One Piece theme by BlackOps

Download: OnePiece_2.p3t

(4 backgrounds)

| One Piece | |

| |

| Genre | |

|---|---|

| Manga | |

| Written by | Eiichiro Oda |

| Published by | Shueisha |

| English publisher | |

| Imprint | Jump Comics |

| Magazine | Weekly Shōnen Jump |

| English magazine | |

| Demographic | Shōnen |

| Original run | July 22, 1997 – present |

| Volumes | 108 |

| Anime television series | |

| |

| Media franchise | |

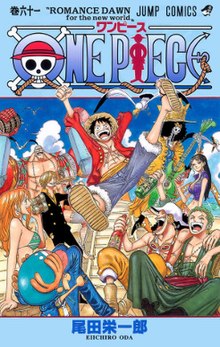

One Piece (stylized in all caps) is a Japanese manga series written and illustrated by Eiichiro Oda. It has been serialized in Shueisha's shōnen manga magazine Weekly Shōnen Jump since July 1997, with its individual chapters compiled in 108 tankōbon volumes as of March 2024[update]. The story follows the adventures of Monkey D. Luffy and his crew, the Straw Hat Pirates, where he explores the Grand Line in search of the mythical treasure known as the "One Piece" in order to become the next King of the Pirates.

The manga spawned a media franchise, having been adapted into a festival film by Production I.G, and an anime series by Toei Animation, which began broadcasting in 1999. Additionally, Toei has developed fourteen animated feature films, one original video animation, and thirteen television specials. Several companies have developed various types of merchandising and media, such as a trading card game and numerous video games. The manga series was licensed for an English language release in North America and the United Kingdom by Viz Media and in Australia by Madman Entertainment. The anime series was licensed by 4Kids Entertainment for an English-language release in North America in 2004 before the license was dropped and subsequently acquired by Funimation in 2007.

One Piece has received praise for its storytelling, world-building, art, characterization, and humor. It has received many awards and is ranked by critics, reviewers, and readers as one of the best manga of all time. By August 2022, it had over 516.6 million copies in circulation in 61 countries and regions worldwide, making it the best-selling manga series in history, and the best-selling comic series printed in book volume. Several volumes of the manga have broken publishing records, including the highest initial print run of any book in Japan. In 2015 and 2022, One Piece set the Guinness World Record for "the most copies published for the same comic book series by a single author". It was the best-selling manga for eleven consecutive years from 2008 to 2018, and is the only manga that had an initial print of volumes of above 3 million continuously for more than 10 years, as well as the only that had achieved more than 1 million copies sold in all of its over 100 published tankōbon volumes. One Piece is the only manga whose volumes have ranked first every year in Oricon's weekly comic chart existence since 2008.

Synopsis[edit]

Setting[edit]

The world of One Piece is populated by humans and other races such as dwarves (more akin to faeries in size), giants, merfolk, fish-men, long-limbed tribes, long-necked people known as the Snakeneck Tribe, and animal people (known as "Minks"). The world is governed by an intercontinental organization known as the World Government, consisting of dozens of member countries. The Navy is the sea military branch of the World Government that protects the known seas from pirates and other criminals. There is also Cipher Pol which is a group of agencies within the World Government that are their secret police. While pirates are major opponents against the Government, the ones who really challenge their rule are the Revolutionary Army who seeks to overthrow them. The central tension of the series pits the World Government and their forces against pirates. The series regularly emphasizes moral ambiguity over the label "pirate", which includes cruel villains, but also any individuals that do not submit to the World Government's authoritarian—and often morally ambiguous—rule. The One Piece world also has supernormal characteristics like Devil Fruits,[Jp 1] which are mysterious fruits that grant whoever eats them transformative powers. Another supernatural power is Haki,[Jp 2] which grants its users enhanced willpower, observation, and fighting abilities, and it is one of the only effective methods of inflicting bodily harm on certain Devil Fruit users.

The world itself consists of two vast oceans divided by a massive mountain range called the Red Line.[Jp 3] Within the oceans is a second global phenomenon known as the Grand Line,[Jp 4] which is a sea that runs perpendicular to the Red Line and is bounded by the Calm Belt,[Jp 5] strips of calm ocean infested with huge ship-eating monsters known as Sea Kings.[Jp 6] These geographical barriers divide the world into four seas: North Blue,[Jp 7] East Blue,[Jp 8] West Blue,[Jp 9] and South Blue.[Jp 10] Passage between the four seas, and the Grand Line, is therefore difficult. Unique and mystical features enable transport between the seas, such as the use of Sea Prism Stone[Jp 11] employed by government ships to mask their presence as they traverse the Calm Belt, or the Reverse Mountain[Jp 12] where water from the four seas flows uphill before merging into a rapidly flowing and dangerous canal that enters the Grand Line. The Grand Line itself is split into two separate halves with the Red Line between being Paradise[Jp 13] and the New World.[Jp 14]

Premise[edit]

The series focuses on Monkey D. Luffy—a young man made of rubber after unintentionally eating a Devil Fruit—who sets off on a journey from the East Blue Sea to find the deceased King of the Pirates Gol D. Roger's ultimate treasure known as the "One Piece", and take over his prior title. In an effort to organize his own crew, the Straw Hat Pirates,[Jp 15] Luffy rescues and befriends a pirate hunter and swordsman named Roronoa Zoro, and they head off in search of the titular treasure. They are joined in their journey by Nami, a money-obsessed thief and navigator; Usopp, a sniper and compulsive liar; and Sanji, an amorous but chivalrous cook. They acquire a ship, the Going Merry[Jp 16]—later replaced by the Thousand Sunny[Jp 17]—and engage in confrontations with notorious pirates. As Luffy and his crew set out on their adventures, others join the crew later in the series, including Tony Tony Chopper, an anthropomorphized reindeer doctor; Nico Robin, an archaeologist and former Baroque Works assassin; Franky, a cyborg shipwright; Brook, a skeleton musician and swordsman; and Jimbei, a whale shark-type fish-man and former member of the Seven Warlords of the Sea who becomes their helmsman. Together, they encounter other pirates, bounty hunters, criminal organizations, revolutionaries, secret agents, different types of scientists, soldiers of the morally-ambiguous World Government, and various other friends and foes, as they sail the seas in pursuit of their dreams.

Production[edit]

Concept and creation[edit]

Eiichiro Oda's interest in pirates began in his childhood, watching the animated series Vicky the Viking, which inspired him to want to draw a manga series about pirates.[2] The reading of pirate biographies influenced Oda to incorporate the characteristics of real-life pirates into many of the characters in One Piece; for example, the character Marshall D. Teach is based on and named after the historical pirate Edward "Blackbeard" Teach.[3] Apart from the history of piracy, Oda's biggest influence is Akira Toriyama and his series Dragon Ball, which is one of his favorite manga.[4] He was also inspired by The Wizard of Oz, claiming not to endure stories where the reward of adventure is the adventure itself, opting for a story where travel is important, but even more important is the goal.[5]

While working as an assistant to Nobuhiro Watsuki, Oda began writing One Piece in 1996.[6] It started as two one-shot stories entitled Romance Dawn[6]—which would later be used as the title for One Piece's first chapter and volume. They both featured the character of Luffy, and included elements that would appear later in the main series. The first of these short stories was published in August 1996 in Akamaru Jump, and reprinted in 2002 in One Piece Red guidebook. The second was published in the 41st issue of Weekly Shōnen Jump in 1996, and reprinted in 1998 in Oda's short story collection, Wanted![7] In an interview with TBS, Takanori Asada, the original editor of One Piece, revealed that the manga was rejected by Weekly Shōnen Jump three times before Shueisha agreed to publish the series.[8]

Development[edit]

Oda's primary inspiration for the concept of Devil Fruits was Doraemon; the Fruits' abilities and uses reflect Oda's daily life and his personal fantasies, similar to that of Doraemon's gadgets, such as the Gum-Gum Fruit being inspired by Oda's laziness.[9] When designing the outward appearance of Devil Fruits Oda thinks of something that would fulfill a human desire; he added that he does not see why he would draw a Devil Fruit unless the fruit's appearance would entice one to eat it.[10] The names of many special attacks, as well as other concepts in the manga, consist of a form of punning in which phrases written in kanji are paired with an idiosyncratic reading. The names of some characters' techniques are often mixed with other languages, and the names of several of Zoro's sword techniques are designed as jokes; they look fearsome when read by sight but sound like kinds of food when read aloud. For example, Zoro's signature move is Onigiri, which is written as demon cut but is pronounced the same as rice ball in Japanese. Eisaku Inoue, the animation director, has said that the creators did not use these kanji readings in the anime since they "might have cut down the laughs by about half".[11] Nevertheless, Konosuke Uda, the director, said that he believes that the creators "made the anime pretty close to the manga".[11]

Oda was "sensitive" about how his work would be translated.[12] In many instances, the English version of the One Piece manga uses one onomatopoeia for multiple onomatopoeia used in the Japanese version. For instance, "saaa" (the sound of light rain, close to a mist) and "zaaa" (the sound of pouring rain) are both translated as "fshhhhhhh".[13] Unlike other manga artists, Oda draws everything that moves himself to create a consistent look while leaving his staff to draw the backgrounds based on sketches he has drawn.[14] This workload forces him to keep tight production rates, starting from five in the morning until two in the morning the next day, with short breaks only for meals. Oda's work program includes the first three days of the week dedicated to the writing of the storyboard and the remaining time for the definitive inking of the boards and for the possible coloring.[15] When a reader asked who Nami was in love with, Oda replied that there would hardly be any love affairs within Luffy's crew. The author also explained he deliberately avoids including them in One Piece since the series is a shōnen manga and the boys who read it are not interested in love stories.[16]

Conclusion[edit]

Oda revealed that he originally planned One Piece to last five years, and that he had already planned the ending. However, he found it would take longer than he had expected as Oda realized that he liked the story too much to end it in that period of time.[17] In 2016, nineteen years after the start of serialization, the author said that the manga has reached 65% of the story he intends to tell.[18] In July 2018, on the occasion of the twenty-first anniversary of One Piece, Oda said that the manga has reached 80% of the plot,[19] while in January 2019, he said that One Piece is on its way to the conclusion, but that it could exceed the 100th volume.[20] In August 2019, Oda said that, according to his predictions, the manga will end between 2024 and 2025.[21] However, Oda stated that the ending would be what he had decided in the beginning; he is committed to seeing it through.[22] In a television special aired in Japan, Oda said he would be willing to change the ending if the fans were to be able to predict it.[5] In August 2020, Shueisha announced in the year's 35th issue of Weekly Shōnen Jump that One Piece was "headed toward the upcoming final saga."[23] On January 4, 2021, One Piece reached its thousandth chapter.[24][25][26] In June 2022, Oda announced that the manga would enter a one-month break to prepare for its 25th anniversary and its final saga, set to begin with the release of chapter 1054.[27]

Media[edit]

Manga[edit]

Written and illustrated by Eiichiro Oda, One Piece has been serialized by Shueisha in the shōnen manga anthology Weekly Shōnen Jump since July 22, 1997.[28][29] Shueisha has collected its chapters into individual tankōbon volumes. The first volume was released on December 24, 1997.[30] By March 4, 2024, a total of 108 volumes have been released.[31]

The first English translation of One Piece was released by Viz Media in November 2002, who published its chapters in the manga anthology Shonen Jump, and later collected in volumes since June 30, 2003.[32][33][34] In 2009, Viz announced the release of five volumes per month during the first half of 2010 to catch up with the serialization in Japan.[35] Following the discontinuation of the print Shonen Jump, Viz began releasing One Piece chapterwise in its digital successor Weekly Shonen Jump on January 30, 2012.[36] Following the digital Weekly Shonen Jump's cancelation in December 2018, Viz Media started simultaneously publishing One Piece through its Shonen Jump service, and by Shueisha through Manga Plus, in January 2019.[37][38]

In the United Kingdom, the volumes were published by Gollancz Manga, starting in March 2006,[39] until Viz Media took it over after the fourteenth volume.[40][41] In Australia and New Zealand, the English volumes have been distributed by Madman Entertainment since November 10, 2008.[42] In Poland, Japonica Polonica Fantastica is publishing the manga,[43] Glénat in France,[44] Panini Comics in Mexico,[45] LARP Editores and later by Ivrea in Argentina,[46][47] Planeta de Libros in Spain,[48] Edizioni Star Comics in Italy,[49] and Sangatsu Manga in Finland.[50]

Spin-offs and crossovers[edit]

Oda teamed up with Akira Toriyama to create a single crossover of One Piece and Toriyama's Dragon Ball. Entitled Cross Epoch, the one-shot was published in the December 25, 2006, issue of Weekly Shōnen Jump and the April 2011 issue of the English Shonen Jump.[51] Oda collaborated with Mitsutoshi Shimabukuro, author of Toriko, for a crossover one-shot of their series titled Taste of the Devil Fruit (実食! 悪魔の実!!, Jitsushoku! Akuma no Mi!!, lit. 'The True Food! Devil Fruit!!'),[52] which ran in the April 4, 2011, issue of Weekly Shōnen Jump. The spin-off series One Piece Party (ワンピースパーティー, Wan Pīsu Pātī), written by Ei Andō in a super deformed art style, began serialization in the January 2015 issue of Saikyō Jump.[53] Its final chapter was published on Shōnen Jump+ on February 2, 2021.[54]

Anime[edit]

Festival films and original video animation[edit]

One Piece: Defeat Him! The Pirate Ganzack! was produced by Production I.G for the 1998 Jump Super Anime Tour and was directed by Gorō Taniguchi.[55] Luffy, Nami, and Zoro are attacked by a sea monster that destroys their boat and separates them. Luffy is found on an island beach, where he saves a little girl, Medaka, from two pirates. All the villagers, including Medaka's father have been abducted by Ganzack and his crew and forced into labor. After hearing that Ganzack also stole all the food, Luffy and Zoro rush out to retrieve it. As they fight the pirates, one of them kidnaps Medaka. A fight starts between Luffy and Ganzack, ending with Luffy's capture. Meanwhile, Zoro is forced to give up after a threat is made to kill all the villagers. They rise up against Ganzack, and while the islanders and pirates fight, Nami unlocks the three captives. Ganzack defeats the rebellion and reveals his armored battleship. The Straw Hat Pirates are forced to fight Ganzack once more to prevent him from destroying the island.

A second film, One Piece: Romance Dawn Story, was produced by Toei Animation in July 2008 for the Jump Super Anime Tour. It is 34 minutes in length and based on the first version of Romance Dawn.[56][7] It includes the Straw Hat Pirates up to Brook and their second ship, the Thousand Sunny. In search for food for his crew, Luffy arrives at a port after defeating a pirate named Crescent Moon Gally on the way. There he meets a girl named Silk, who was abandoned by attacking pirates as a baby and raised by the mayor. Her upbringing causes her to value the town as her "treasure". The villagers mistake Luffy for Gally and capture him just as the real Gally returns. Gally throws Luffy in the water and plans to destroy the town, but Silk saves him and Luffy pursues Gally. His crew arrives to help him, and with their help he recovers the treasure for the town, acquires food, and destroys Gally's ship. The film was later released as a triple feature DVD with Dragon Ball: Yo! Son Goku and His Friends Return!! and Tegami Bachi: Light and Blue Night, that was available only though a mail-in offer exclusively to Japanese residents.[57]

The One Piece Film Strong World: Episode 0 original video animation adapts the manga's special "Chapter 0", which shows how things were before and after the death of Roger. It received a limited release of three thousand DVDs as a collaboration with the House Foods brand.[58]

1999 TV series[edit]

An anime television series adaptation produced by Toei Animation premiered on Fuji Television on October 20, 1999;[59] the series reached its 1,000th episode in November 2021.[60]

Upcoming TV series[edit]

In December 2023 at the Jump Festa '24 event, it was announced that Wit Studio would be producing an anime series remake for Netflix, restarting from the East Blue story arc, to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the original anime series. The remake will be titled The One Piece.[61]

Theatrical films[edit]

Fourteen animated theatrical films based on the One Piece series have been released. The films are typically released in March to coincide with the spring vacation of Japanese schools.[62] The films feature self-contained, completely original plots, or alternate retellings of story arcs with animation of a higher quality than what the weekly anime allows. The first three films were typically double features paired up with other anime films, and were thus usually an hour or less in length. The films themselves offer contradictions in both chronology and design that make them incompatible with a single continuity. Funimation has licensed the eighth, tenth, and twelfth films for release in North America, and these films have received in-house dubs by the company.[63][64]

Live-action series[edit]

On July 21, 2017, Weekly Shōnen Jump editor-in-chief Hiroyuki Nakano announced that Tomorrow Studios (a partnership between Marty Adelstein and ITV Studios) and Shueisha would commence production of an American live-action television adaptation of Eiichiro Oda's One Piece manga series as part of the series' 20th anniversary celebrations.[65][66] Eiichiro Oda served as executive producer for the series alongside Tomorrow Studios CEO Adelstein and Becky Clements.[66] The series would reportedly begin with the East Blue arc.[67]

In January 2020, Oda revealed that Netflix ordered a first season consisting of ten episodes.[68] On May 19, 2020, producer Marty Adelstein revealed during an interview with SyFy Wire, that the series was originally set to begin filming in Cape Town sometime around August, but has since been delayed to around September due to COVID-19. He also revealed that, during the same interview, all ten scripts had been written for the series and they were set to begin casting sometime in June.[69] However, executive producer Matt Owens stated in September 2020 that casting had not yet commenced.[70] On September 15, 2023, Oda revealed that the show has been renewed for the second season.[71]

In March 2021, production started up again with showrunner Steven Maeda revealing that the series codename is Project Roger.[72] In November 2021, it was announced that the casting for the series includes Iñaki Godoy as Monkey D. Luffy, Mackenyu as Roronoa Zoro, Emily Rudd as Nami, Jacob Romero Gibson as Usopp and Taz Skylar as Sanji.[73][74] In March 2022, Netflix added Morgan Davies as Koby, Ilia Isorelýs Paulino as Alvida, Aidan Scott as Helmeppo, Jeff Ward as Buggy, McKinley Belcher III as Arlong, Vincent Regan as

Simpsons #4

The Simpsons theme by jéjé

Download: Simpsons_4.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

Redirect to:

This page is a redirect. The following categories are used to track and monitor this redirect:

|

Dragonball Z #3

Superman

Superman theme by Clark Kent

Download: Superman.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

| Clark Kent / Kal-El Superman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | DC Comics |

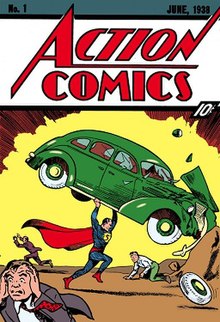

| First appearance | Action Comics #1 (cover-dated June 1938; published April 18, 1938) |

| Created by | Jerry Siegel (writer) Joe Shuster (artist) |

| In-story information | |

| Alter ego | Kal-El (birth name) Clark J. Kent (adopted name) |

| Species | Kryptonian |

| Place of origin | Krypton |

| Team affiliations | |

| Partnerships |

|

| Notable aliases |

|

| Abilities |

|

Superman is a superhero who appears in American comic books published by DC Comics. The character was created by writer Jerry Siegel and artist Joe Shuster, and debuted in the comic book Action Comics #1 (cover-dated June 1938 and published April 18, 1938).[1] Superman has been adapted to a number of other media, which includes radio serials, novels, films, television shows, theater, and video games.

Superman was born on the fictional planet Krypton with the birth name of Kal-El. As a baby, his parents sent him to Earth in a small spaceship shortly before Krypton was destroyed in a natural cataclysm. His ship landed in the American countryside near the fictional town of Smallville, Kansas. He was found and adopted by farmers Jonathan and Martha Kent, who named him Clark Kent. Clark began developing various superhuman abilities, such as incredible strength and impervious skin. His adoptive parents advised him to use his powers for the benefit of humanity, and he decided to fight crime as a vigilante. To protect his personal life, he changes into a colorful costume and uses the alias "Superman" when fighting crime. Clark resides in the fictional American city of Metropolis, where he works as a journalist for the Daily Planet. Superman's supporting characters include his love interest and fellow journalist Lois Lane, Daily Planet photographer Jimmy Olsen, and editor-in-chief Perry White, and his enemies include Brainiac, General Zod, and archenemy Lex Luthor.

Superman is the archetype of the superhero: he wears an outlandish costume, uses a codename, and fights evil with the aid of extraordinary abilities. Although there are earlier characters who arguably fit this definition, it was Superman who popularized the superhero genre and established its conventions. He was the best-selling superhero in American comic books up until the 1980s.[2]

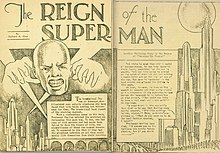

Development[edit]

Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster met in 1932 while attending Glenville High School in Cleveland and bonded over their admiration of fiction. Siegel aspired to become a writer and Shuster aspired to become an illustrator. Siegel wrote amateur science fiction stories, which he self-published as a magazine called Science Fiction: The Advance Guard of Future Civilization. His friend Shuster often provided illustrations for his work.[3] In January 1933, Siegel published a short story in his magazine titled "The Reign of the Superman". The titular character is a homeless man named Bill Dunn who is tricked by an evil scientist into consuming an experimental drug. The drug gives Dunn the powers of mind-reading, mind-control, and clairvoyance. He uses these powers maliciously for profit and amusement, but then the drug wears off, leaving him a powerless vagrant again. Shuster provided illustrations, depicting Dunn as a bald man.[4]

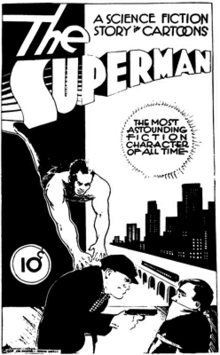

Siegel and Shuster shifted to making comic strips, with a focus on adventure and comedy. They wanted to become syndicated newspaper strip authors, so they showed their ideas to various newspaper editors. However, the newspaper editors told them that their ideas were insufficiently sensational. If they wanted to make a successful comic strip, it had to be something more sensational than anything else on the market. This prompted Siegel to revisit Superman as a comic strip character.[5][6] Siegel modified Superman's powers to make him even more sensational: Like Bill Dunn, the second prototype of Superman is given powers against his will by an unscrupulous scientist, but instead of psychic abilities, he acquires superhuman strength and bullet-proof skin.[7][8] Additionally, this new Superman was a crime-fighting hero instead of a villain, because Siegel noted that comic strips with heroic protagonists tended to be more successful.[9] In later years, Siegel once recalled that this Superman wore a "bat-like" cape in some panels, but typically he and Shuster agreed there was no costume yet, and there is none apparent in the surviving artwork.[10][11]

Siegel and Shuster showed this second concept of Superman to Consolidated Book Publishers, based in Chicago.[12][a] In May 1933, Consolidated had published a proto-comic book titled Detective Dan: Secret Operative 48.[13] It contained all-original stories as opposed to reprints of newspaper strips, which was a novelty at the time.[14] Siegel and Shuster put together a comic book in a similar format called The Superman. A delegation from Consolidated visited Cleveland that summer on a business trip and Siegel and Shuster took the opportunity to present their work in person.[15][16] Although Consolidated expressed interest, they later pulled out of the comics business without ever offering a book deal because the sales of Detective Dan were disappointing.[17][18]

Siegel believed publishers kept rejecting them because he and Shuster were young and unknown, so he looked for an established artist to replace Shuster.[19] When Siegel told Shuster what he was doing, Shuster reacted by burning their rejected Superman comic, sparing only the cover. They continued collaborating on other projects, but for the time being Shuster was through with Superman.[20]

Siegel wrote to numerous artists.[19] The first response came in July 1933 from Leo O'Mealia, who drew the Fu Manchu strip for the Bell Syndicate.[21][22] In the script that Siegel sent to O'Mealia, Superman's origin story changes: He is a "scientist-adventurer" from the far future when humanity has naturally evolved "superpowers". Just before the Earth explodes, he escapes in a time-machine to the modern era, whereupon he immediately begins using his superpowers to fight crime.[23] O'Mealia produced a few strips and showed them to his newspaper syndicate, but they were rejected. O'Mealia did not send to Siegel any copies of his strips, and they have been lost.[24]

In June 1934, Siegel found another partner: an artist in Chicago named Russell Keaton.[25][26] Keaton drew the Buck Rogers and Skyroads comic strips. In the script that Siegel sent Keaton in June, Superman's origin story further evolved: In the distant future, when Earth is on the verge of exploding due to "giant cataclysms", the last surviving man sends his three-year-old son back in time to the year 1935. The time-machine appears on a road where it is discovered by motorists Sam and Molly Kent. They leave the boy in an orphanage, but the staff struggle to control him because he has superhuman strength and impenetrable skin. The Kents adopt the boy and name him Clark, and teach him that he must use his fantastic natural gifts for the benefit of humanity. In November, Siegel sent Keaton an extension of his script: an adventure where Superman foils a conspiracy to kidnap a star football player. The extended script mentions that Clark puts on a special "uniform" when assuming the identity of Superman, but it is not described.[27] Keaton produced two weeks' worth of strips based on Siegel's script. In November, Keaton showed his strips to a newspaper syndicate, but they too were rejected, and he abandoned the project.[28][29]

Siegel and Shuster reconciled and resumed developing Superman together. The character became an alien from the planet Krypton. Shuster designed the now-familiar costume: tights with an "S" on the chest, over-shorts, and a cape.[30][31][32] They made Clark Kent a journalist who pretends to be timid, and conceived his colleague Lois Lane, who is attracted to the bold and mighty Superman but does not realize that he and Kent are the same person.[33]

In June 1935 Siegel and Shuster finally found work with National Allied Publications, a comic magazine publishing company in New York owned by Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson.[35] Wheeler-Nicholson published two of their strips in New Fun Comics #6 (1935): "Henri Duval" and "Doctor Occult".[36] Siegel and Shuster also showed him Superman and asked him to market Superman to the newspapers on their behalf.[37] In October, Wheeler-Nicholson offered to publish Superman in one of his own magazines.[38] Siegel and Shuster refused his offer because Wheeler-Nicholson had demonstrated himself to be an irresponsible businessman. He had been slow to respond to their letters and had not paid them for their work in New Fun Comics #6. They chose to keep marketing Superman to newspaper syndicates themselves.[39][40] Despite the erratic pay, Siegel and Shuster kept working for Wheeler-Nicholson because he was the only publisher who was buying their work, and over the years they produced other adventure strips for his magazines.[41]

Wheeler-Nicholson's financial difficulties continued to mount. In 1936, he formed a joint corporation with Harry Donenfeld and Jack Liebowitz called Detective Comics, Inc. in order to release his third magazine, which was titled Detective Comics. Siegel and Shuster produced stories for Detective Comics too, such as "Slam Bradley". Wheeler-Nicholson fell into deep debt to Donenfeld and Liebowitz, and in early January 1938, Donenfeld and Liebowitz petitioned Wheeler-Nicholson's company into bankruptcy and seized it.[3][42]

In early December 1937, Siegel visited Liebowitz in New York, and Liebowitz asked Siegel to produce some comics for an upcoming comic anthology magazine called Action Comics.[43][44] Siegel proposed some new stories, but not Superman. Siegel and Shuster were, at the time, negotiating a deal with the McClure Newspaper Syndicate for Superman. In early January 1938, Siegel had a three-way telephone conversation with Liebowitz and an employee of McClure named Max Gaines. Gaines informed Siegel that McClure had rejected Superman, and asked if he could forward their Superman strips to Liebowitz so that Liebowitz could consider them for Action Comics. Siegel agreed.[45] Liebowitz and his colleagues were impressed by the strips, and they asked Siegel and Shuster to develop the strips into 13 pages for Action Comics.[46] Having grown tired of rejections, Siegel and Shuster accepted the offer. At least now they would see Superman published.[47][48] Siegel and Shuster submitted their work in late February and were paid $130 (equivalent to $2,814 in 2023) for their work ($10 per page).[49] In early March they signed a contract at Liebowitz's request in which they gave away the copyright for Superman to Detective Comics, Inc. This was normal practice in the business, and Siegel and Shuster had given away the copyrights to their previous works as well.[50]

The duo's revised version of Superman appeared in the first issue of Action Comics, which was published on April 18, 1938. The issue was a huge success thanks to Superman's feature.[1][51][52]

Influences[edit]

Siegel and Shuster read pulp science-fiction and adventure magazines, and many stories featured characters with fantastical abilities such as telepathy, clairvoyance, and superhuman strength. One character in particular was John Carter of Mars from the novels by Edgar Rice Burroughs. John Carter is a human who is transported to Mars, where the lower gravity makes him stronger than the natives and allows him to leap great distances.[53][54] Another influence was Philip Wylie's 1930 novel Gladiator, featuring a protagonist named Hugo Danner who had similar powers.[55][56]

Superman's stance and devil-may-care attitude were influenced by the characters of Douglas Fairbanks, who starred in adventure films such as The Mark of Zorro and Robin Hood.[57] The name of Superman's home city, Metropolis, was taken from the 1927 film of the same name.[58] Popeye cartoons were also an influence.[58]

Clark Kent's harmless facade and dual identity were inspired by the protagonists of such movies as Don Diego de la Vega in The Mark of Zorro and Sir Percy Blakeney in The Scarlet Pimpernel. Siegel thought this would make for interesting dramatic contrast and good humor.[59][60] Another inspiration was slapstick comedian Harold Lloyd. The archetypal Lloyd character was a mild-mannered man who finds himself abused by bullies but later in the story snaps and fights back furiously.[61]

Kent is a journalist because Siegel often imagined himself becoming one after leaving school. The love triangle between Lois Lane, Clark, and Superman was inspired by Siegel's own awkwardness with girls.[62]

The pair collected comic strips in their youth, with a favorite being Winsor McCay's fantastical Little Nemo.[58] Shuster remarked on the artists who played an important part in the development of his own style: "Alex Raymond and Burne Hogarth were my idols – also Milt Caniff, Hal Foster, and Roy Crane."[58] Shuster taught himself to draw by tracing over the art in the strips and magazines they collected.[3]

As a boy, Shuster was interested in fitness culture[63] and a fan of strongmen such as Siegmund Breitbart and Joseph Greenstein. He collected fitness magazines and manuals and used their photographs as visual references for his art.[3]

The visual design of Superman came from multiple influences. The tight-fitting suit and shorts were inspired by the costumes of wrestlers, boxers, and strongmen. In early concept art, Shuster gave Superman laced sandals like those of strongmen and classical heroes, but these were eventually changed to red boots.[34] The costumes of Douglas Fairbanks were also an influence.[64] The emblem on his chest was inspired by heraldic crests.[65] Many pulp action heroes such as swashbucklers wore capes. Superman's face was based on Johnny Weissmuller with touches derived from the comic-strip character Dick Tracy and from the work of cartoonist Roy Crane.[66]

The word "superman" was commonly used in the 1920s and 1930s to describe men of great ability, most often athletes and politicians.[67] It occasionally appeared in pulp fiction stories as well, such as "The Superman of Dr. Jukes".[68] It is unclear whether Siegel and Shuster were influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche's concept of the Übermensch; they never acknowledged as much.[69]

Comics[edit]

Comic books[edit]

Since 1938, Superman stories have been regularly published in periodical comic books published by DC Comics. The first and oldest of these is Action Comics, which began in April 1938.[1] Action Comics was initially an anthology magazine, but it eventually became dedicated to Superman stories. The second oldest periodical is Superman, which began in June 1939. Action Comics and Superman have been published without interruption (ignoring changes to the title and numbering scheme).[71][72] A number of other shorter-lived Superman periodicals have been published over the years.[73] Superman is part of the DC Universe, which is a shared setting of superhero characters owned by DC Comics, and consequently he frequently appears in stories alongside the likes of Batman, Wonder Woman, and others.

Superman has sold more comic books over his publication history than any other American superhero character.[74] Exact sales figures for the early decades of Superman comic books are hard to find because, like most publishers at the time, DC Comics concealed this data from its competitors and thereby the general public as well, but given the general market trends at the time, sales of Action Comics and Superman probably peaked in the mid-1940s and thereafter steadily declined.[75] Sales data first became public in 1960, and showed that Superman was the best-selling comic book character of the 1960s and 1970s.[2][76][77] Sales rose again starting in 1987. Superman #75 (Nov 1992) sold over 23 million copies,[78] making it the best-selling issue of a comic book of all time, thanks to a media sensation over the supposedly permanent death of the character in that issue.[79] Sales declined from that point on. In March 2018, Action Comics sold just 51,534 copies, although such low figures are normal for superhero comic books in general (for comparison, Amazing Spider-Man #797 sold only 128,189 copies).[80] The comic books are today considered a niche aspect of the Superman franchise due to low readership,[81] though they remain influential as creative engines for the movies and television shows. Comic book stories can be produced quickly and cheaply, and are thus an ideal medium for experimentation.[82]

Whereas comic books in the 1950s were read by children, since the 1990s the average reader has been an adult.[83] A major reason for this shift was DC Comics' decision in the 1970s to sell its comic books to specialty stores instead of traditional magazine retailers (supermarkets, newsstands, etc.) — a model called "direct distribution". This made comic books less accessible to children.[84]

Newspaper strips[edit]

Beginning in January 1939, a Superman daily comic strip appeared in newspapers, syndicated through the McClure Syndicate. A color Sunday version was added that November. Jerry Siegel wrote most of the strips until he was conscripted in 1943. The Sunday strips had a narrative continuity separate from the daily strips, possibly because Siegel had to delegate the Sunday strips to ghostwriters.[85] By 1941, the newspaper strips had an estimated readership of 20 million.[86] Joe Shuster drew the early strips, then passed the job to Wayne Boring.[87] From 1949 to 1956, the newspaper strips were drawn by Win Mortimer.[88] The strip ended in May 1966, but was revived from 1977 to 1983 to coincide with a series of movies released by Warner Bros.[89]

Editors[edit]

Initially, Siegel was allowed to write Superman more or less as he saw fit because nobody had anticipated the success and rapid expansion of the franchise.[90][91] But soon Siegel and Shuster's work was put under careful oversight for fear of trouble with censors.[92] Siegel was forced to tone down the violence and social crusading that characterized his early stories.[93] Editor Whitney Ellsworth, hired in 1940, dictated that Superman not kill.[94] Sexuality was banned, and colorfully outlandish villains such as Ultra-Humanite and Toyman were thought to be less nightmarish for young readers.[95]

Mort Weisinger was the editor on Superman comics from 1941 to 1970, his tenure briefly interrupted by military service. Siegel and his fellow writers had developed the character with little thought of building a coherent mythology, but as the number of Superman titles and the pool of writers grew, Weisinger demanded a more disciplined approach.[96] Weisinger assigned story ideas, and the logic of Superman's powers, his origin, the locales, and his relationships with his growing cast of supporting characters were carefully planned. Elements such as Bizarro, his cousin Supergirl, the Phantom Zone, the Fortress of Solitude, alternate varieties of kryptonite, robot doppelgangers, and Krypto were introduced during this era. The complicated universe built under Weisinger was beguiling to devoted readers but alienating to casuals.[97] Weisinger favored lighthearted stories over serious drama, and avoided sensitive subjects such as the Vietnam War and the American civil rights movement because he feared his right-wing views would alienate his left-leaning writers and readers.[98] Weisinger also introduced letters columns in 1958 to encourage feedback and build intimacy with readers.[99]

Weisinger retired in 1970 and Julius Schwartz took over. By his own admission, Weisinger had grown out of touch with newer readers.[100] Starting with The Sandman Saga, Schwartz updated Superman by making Clark Kent a television anchor, and he retired overused plot elements such as kryptonite and robot doppelgangers.[101] Schwartz also scaled Superman's powers down to a level closer to Siegel's original. These changes would eventually be reversed by later writers. Schwartz allowed stories with serious drama such as "For the Man Who Has Everything" (Superman Annual #11), in which the villain Mongul torments Superman with an illusion of happy family life on a living Krypton.

Schwartz retired from DC Comics in 1986 and was succeeded by Mike Carlin as an editor on Superman comics. His retirement coincided with DC Comics' decision to reboot the DC Universe with the companywide-crossover storyline "Crisis on Infinite Earths". In The Man of Steel writer John Byrne rewrote the Superman mythos, again reducing Superman's powers, which writers had slowly re-strengthened, and revised many supporting characters, such as making Lex Luthor a billionaire industrialist rather than a mad scientist, and making Supergirl an artificial shapeshifting organism because DC wanted Superman to be the sole surviving Kryptonian.

Carlin was promoted to Executive Editor for the DC Universe books in 1996, a position he held until 2002. K.C. Carlson took his place as editor of the Superman comics.

Aesthetic style[edit]

In the earlier decades of Superman comics, artists were expected to conform to a certain "house style".[102] Joe Shuster defined the

Please Teacher

Cowboy Bebop

Cowboy Bebop theme by V4oLDbOY

Download: CowboyBebop.p3t

(6 backgrounds)

| Cowboy Bebop | |

Key visual of the series, featuring the entire Bebop crew | |

| カウボーイビバップ (Kaubōi Bibappuu) | |

|---|---|

| Genre | |

| Created by | Hajime Yatate |

| Manga | |

| Cowboy Bebop: Shooting Star | |

| Illustrated by | Cain Kuga |

| Published by | Kadokawa Shoten |

| English publisher | |

| Magazine | Monthly Asuka Fantasy DX |

| Demographic | Shōjo |

| Original run | September 18, 1997 – June 18, 1998 |

| Volumes | 2 |

| Anime television series | |

| Directed by | Shinichirō Watanabe |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by | Keiko Nobumoto |

| Music by | Yoko Kanno |

| Studio | Sunrise |

| Licensed by | Crunchyroll LLC[c] |

| Original network | TXN (TV Tokyo), Wowow |

| English network | |

| Original run | TV Tokyo broadcast April 3, 1998 – June 26, 1998 Wowow broadcast October 23, 1998 – April 24, 1999 |

| Episodes | 26 |

| Manga | |

| Illustrated by | Yutaka Nanten |

| Published by | Kadokawa Shoten |

| English publisher |

|

| Magazine | Monthly Asuka Fantasy DX |

| Demographic | Shōjo |

| Original run | October 18, 1998 – February 18, 2000 |

| Volumes | 3 |

| Anime film | |

| |

| Live-action television series | |

| |

Cowboy Bebop (Japanese: カウボーイビバップ, Hepburn: Kaubōi Bibappu) is a Japanese neo-noir space Western[12] anime television series which aired on TV Tokyo and Wowow from 1998 to 1999. It was created and animated by Sunrise, led by a production team of director Shinichirō Watanabe, screenwriter Keiko Nobumoto, character designer Toshihiro Kawamoto, mechanical designer Kimitoshi Yamane, and composer Yoko Kanno, who are collectively billed as Hajime Yatate.

The series, which ran for twenty-six episodes (dubbed "sessions"), is set in the year 2071, and follows the lives of a traveling bounty-hunting crew aboard a spaceship, the Bebop. Although it incorporates a wide variety of genres, the series draws most heavily from science fiction, Western, and noir films. Its most prominent themes are existential boredom, loneliness, and the inability to escape one's past.

The series was dubbed into English by Animaze and ZRO Limit Productions, and was originally licensed in North America by Bandai Entertainment (and is now licensed by Crunchyroll) and in Britain by Beez Entertainment (now by Anime Limited); Madman Entertainment owns the license in Australia and New Zealand. In 2001, it became the first anime title to be broadcast on Adult Swim.

Cowboy Bebop has been hailed as one of the best animated television series of all time. It was a critical and commercial success both in Japanese and international markets, most notably in the United States. It garnered several major anime and science-fiction awards upon its release, and received acclaim from critics and audiences for its style, characters, story, voice acting, animation, and soundtrack. The English dub was particularly lauded and is regarded as one of the best anime English dubs.[13] Credited with helping to introduce anime to a new wave of Western viewers in the early 2000s, Cowboy Bebop has also been called a gateway series for anime as a whole.[14]

Plot[edit]

In the year 2071, roughly fifty years after an accident with a hyperspace gateway that made Earth almost uninhabitable, humanity has colonized most of the rocky planets and moons of the Solar System. Amid a rising crime rate, the Inter Solar System Police (ISSP) set up a legalized contract system, in which registered bounty hunters (also referred to as "Cowboys") chase criminals and bring them in alive in return for a reward.[15] The series' protagonists are bounty-hunters working from the spaceship Bebop. The original crew is Spike Spiegel, an exiled former hitman of the criminal Red Dragon Syndicate, and Jet Black, a former ISSP officer. They are later joined by Faye Valentine, an amnesiac con artist; Edward, an eccentric child, skilled in hacking; and Ein, a genetically-engineered Pembroke Welsh Corgi with human-like intelligence. Throughout the series, the team gets involved in disastrous mishaps leaving them without money, while often confronting faces and events from their past:[16] These include Jet's reasons for leaving the ISSP and Faye's past as a young woman from Earth injured in an accident and cryogenically frozen to save her life.

While much of the show is episodic, the main story arc focuses on Spike and his deadly rivalry with Vicious, an ambitious criminal affiliated with the Red Dragon Syndicate. Spike and Vicious were once partners and friends. Still, when Spike begins an affair with Vicious's girlfriend Julia and resolves to leave the Syndicate with her, Vicious seeks to eliminate Spike by blackmailing Julia into killing him. Julia hides to protect herself and Spike, while Spike fakes his death to escape the Syndicate. In the present, Julia comes out of hiding and reunites with Spike, intending to complete their plan. Vicious, having staged a coup d'état and taken over the Syndicate, sends hitmen after the pair. Julia is killed, leaving Spike alone. Spike leaves the Bebop after finally apologizing to Faye and Jet. Upon infiltrating the syndicate, he finds Vicious on the top floor of the building and confronts him after dispatching the remaining Red Dragon members. The final battle ends with Spike killing Vicious, only to be seriously wounded himself in the ensuing confrontation. Looking up to the sky, Spike sees Julia. The series concludes as Spike descends the main staircase of the building into the rising sun before eventually falling to the ground.

Genre and themes[edit]

Watanabe created a special tagline for the series to promote it during its original presentation, calling it "a new genre unto itself". The line was inserted before and after commercial breaks during its Japanese and US broadcasts. Later, Watanabe called the phrase an "exaggeration".[17] The show is a hybrid of multiple genres, including westerns and pulp fiction.[18] One reviewer described it as "space opera meets noir, meets comedy, meets cyberpunk".[19][6] It has also been called a "genre-busting space Western".[20][21]

The musical style was emphasized in many of the episode titles.[22][23][24] Multiple philosophical themes are explored using the characters, including existentialism, existential boredom, loneliness, and the effect of the past on the protagonists.[16][25] Other concepts referenced include environmentalism and capitalism.[26] The series also makes specific references to or pastiches multiple films, including the works of John Woo and Bruce Lee, Midnight Run, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Alien.[23][27][28] The series also includes extensive references and elements from science fiction, bearing strong similarities to the cyberpunk fiction of William Gibson.[29] Several planets and space stations in the series are made in Earth's image. The streets of celestial objects such as Ganymede resemble a modern port city, while Mars features shopping malls, theme parks, casinos and cities. [27] This setting has been described as "one part Chinese diaspora and two parts wild west".[18]

Characters[edit]

The characters were created by Watanabe and character designed by Toshihiro Kawamoto. Watanabe envisioned each character as an extension of his own personality, or as an opposite person to himself.[30] Each character, from the main cast to supporting characters, were designed to be outlaws unable to fit into society.[31] Kawamoto designed the characters so they were easily distinguished from one another.[17] All the main cast are characterized by a deep sense of loneliness or resignation to their fate and past.[17] From the perspective of Brian Camp and Julie Davis, the main characters resemble the main characters of the anime series Lupin III, if only superficially, given their more troubled pasts and more complex personalities.[29]

The show focuses on the character of Spike Spiegel (voiced by Kōichi Yamadera), an iconic space cowboy with green hair and often seen wearing a blue suit, with the overall theme of the series being Spike's past and its karmic effect on him.[32] Spike was portrayed as someone who had lost his expectations for the future, having lost the woman he loved, and so was in a near-constant lethargy.[17] Spike's artificial eye was included as Watanabe wanted his characters to have flaws. He was originally going to be given an eyepatch, but this decision was vetoed by producers.[31][33]

Jet (voiced by Unshō Ishizuka) is shown as someone who lost confidence in his former life and has become cynical about the state of society.[17][32] Spike and Jet were designed to be opposites, with Spike being thin and wearing smart attire, while Jet was bulky and wore more casual clothing.[31] The clothing, which was dark in color, also reflected their states of mind.[17] Faye Valentine, Edward Wong (voiced by Aoi Tada), and Ein joined the crew in later episodes.[32] Their designs were intended to contrast against Spike.[31] Faye was described by her voice actress Megumi Hayashibara as initially being an "ugly" woman, with her defining traits being her liveliness, sensuality and humanity.[33] To emphasize her situation when first introduced, she was compared to Poker Alice, a famous Western figure.[31]

Edward and Ein were the only main characters to have real-life models. The former had her behavior based on the antics of Yoko Kanno as observed by Watanabe when he first met her.[31] While generally portrayed as carefree and eccentric, Edward is motivated by a sense of loneliness after being abandoned by her father.[32] Kawamoto initially based Ein's design on a friend's pet corgi, later getting one himself to use as a motion model.[34][35]

Production[edit]

Cowboy Bebop was developed by animation studio Sunrise and created by Hajime Yatate, the well-known pseudonym for the collective contributions of Sunrise's animation staff. The leader of the series' creative team was director Shinichirō Watanabe, most notable at the time for directing Macross Plus and Mobile Suit Gundam 0083: Stardust Memory. Other leading members of Sunrise's creative team were screenwriter Keiko Nobumoto, character designer Toshihiro Kawamoto, mechanical art designer Kimitoshi Yamane, composer Yoko Kanno, and producers Masahiko Minami and Yoshiyuki Takei. Most of them had previously worked together, in addition to having credits on other popular anime titles. Nobumoto had scripted Macross Plus, Kawamoto had designed the characters for Gundam, and Kanno had composed the music for Macross Plus and The Vision of Escaflowne. Yamane had not worked with Watanabe yet, but his credits in anime included Bubblegum Crisis and The Vision of Escaflowne. Minami joined the project as he wanted to do something different from his previous work on mecha anime.[23][33]

Concept[edit]

Cowboy Bebop was Watanabe's first project as solo director, as he had been co-director in his previous works.[36] His original concept was for a movie, and during production he treated each episode as a miniature movie.[37][38] His main inspiration for Cowboy Bebop was the first series of the anime Lupin III, a crime drama focusing on the exploits of the series' titular character.[23] When developing the series' story, Watanabe began by creating the characters first. He explained, "the first image that occurred to me was one of Spike, and from there I tried to build a story around him, trying to make him cool."[36] While the original dialogue of the series was kept clean to avoid any profanities, its level of sophistication was made appropriate to adults in a criminal environment.[23] Watanabe described Cowboy Bebop as "80% serious story and 20% humorous touch".[39] The comical episodes were harder for the team to write than the serious ones, and though several events in them seemed random, they were carefully planned in advance.[31] Watanabe conceived the series' ending early on, and each episode involving Spike and Vicious was meant to foreshadow their final confrontation. Some of the staff were unhappy about this approach as a continuation of the series would be difficult. While he considered altering the ending, he eventually settled with his original idea. The reason for creating the ending was that Watanabe did not want the series to become like Star Trek, with him being tied to doing it for years.[31]

Development[edit]

The project had initially originated with Bandai's toy division as a sponsor, with the goal of selling spacecraft toys. Watanabe recalled his only instruction was "So long as there's a spaceship in it, you can do whatever you want." But upon viewing early footage, it became clear that Watanabe's vision for the series did not match Bandai's. Believing the series would never sell toy merchandise, Bandai pulled out of the project, leaving it in development hell until sister company Bandai Visual stepped in to sponsor it. Since there was no need to merchandise toys with the property any more, Watanabe had free rein in the development of the series.[36] Watanabe wanted to design not just a space adventure series for adolescent boys but a program that would also appeal to sophisticated adults.[23] During the making of Bebop, Watanabe often attempted to rally the animation staff by telling them that the show would be something memorable up to three decades later. While some of them were doubtful of that at the time, Watanabe many years later expressed his happiness to have been proven right in retrospect. He joked that if Bandai Visual had not intervened then "you might be seeing me working the supermarket checkout counter right now."[36]

The city locations were generally inspired by the cities of New York and Hong Kong.[40] The atmospheres of the planets and the ethnic groups in Cowboy Bebop mostly originated from Watanabe's ideas, with some collaboration from set designers Isamu Imakake, Shoji Kawamori, and Dai Satō. The animation staff established the particular planet atmospheres early in the production of the series before working on the ethnic groups. It was Watanabe who wanted to have several groups of ethnic diversity appear in the series. Mars was the planet most often used in Cowboy Bebop's storylines, with Satoshi Toba, the cultural and setting producer, explaining that the other planets "were unexpectedly difficult to use". He stated that each planet in the series had unique features, and the producers had to take into account the characteristics of each planet in the story. For the final episode, Toba explained that it was not possible for the staff to have the dramatic rooftop scene occur on Venus, so the staff "ended up normally falling back to Mars".[41] In creating the backstory, Watanabe envisioned a world that was "multinational rather than stateless". In spite of certain American influences in the series, he stipulated that the country had been destroyed decades prior to the story, later saying the notion of the United States as the center of the world repelled him.[42]

Music[edit]

The music for Cowboy Bebop was composed by Yoko Kanno.[43] Kanno formed the blues and jazz band Seatbelts to perform the series' music.[44] According to Kanno, the music was one of the first aspects of the series to begin production, before most of the characters, story, or animation had been finalized. The genres she used for its composition were western, opera, and jazz.[31] Watanabe noted that Kanno did not score the music exactly the way he told her to. He stated, "She gets inspired on her own, follows up on her own imagery, and comes to me saying 'this is the song we need for Cowboy Bebop', and composes something completely on her own."[39] Kanno herself was sometimes surprised at how pieces of her music were used in scenes, sometimes wishing it had been used elsewhere, though she also felt that none of their uses were "inappropriate". She was pleased with the working environment, finding the team very relaxed in comparison with other teams she had worked with.[33]

Watanabe further explained that he would take inspiration from Kanno's music after listening to it and create new scenes for the story from it. These new scenes in turn would inspire Kanno and give her new ideas for the music and she would come to Watanabe with even more music. Watanabe cited as an example, "some songs in the second half of the series, we didn't even ask her for those songs, she just made them and brought them to us." He commented that while Kanno's method was normally "unforgivable and unacceptable", it was ultimately a "big hit" with Cowboy Bebop. Watanabe described his collaboration with Kanno as "a game of catch between the two of us in developing the music and creating the TV series Cowboy Bebop".[39][45] Since the series' broadcast, Kanno and the Seatbelts have released seven original soundtrack albums, two singles and EPs, and two compilations through label Victor Entertainment.[46]

Weapons[edit]

The guns on the show were chosen by the director, Watanabe, and in discussion with set designer, Isamu Imakake, and mechanical designer, Kimitoshi Yamane. Setting producer, Satoshi Toba said, "They talked about how they didn't want common guns, because that wouldn't be very interesting, and so they decided on these guns."[47]

Distribution[edit]

Broadcast[edit]

Cowboy Bebop debuted on TV Tokyo, one of the main broadcasters of anime in Japan, airing from April 3 until June 26, 1998.[48] Due to its 6:00 p.m. timeslot[49] and depictions of graphic violence,[50] the show's first run only included episodes 2, 3, 7 to 15, 18 and a special. Later that year, the series was shown in its entirety from October 23 until April 24, 1999, on satellite network Wowow.[51] The full series has also been broadcast across Japan by anime television network Animax, which has also aired the series via its respective networks across Southeast Asia, South Asia and East Asia.

The first non-Asian country to air Cowboy Bebop was Italy. There, it was first aired on October 21, 1999, on MTV, where it inaugurated the 9:00–10:30 p.m. Anime Night programming block.

In the United States, Cowboy Bebop was one of the programs shown when Cartoon Network's late night block Adult Swim debuted on September 2, 2001, being the first anime shown on the block that night at midnight ET.[52] During its original run on Adult Swim, episodes 6, 8, and 22 were skipped due to their violent themes in wake of the September 11 attacks. By the third run of the series, all these episodes had premiered for the first time. Cowboy Bebop was successful enough to be broadcast repeatedly for four years. It has been run at least once every year since 2007, and HD remasters of the show began broadcasting in 2015. In the United Kingdom, it was first broadcast in 2002 on the adult-oriented channel CNX. From November 6, 2007, it was repeated on AnimeCentral until the channel

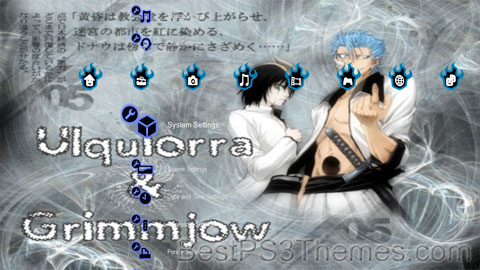

Bleach Red

Bleach Red theme by Black Ops

Download: BleachRed.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

P3T Unpacker v0.12

Copyright (c) 2007. Anoop Menon

This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit!

Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip

Instructions:

Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme.

The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract.

The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename].

For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following:

p3textractor filename.p3t [destination path]Replace filename with the name of the p3t file, and replace [destination path] with the name of the folder you want the files to be extracted to. A destination path is not required. By default it will extract to extracted.filename.

Bleach Blue

Bleach Blue theme by Black Ops

Download: BleachBlue.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

P3T Unpacker v0.12

Copyright (c) 2007. Anoop Menon

This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit!

Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip

Instructions:

Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme.

The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract.

The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename].

For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following:

p3textractor filename.p3t [destination path]Replace filename with the name of the p3t file, and replace [destination path] with the name of the folder you want the files to be extracted to. A destination path is not required. By default it will extract to extracted.filename.

One Piece Complete

One Piece Complete theme by Black Ops

Download: OnePieceComplete.p3t

(4 backgrounds)

P3T Unpacker v0.12

Copyright (c) 2007. Anoop Menon

This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit!

Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip

Instructions:

Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme.

The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract.

The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename].

For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following:

p3textractor filename.p3t [destination path]Replace filename with the name of the p3t file, and replace [destination path] with the name of the folder you want the files to be extracted to. A destination path is not required. By default it will extract to extracted.filename.

RahXephon

RahXephon theme by iCeMaN

Download: RahXephon.p3t

(4 backgrounds)

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (September 2022) |

| RahXephon | |

Cover art from the third volume of ADV's DVD release of RahXephon | |

| ラーゼフォン (Rāzefon) | |

|---|---|

| Genre | Mecha,[1] romance[2] |

| Created by | Bones, Yutaka Izubuchi |

| Manga | |

| Written by | Takeaki Momose |

| Published by | Shogakukan |

| English publisher | |

| Magazine | Monthly Sunday Gene-X |

| Demographic | Seinen |

| Original run | August 19, 2001 – November 19, 2002 |

| Volumes | 3 |

| Anime television series | |

| Directed by | Yutaka Izubuchi |

| Produced by |

|

| Written by |

|

| Music by | Ichiko Hashimoto |

| Studio | Bones |

| Licensed by |

|

| Original network | FNS (Fuji TV) |

| English network | |

| Original run | January 21, 2002 – September 11, 2002 |

| Episodes | 26 |

| Novel series | |

| Written by | Hiroshi Ohnogi |

| Published by | Media Factory |

| English publisher | |

| Imprint | MF Bunko J |

| Demographic | Male |

| Original run | July 2002 – February 2003 |

| Volumes | 5 |

| Video game | |

| Publisher | Bandai |

| Genre | Adventure, Action |

| Platform | PlayStation 2 |

| Released | August 7, 2003 |

| Original video animation | |

| Her and Herself (彼女と彼女自身と) / Thatness and Thereness | |

| Directed by | Tomoki Kyoda |

| Written by | Tomoki Kyoda |

| Music by | Ichiko Hashimoto |

| Studio | Bones |

| Released | August 7, 2003 |

| Runtime | 15 minutes |

| Other | |

RahXephon (Japanese: ラーゼフォン, Hepburn: Rāzefon) is a Japanese anime television series created and directed by Yutaka Izubuchi. The series follows 17-year-old Ayato Kamina, his ability to control a mecha known as the RahXephon, and his inner journey to find a place in the world. His life as a student and artist in Tokyo is suddenly interrupted by a mysterious stalker, strange planes invading the city and strange machines fighting back.

The series was animated by Bones and it aired on Fuji TV for twenty-six episodes from January to September 2002. It was produced by Fuji TV, Bones, Media Factory and Victor Entertainment. The series received critical acclaim and was subsequently translated, released on the DVD and aired in several other countries, including the United States. A 2003 movie adaptation RahXephon: Pluralitas Concentio was directed by Tomoki Kyoda, with plot changes and new scenes. The series was also spun into novels, an extra OVA episode, an audio drama, a video game, illustration books and an altered manga adaptation by Takeaki Momose.

Director Izubuchi said RahXephon was his attempt to set a new standard for mecha anime, as well as to bring back aspects of 1970s mecha shows like Reideen The Brave.

Setting[edit]

The backstory of RahXephon is a fight against multi-dimensional invaders known as Mulians (known as Mu (ムー, Mū)). The Mu are visually indistinguishable from humans, however they carry a genetic marker called the "Mu phase" which turns their blood blue and causes some memory loss when they mature.

The story reveals that two Mu floating cities appeared above Tokyo and Sendai around the end of 2012. The ensuing conflict between Mu and humans escalated into nuclear warfare, and the Mu enveloped Tokyo and the outlying suburbs within a spherical barrier resembling Jupiter, referred by outsiders as "Tokyo Jupiter" ("Tōkyō Jupita"). The barrier has a time dilating effect, which causes time inside Tokyo Jupiter to slow down to one-fifth compared to the outside time, and allowed the Mu to secretly take control of Tokyo, using the area as their base of operations. The goal of the human forces outside of Tokyo Jupiter is to build up their strength to penetrate through and invade Tokyo Jupiter and stop the Mu while surviving their attacks.

Although RahXephon is part of the mecha genre of anime, its "mechas" are not mechanical. The mechas, used by the Mu and called Dolems, are made out of clay, like golems. Each is bound to a certain Mulian; however, some are also bound to certain human hosts, called "sub-Mulians".

The dominant theme of RahXephon is the music changing the world. The Dolems are animated by a mystical force connected to music; most of the controlling Mulians appear to be singing. A Dolem attacks while singing, and sometimes the attack is the song itself. The RahXephon can also attack by having its pilot—the "instrumentalist"—sing a note. This unleashes force waves that cause massive destruction. Each Mulian Dolem has an Italian name referring to musical notations, such as, Allegretto, Falsetto, or Vivace. The ultimate goal of the RahXephon is to "tune the world." Izubuchi says the name RahXephon lacked a real meaning, but that he now explains it as composed of Rah as the origin of Ra according to Churchward, X as the unknown variable or X factor, and -ephon as a suffix for instrument from "-phone".[3]

Plot[edit]

The most important plot line of the series is the unusual relationship between Ayato Kamina and Haruka Shitow. Although Haruka appears to be a stranger to Ayato at first, the series reveals that they knew each other from before the beginning of the story.

Ayato is a boy who was unknowingly conceived with the help of the Bähbem Foundation living in Tokyo with his adoptive mother, Maya Kamina. Ayato had met Haruka on a trip outside of Tokyo, and they continued to see each other when they returned to school in Tokyo. At this time, Haruka's family name was Mishima.

However, during what later became known as the Tokyo Jupiter incident, Haruka and her pregnant mother were away on a holiday trip while Ayato was caught inside the city. Years later, after giving birth to Haruka's sister Megumi, Haruka's mother remarried and their family name became Shitow. Meanwhile, Maya modified Ayato's memories to make him forget Haruka. The series makes clear that all of the humans within Tokyo Jupiter are subject to the same kind of mental control, thinking that they are all that's left of mankind after a devastating war. Ayato is haunted by visions of Haruka, which he manifests in his art. Ixtli, RahXephon's soul, also adopts Haruka's appearance and family name (Mishima) to guide Ayato, but takes a different given name—Reika.

The story begins as Tokyo comes under attack by invading aircraft while a mysterious woman, later revealed to be Haruka, stalks Ayato. By this point, Haruka has grown considerably older than Ayato and everyone else who is inside of Tokyo Jupiter because of the time dilation. Because of this and her now having a different last name, Ayato does not recognize Haruka and also initially does not fully trust her, but he gradually re-discovers his love for her as the series progresses, and he learns of everything that has happened. At the end of the series, Ayato's RahXephon merges with Quon's, allowing him to modify the past by "re-tuning the world" to make it so that he and Haruka are never separated. In the final sequence of the series, the adult Ayato is seen with his wife Haruka and their infant daughter Quon.

Characters[edit]

- This section represents the story from the television series and may differ from other works.

At the beginning of RahXephon, Ayato Kamina is a modest 17-year-old living in Tokyo. He is an average student, who enjoys painting and spending time with his classmates Hiroko Asahina and Mamoru Torigai. He has affectionate relationship with his mother, strained by her long-hour work.

During the sudden attack on Tokyo, Ayato hears the singing of his classmate Reika Mishima. She leads him to a giant egg containing the RahXephon. Haruka Shitow, an agent of the defense research agency TERRA (acronym for Tereno Empireo Rapidmova Reakcii Armeo, broken Esperanto for Earth Empire Rapid Response Army), brings Ayato and the RahXephon to their headquarters.

Ayato moves in with Haruka's uncle Professor Rikudoh and pilots the RahXephon against the attacking Dolems. Quon Kisaragi, a mysterious girl living with chief researcher Itsuki, seems to share some of Ayato's artistic talent. Ernst von Bähbem of the Bähbem Foundation sponsors TERRA through the Federation, the successor of the United Nations.

While most characters are introduced by the end of episode 7, RahXephon continues to characters development and reveals their mysteries and relationships through heavy use of foreshadowing.

Dolems[edit]

Dolems, or Dorems (ドーレム, Doremu), are enormous mecha-like beings that are used as powerful weapons by the Mulians. The name "Dolem" is derived from "golem".[4] It is also a reference to the first three notes in the C major scale, "Do-Re-Mi", and the Italian word "dolere", meaning "to ache".

In RahXephon Dolems are designated by TERRA as D1. The smaller fighters Dotem (with T instead of L) are designated as D2.

Dolems are made of clay, like golems, but are animated by a quasi-mystical force connected to music, as most of the controlling Mulians appear to be singing. A Dolem attacks while singing, and sometimes the attack is the song itself. Each D1 Dolem is bound to a Mulian who controls it. Some Dolems are also bound to human hosts called "sub-Mulians" or "Dolem hosts" who anchor to the Dolems in the human dimension, making it possible for the Mulian controller to take over the body of the host. These bonds are so strong that destroying a Dolem can kill both the Mulian controlling it and the human host. When destroyed, a Dolem disintegrates into blue blood and clay.

List of Dolems[edit]

- Allegretto

- Fortissimo

- Grave

- Ritardando

- Forzando

- Sforzando

- Larghetto

- Vivace

- Falsetto

- Arpeggio

- Alternate

- Vibrato

- Obbligato and Brillante

- Largo

Lesser Dolems[edit]

- Metronomes and Metronomilies

- Dotems

- Mezzofortes

- Staccato

Production and media[edit]

RahXephon was initially produced as a TV series. A manga version, novels, soundtracks and an audio drama were published during the original broadcast. A movie, an OVA episode, art books, and guide books were also created. Characters, mecha and story from RahXephon were featured in three video games.

TV series[edit]

Yutaka Izubuchi was a successful anime supervisor and designer focusing on costume, character and mechanical design, notably in the Gundam and Patlabor series. His friend and former Sunrise colleague Masahiko Minami, producer and president of Bones, had suggested Izubuchi to direct something.[5]

Izubuchi finally agreed and RahXephon became his first directing job. Izubuchi returned to the classic mecha shows of the 1970s and 1980s and wanted to make a show of that type updated with advances in anime production as well as adding his own personal ideas. He wanted to "set a new standard in the field" of mecha anime[5] to show his "own standard" and capabilities as a creator-showrunner.[6] Media Factory, Fuji TV. and Victor Entertainment joined Bones as production partners. After planning the story and designing characters and locations, a core group was expanded to a full production staff that completed the show, primarily working together — a departure from the trend of outsourcing anime production.[7]