anime project, he "literally begged" to join the production team; when he joined he insisted that Inoue should write the scripts. Inoue added that, because he enjoyed reading the manga, he wished to use his effort.[18]

Death Note, written by Tsugumi Ohba and illustrated by Takeshi Obata, was serialized in Shueisha's shōnen manga magazine Weekly Shōnen Jump from December 1, 2003,[19][20] to May 15, 2006.[b][20] The series' 108 chapters were collected into twelve tankōbon volumes by Shueisha, released from April 2, 2004,[23] to July 4, 2006.[24] A one-shot chapter, titled "C-Kira" (Cキラ編, C-Kira-hen) ("Death Note: Special One-Shot"), was published in Weekly Shōnen Jump on February 9, 2008. Set two years after the manga's epilogue, it sees the introduction of a new Kira and the reactions of the main characters in response to the copycat's appearance.[25] Several Death Note yonkoma (four-panel comics) appeared in Akamaru Jump. The yonkoma was written to be humorous. The Akamaru Jump issues that printed the comics include 2004 Spring, 2004 Summer, 2005 Winter, and 2005 Spring. In addition Weekly Shōnen Jump Gag Special 2005 included some Death Note yonkoma in a Jump Heroes Super 4-Panel Competition.[17] Shueisha re-released the series in seven bunkoban volumes from March 18 to August 19, 2014.[26][27] On October 4, 2016, all 12 original manga volumes and the February 2008 one-shot were released in a single All-in-One Edition, consisting of 2,400 pages in a single book.[28][29]

In April 2005, Viz Media announced that they had licensed the series for English release in North America.[30] The twelve volumes were released from October 10, 2005, to July 3, 2007.[31][32] The manga was re-released in a six-volume omnibus edition, dubbed "Black Edition".[33][34] The volumes were released from December 28, 2010, to November 1, 2011.[35][36] The All-in-One Edition was released in English on September 6, 2017, resulting in the February 2008 one-shot being released in English for the first time.[37]

In addition, a guidebook for the manga was also released on October 13, 2006. It was named Death Note 13: How to Read and contained data relating to the series, including character profiles of almost every character that is named, creator interviews, behind the scenes info for the series and the pilot chapter that preceded Death Note. It also reprinted all of the yonkoma serialized in Akamaru Jump and the Weekly Shōnen Jump Gag Special 2005.

Watchmen theme by Proinsias Download: Watchmen.p3t

Watchmen is a comic book limited series by the British creative team of writer Alan Moore, artist Dave Gibbons and colorist John Higgins. It was published monthly by DC Comics in 1986 and 1987 before being collected in a single-volume edition in 1987. Watchmen originated from a story proposal Moore submitted to DC featuring superhero characters that the company had acquired from Charlton Comics. As Moore's proposed story would have left many of the characters unusable for future stories, managing editor Dick Giordano convinced Moore to create original characters instead.

Moore used the story as a means of reflecting contemporary anxieties, of deconstructing and satirizing the superhero concept and of making political commentary. Watchmen depicts an alternate history in which superheroes emerged in the 1940s and 1960s and their presence changed history so that the United States won the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal was never exposed. In 1985 the country is edging toward World War III with the Soviet Union, freelance costumed vigilantes have been outlawed and most former superheroes are in retirement or working for the government. The story focuses on the protagonists' personal development and moral struggles as an investigation into the murder of a government-sponsored superhero pulls them out of retirement.

Gibbons uses a nine-panel grid layout throughout the series and adds recurring symbols such as a blood-stained smiley face. All but the last issue feature supplemental fictional documents that add to the series' backstory and the narrative is intertwined with that of another story, an in-story pirate comic titled Tales of the Black Freighter, which one of the characters reads. Structured at times as a nonlinear narrative, the story skips through space, time and plot. In the same manner, entire scenes and dialogues have parallels with others through synchronicity, coincidence, and repeated imagery.

A commercial success, Watchmen has received critical acclaim both in the comics and mainstream press. Watchmen was recognized in Time's List of the 100 Best Novels as one of the best English language novels published since 1923. In a retrospective review, the BBC's Nicholas Barber described it as "the moment comic books grew up".[1] Moore opposed this idea, stating, "I tend to think that, no, comics hadn't grown up. There were a few titles that were more adult than people were used to. But the majority of comics titles were pretty much the same as they'd ever been. It wasn't comics growing up. I think it was more comics meeting the emotional age of the audience coming the other way."[2]

After a number of attempts to adapt the series into a feature film, director Zack Snyder's Watchmen was released in 2009. A video game series, Watchmen: The End Is Nigh, was released to coincide with the film's release.

DC Comics published Before Watchmen, a series of nine prequel miniseries, in 2012, and Doomsday Clock, a 12-issue limited series and sequel to the original Watchmen series, from 2017 to 2019 – both without Moore's or Gibbons' involvement. The second series integrated the Watchmen characters within the DC Universe. A standalone sequel, Rorschach by Tom King, began publication in October 2020. A television continuation to the original comic, set 34 years after the comic's timeline, was broadcast on HBO from October to December 2019 with Gibbons' involvement. Moore has expressed his displeasure with adaptations and sequels of Watchmen and asked it not be used for future works.[3]

Watchmen, created by writer Alan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons, first appeared in the 1985 issue of DC Spotlight, the 50th anniversary special. It was eventually published as a 12-issue maxiseries from DC Comics, cover-dated September 1986 to October 1987.[4]

It was subsequently collected in 1987 as a DC Comics trade paperback that has had at least 24 printings as of March 2017;[17] another trade paperback was published by Warner Books, a DC sister company, in 1987.[18] In February 1988, DC published a limited-edition, slipcased hardcover volume, produced by Graphitti Design, that contained 48 pages of bonus material, including the original proposal and concept art.[19][20] In 2005, DC released Absolute Watchmen, an oversized slipcased hardcover edition of the series in DC's Absolute Edition format. Assembled under the supervision of Dave Gibbons, Absolute Watchmen included the Graphitti materials, as well as restored and recolored art by John Higgins.[21] That December DC published a new printing of Watchmen issue #1 at the original 1986 cover price of $1.50 as part of its "Millennium Edition" line.[22]

In 2012, DC published Before Watchmen, a series of nine prequel miniseries, with various creative teams producing the characters' early adventures set before the events of the original series.[23]

In the 2016 one-shot DC Universe: Rebirth Special, numerous symbols and visual references to Watchmen, such as the blood-splattered smiley face, and the dialogue between Doctor Manhattan and Ozymandias in the last issue of Watchmen, are shown.[24] Further Watchmen imagery was added in the DC Universe: Rebirth Special #1 second printing, which featured an update to Gary Frank's cover, better revealing the outstretched hand of Doctor Manhattan in the top right corner.[25][26] Doctor Manhattan later appeared in the 2017 four-part DC miniseries The Button serving as a direct sequel to both DC Universe Rebirth and the 2011 storyline "Flashpoint". Manhattan reappears in the 2017–19 twelve-part sequel series Doomsday Clock.[27]

"I suppose I was just thinking, 'That'd be a good way to start a comic book: have a famous super-hero found dead.' As the mystery unraveled, we would be led deeper and deeper into the real heart of this super-hero's world, and show a reality that was very different to the general public image of the super-hero."

—Alan Moore on the basis for Watchmen[28] In 1983, DC Comics acquired a line of characters from Charlton Comics.[29] During that period, writer Alan Moore contemplated writing a story that featured an unused line of superheroes that he could revamp, as he had done in his Miracleman series in the early 1980s. Moore reasoned that MLJ Comics' Mighty Crusaders might be available for such a project, so he devised a murder mystery plot which would begin with the discovery of the body of the Shield in a harbor. The writer felt it did not matter which set of characters he ultimately used, as long as readers recognized them "so it would have the shock and surprise value when you saw what the reality of these characters was".[28] Moore used this premise and crafted a proposal featuring the Charlton characters titled Who Killed the Peacemaker,[30] and submitted the unsolicited proposal to DC managing editor Dick Giordano.[31] Giordano was receptive to the proposal, but opposed the idea of using the Charlton characters for the story. After the acquisition of Charlton's Action Hero line, DC intended to use their upcoming Crisis on Infinite Earths event to fold them into their mainstream superhero universe. Moore said, "DC realized their expensive characters would end up either dead or dysfunctional." Instead, Giordano persuaded Moore to continue his project but with new characters that simply resembled the Charlton heroes.[32][33][34] Moore had initially believed that original characters would not provide emotional resonance for readers but later changed his mind. He said, "Eventually, I realized that if I wrote the substitute characters well enough, so that they seemed familiar in certain ways, certain aspects of them brought back a kind of generic super-hero resonance or familiarity to the reader, then it might work."[28]

Artist Dave Gibbons, who had collaborated with Moore on previous projects, recalled that he "must have heard on the grapevine that he was doing a treatment for a new miniseries. I rang Alan up, saying I'd like to be involved with what he was doing", and Moore sent him the story outline.[35] Gibbons told Giordano he wanted to draw the series Moore proposed and Moore approved.[36] Gibbons brought colorist John Higgins onto the project because he liked his "unusual" style; Higgins lived near the artist, which allowed the two to "discuss [the art] and have some kind of human contact rather than just sending it across the ocean".[30] Len Wein joined the project as its editor, while Giordano stayed on to oversee it. Both Wein and Giordano stood back and "got out of their way", as Giordano remarked later. "Who copy-edits Alan Moore, for God's sake?"[31]

After receiving the go-ahead to work on the project, Moore and Gibbons spent a day at the latter's house creating characters, crafting details for the story's milieu and discussing influences. The pair were particularly influenced by a Mad parody of Superman named "Superduperman"; Moore said: "We wanted to take Superduperman 180 degrees—dramatic, instead of comedic".[34] Moore and Gibbons conceived of a story that would take "familiar old-fashioned superheroes into a completely new realm";[37] Moore said his intention was to create "a superhero Moby Dick; something that had that sort of weight, that sort of density".[38] Moore came up with the character names and descriptions but left the specifics of how they looked to Gibbons. Gibbons did not sit down and design the characters deliberately, but rather "did it at odd times [...] spend[ing] maybe two or three weeks just doing sketches."[30] Gibbons designed his characters to make them easy to draw; Rorschach was his favorite to draw because "you just have to draw a hat. If you can draw a hat, then you've drawn Rorschach, you just draw kind of a shape for his face and put some black blobs on it and you're done."[39]

Moore began writing the series very early on, hoping to avoid publication delays such as those faced by the DC limited series Camelot 3000.[40] When writing the script for the first issue Moore said he realized "I only had enough plot for six issues. We were contracted for 12!" His solution was to alternate issues that dealt with the overall plot of the series with origin issues for the characters.[41] Moore wrote very detailed scripts for Gibbons to work from. Gibbons recalled that "[t]he script for the first issue of Watchmen was, I think, 101 pages of typescript—single-spaced—with no gaps between the individual panel descriptions or, indeed, even between the pages." Upon receiving the scripts, the artist had to number each page "in case I drop them on the floor, because it would take me two days to put them back in the right order", and used a highlighter pen to single out lettering and shot descriptions; he remarked, "It takes quite a bit of organizing before you can actually put pen to paper."[42] Despite Moore's detailed scripts, his panel descriptions would often end with the note "If that doesn't work for you, do what works best"; Gibbons nevertheless worked to Moore's instructions.[43] In fact, Gibbons only suggested one single change to the script - a compression of Ozymandias' narration while he was preventing a sneak attack by Rorschach - as he felt that the dialogue was too long to fit with the length of the action; Moore agreed and re-wrote the scene.[44] Gibbons had a great deal of autonomy in developing the visual look of Watchmen and frequently inserted background details that Moore admitted he did not notice until later.[38] Moore occasionally contacted fellow comics writer Neil Gaiman for answers to research questions and for quotes to include in issues.[41]

Despite his intentions, Moore admitted in November 1986 that there were likely to be delays, stating that he was, with issue five on the stands, still writing issue nine.[42] Gibbons mentioned that a major factor in the delays was the "piecemeal way" in which he received Moore's scripts. Gibbons said the team's pace slowed around the fourth issue; from that point onward the two undertook their work "just several pages at a time. I'll get three pages of script from Alan and draw it and then toward the end, call him up and say, 'Feed me!' And he'll send another two or three pages or maybe one page or sometimes six pages."[45] As the creators began to hit deadlines, Moore would hire a taxi driver to drive 50 miles and deliver scripts to Gibbons. On later issues the artist even had his wife and son draw panel grids on pages to help save time.[41]

Near the end of the project, Moore realized that the story bore some similarity to "The Architects of Fear", an episode of The Outer Limits television series.[41] The writer and Wein (an editor) argued over changing the ending and when Moore refused to give in, Wein quit the book. Wein explained, "I kept telling him, 'Be more original, Alan, you've got the capability, do something different, not something that's already been done!' And he didn't seem to care enough to do that."[46] Moore acknowledged the Outer Limits episode by referencing it in the series' last issue.[43]

Watchmen is set in an alternate reality that closely mirrors the contemporary world of the 1980s. The primary difference is the presence of superheroes. The point of divergence occurs in the year 1938. Their existence in this version of the United States is shown to have dramatically affected and altered the outcomes of real-world events such as the Vietnam War and the presidency of Richard Nixon.[47] In keeping with the realism of the series, although the costumed crimefighters of Watchmen are commonly called "superheroes", only one, named Doctor Manhattan, possesses any superhuman abilities.[48] The war in Vietnam ends with an American victory in 1971 and Nixon is still president as of October 1985 upon the repeal of term limits and the Watergate scandal not coming to pass. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan occurs approximately six years later than in real life.

When the story begins, the existence of Doctor Manhattan has given the U.S. a strategic advantage over the Soviet Union, which has dramatically increased Cold War tensions. Eventually, by 1977, superheroes grow unpopular among the police and the public, leading them to be outlawed with the passage of the Keene Act. While many of the heroes retired, Doctor Manhattan and another superhero, known as The Comedian, operate as government-sanctioned agents. Another named Rorschach continues to operate outside the law.[49]

In October 1985, New York City detectives investigate the murder of Edward Blake. With the police having no leads, costumed vigilante Rorschach decides to probe further. Rorschach deduces Blake to have been the true identity of "The Comedian", a costumed hero employed by the U.S. government, after finding his costume and signature smiley-face pin badge. Believing that Blake's murder could be part of a larger plot against costumed adventurers, Rorschach seeks out and warns four of his retired comrades: shy inventor Daniel Dreiberg, formerly the second Nite Owl; the superpowered and emotionally detached Jon Osterman, codenamed "Doctor Manhattan"; Doctor Manhattan's lover Laurie Juspeczyk, the second Silk Spectre; and Adrian Veidt, once the hero "Ozymandias", and now a successful businessman.

Dreiberg, Veidt, and Manhattan attend Blake's funeral, where Dreiberg tosses Blake's pin badge in his coffin before he is buried. Manhattan is later accused on national television of being the cause of cancer in friends and former colleagues. When the government takes the accusations seriously, Manhattan exiles himself to Mars. As the United States depends on Manhattan as a strategic military asset, his departure throws humanity into political turmoil, with the Soviets invading Afghanistan to capitalize on the United States' perceived weakness. Rorschach's concerns appear validated when Veidt narrowly survives an assassination attempt. Rorschach himself is framed for murdering a former supervillain named Moloch. While attempting to flee the scene of Moloch's murder, Rorschach is captured by police and unmasked as Walter Kovacs.

Neglected in her relationship with the once-human Manhattan, whose godlike powers have left him emotionally detached from ordinary people, and no longer kept on retainer by the government, Juspeczyk stays with Dreiberg. They begin a romance, don their costumes, and resume vigilante work as they grow closer together. With Dreiberg starting to believe some aspects of Rorschach's conspiracy theory, the pair take it upon themselves to break him out of prison. After looking back on his own personal history, Manhattan places the fate of his involvement with human affairs in Juspeczyk's hands. He teleports her to Mars to make the case for emotional investment. During the course of the argument, Juspeczyk is forced to come to terms with the fact that Blake, who once attempted to rape her mother (the original Silk Spectre), was actually her biological father, having fathered her in a second, consensual relationship. This discovery, reflecting the complexity of human emotions and relationships, reignites Manhattan's interest in humanity.

On Earth, Dreiberg and Rorschach find evidence that Veidt may be behind the conspiracy. Rorschach writes his suspicions about Veidt in his journal, which includes the full details of his investigation, and mails it to New Frontiersman, a local right-wing newspaper. When Rorschach and Dreiberg travel to Antarctica to confront Veidt at his private retreat, Veidt explains that he plans to save humanity from an impending nuclear war by staging a fake alien invasion and killing half the population of New York, forcing the United States and the Soviet Union to unite against a common enemy. He reveals that he murdered Blake after he discovered his plan, arranged for Doctor Manhattan's past associates to contract cancer to force him to leave Earth, staged the attempt on his own life to place himself above suspicion, and framed Rorschach for Moloch's murder to prevent him from discovering the truth. Horrified by Veidt's callous logic, Dreiberg and Rorschach vow to stop him, but Veidt reveals that he already enacted his plan before they arrived.

When Manhattan and Juspeczyk arrive back on Earth, they are confronted by mass destruction and death in New York, with a gigantic squid-like creature, created by Veidt's laboratories, dead in the middle of the city. Manhattan notices his prescient abilities are limited by tachyons emanating from the Antarctic and the pair teleport there. They discover Veidt's involvement and confront him. Veidt shows everyone news broadcasts confirming that the emergence of a new threat has indeed prompted peaceful co-operation between the superpowers; this leads almost all present to agree that concealing the truth is in the best interests of world peace. Rorschach refuses to compromise and leaves, intent on revealing the truth. As he is making his way back, he is confronted by Manhattan who argues that at this point, the truth can only hurt. Rorschach declares that Manhattan will have to kill him to stop him from exposing Veidt, which Manhattan duly does. Manhattan then wanders through the base and finds Veidt, who asks him if he did the right thing in the end. Manhattan cryptically responds that "nothing ever ends" before leaving Earth. Dreiberg and Juspeczyk go into hiding under new identities and continue their romance.

Back in New York, the editor at New Frontiersman asks his assistant to find some filler material from the "crank file", a collection of rejected submissions to the paper, many of which have not yet been reviewed. The series ends with the young man reaching toward the pile of discarded submissions, near the top of which is Rorschach's journal.

With Watchmen, Alan Moore's intention was to create four or five "radically opposing ways" to perceive the world and to give readers of the story the privilege of determining which one was most morally comprehensible. Moore did not believe in the notion of "[cramming] regurgitated morals" down the readers' throats and instead sought to show heroes in an ambivalent light. Moore said, "What we wanted to do was show all of these people, warts and all. Show that even the worst of them had something going for them, and even the best of them had their flaws."[38]

Felicia theme by YASAI Download: Felicia.p3t The name Felicia derives from the Latin adjective felix, meaning "happy, lucky", though in the neuter plural form felicia it literally means "happy things" and often occurred in the phrase tempora felicia, "happy times". The sense of it as a feminine personal name appeared in post-Classical use and is of uncertain origin. It is associated with saints, poets, astronomical objects, plant genera, fictional characters, and animals, especially cats.

Air (Anime) theme by Goofy Download: Air.p3t P3T Unpacker v0.12 This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit! Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip Instructions: Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme. The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract. The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following: Gundam-Meta theme by Anthony Michel Download: Gundam-Meta.p3t P3T Unpacker v0.12 This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit! Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip Instructions: Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme. The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract. The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following: Bleach High Definition theme by TheSTIG_992 Download: BleachHD.p3t P3T Unpacker v0.12 This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit! Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip Instructions: Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme. The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract. The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following: Gundam-01 theme by Anthony Michel Download: Gundam-01.p3t P3T Unpacker v0.12 This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit! Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip Instructions: Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme. The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract. The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following:Watchmen

(13 backgrounds)

Watchmen

Art by Dave GibbonsDate 1986–1987 Publisher DC Comics Creative team Writer Alan Moore Artist Dave Gibbons Colorist John Higgins Editors Original publication Published in Watchmen Issues 12 Date of publication September 1986 – October 1987 Publication history[edit]

No.

Title

Publication date

On-sale date

Ref.

"At Midnight, All the Agents..."

September 1986

May 13, 1986

"Absent Friends"

October 1986

June 10, 1986

"The Judge of All the Earth"

November 1986

July 8, 1986

"Watchmaker"

December 1986

August 12, 1986

"Fearful Symmetry"

January 1987

September 9, 1986

"The Abyss Gazes Also"

February 1987

October 14, 1986

"A Brother to Dragons"

March 1987

November 11, 1986

"Old Ghosts"

April 1987

December 9, 1986

"The Darkness of Mere Being"

May 1987

January 13, 1987

"Two Riders Were Approaching..."

July 1987

March 17, 1987

"Look on My Works, Ye Mighty..."

August 1987

May 19, 1987

"A Stronger Loving World"

October 1987

July 28, 1987

Background and creation[edit]

Synopsis[edit]

Setting[edit]

Plot[edit]

Characters[edit]

Art and composition[edit]

Felicia

(1 background)

Gender Female Origin Word/name Latin Meaning Happiness Other names Short form(s) Licia, Fish, Lica, Elle, Fliss, Felly, Lish, Fia, Ellie, Flea Related names Felix, Felicity, Félicie ![]()

People[edit]

Fictional characters[edit]

Other uses[edit]

Air (Anime)

(9 backgrounds)

Copyright (c) 2007. Anoop Menon

p3textractor filename.p3t [destination path]Replace filename with the name of the p3t file, and replace [destination path] with the name of the folder you want the files to be extracted to. A destination path is not required. By default it will extract to extracted.filename.Gundam-Meta

(1 background)

Copyright (c) 2007. Anoop Menon

p3textractor filename.p3t [destination path]Replace filename with the name of the p3t file, and replace [destination path] with the name of the folder you want the files to be extracted to. A destination path is not required. By default it will extract to extracted.filename.Bleach High Definition

(16 backgrounds)

Copyright (c) 2007. Anoop Menon

p3textractor filename.p3t [destination path]Replace filename with the name of the p3t file, and replace [destination path] with the name of the folder you want the files to be extracted to. A destination path is not required. By default it will extract to extracted.filename.Gundam-01

(1 background)

Copyright (c) 2007. Anoop Menon

p3textractor filename.p3t [destination path]Replace filename with the name of the p3t file, and replace [destination path] with the name of the folder you want the files to be extracted to. A destination path is not required. By default it will extract to extracted.filename.