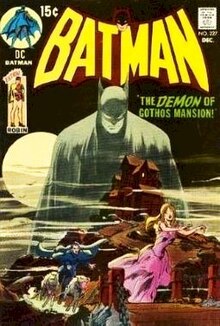

Batman theme by shagg_187

Download: Batman.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

It has been suggested that Batman (Jace Fox) be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since June 2024. |

| Batman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Publication information | |

| Publisher | DC Comics |

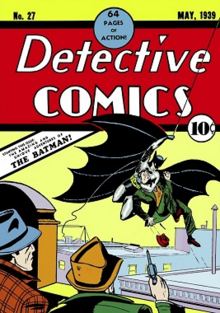

| First appearance | Detective Comics #27 (cover-dated May 1939; published March 30, 1939)[1] |

| Created by | |

| In-story information | |

| Alter ego | Bruce Wayne |

| Place of origin | Gotham City |

| Team affiliations | |

| Partnerships |

|

| Notable aliases |

|

| Abilities |

|

Batman[a] is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. The character was created by artist Bob Kane and writer Bill Finger, and debuted in the 27th issue of the comic book Detective Comics on March 30, 1939. In the DC Universe continuity, Batman is the alias of Bruce Wayne, a wealthy American playboy, philanthropist, and industrialist who resides in Gotham City. Batman's origin story features him swearing vengeance against criminals after witnessing the murder of his parents Thomas and Martha as a child, a vendetta tempered with the ideal of justice. He trains himself physically and intellectually, crafts a bat-inspired persona, and monitors the Gotham streets at night. Kane, Finger, and other creators accompanied Batman with supporting characters, including his sidekicks Robin and Batgirl; allies Alfred Pennyworth, James Gordon, and love interest Catwoman; and foes such as the Penguin, the Riddler, Two-Face, and his archenemy, the Joker.

DC has featured Batman in many comic books, including comics published under its imprints such as Vertigo and Black Label. The longest-running Batman comic, Detective Comics, is the longest-running comic book in the United States. Batman is frequently depicted alongside other DC superheroes, such as Superman and Wonder Woman, as a member of organizations such as the Justice League and the Outsiders. In addition to Bruce Wayne, other characters have taken on the Batman persona on different occasions, such as Jean-Paul Valley / Azrael in the 1993–1994 "Knightfall" story arc; Dick Grayson, the first Robin, from 2009 to 2011; and Jace Fox, son of Wayne's ally Lucius, as of 2021.[4] DC has also published comics featuring alternate versions of Batman, including the incarnation seen in The Dark Knight Returns and its successors, the incarnation from the Flashpoint (2011) event, and numerous interpretations from Elseworlds stories.

One of the most iconic characters in popular culture, Batman has been listed among the greatest comic book superheroes and fictional characters ever created. He is one of the most commercially successful superheroes, and his likeness has been licensed and featured in various media and merchandise sold around the world; this includes toy lines such as Lego Batman and video games like the Batman: Arkham series. Batman has been adapted in live-action and animated incarnations, including the 1960s Batman television series played by Adam West and in film by Michael Keaton in Batman (1989), Batman Returns (1992), and The Flash (2023), Val Kilmer in Batman Forever (1995), George Clooney in Batman & Robin (1997), Christian Bale in The Dark Knight trilogy (2005–2012), Ben Affleck in the DC Extended Universe (2016–2023), and Robert Pattinson in The Batman (2022). Many actors, most prolifically Kevin Conroy, have provided the character's voice in animation and video games.

Publication history[edit]

Creation[edit]

In early 1939, the success of Superman in Action Comics prompted editors at National Comics Publications (the future DC Comics) to request more superheroes for its titles. In response, Bob Kane created "the Bat-Man".[6] Collaborator Bill Finger recalled that "Kane had an idea for a character called 'Batman,' and he'd like me to see the drawings. I went over to Kane's, and he had drawn a character who looked very much like Superman with kind of ...reddish tights, I believe, with boots ...no gloves, no gauntlets ...with a small domino mask, swinging on a rope. He had two stiff wings that were sticking out, looking like bat wings. And under it was a big sign ...BATMAN".[7] According to Kane, the bat-wing-like cape was inspired by his childhood recollection of Leonardo da Vinci's sketch of an ornithopter flying device.[8]

Finger suggested giving the character a cowl instead of a simple domino mask, a cape instead of wings, and gloves; he also recommended removing the red sections from the original costume.[9][10][11][12] Finger said he devised the name Bruce Wayne for the character's secret identity: "Bruce Wayne's first name came from Robert the Bruce, the Scottish patriot. Wayne, being a playboy, was a man of gentry. I searched for a name that would suggest colonialism. I tried Adams, Hancock ...then I thought of Mad Anthony Wayne."[13] He later said his suggestions were influenced by Lee Falk's popular The Phantom, a syndicated newspaper comic-strip character with which Kane was also familiar.[14]

Kane and Finger drew upon contemporary 1930s popular culture for inspiration regarding much of the Bat-Man's look, personality, methods, and weaponry. Details find predecessors in pulp fiction, comic strips, newspaper headlines, and autobiographical details referring to Kane himself.[15] As an aristocratic hero with a double identity, Batman has predecessors in the Scarlet Pimpernel (created by Baroness Emmuska Orczy, 1903) and Zorro (created by Johnston McCulley, 1919). Like them, Batman performs his heroic deeds in secret, averts suspicion by playing aloof in public, and marks his work with a signature symbol. Kane noted the influence of the films The Mark of Zorro (1920) and The Bat Whispers (1930) in the creation of the character's iconography. Finger, drawing inspiration from pulp heroes like Doc Savage, The Shadow, Dick Tracy, and Sherlock Holmes, made the character a master sleuth.[16][17]

In his 1989 autobiography, Kane detailed Finger's contributions to Batman's creation:

One day I called Bill and said, 'I have a new character called the Bat-Man and I've made some crude, elementary sketches I'd like you to look at.' He came over and I showed him the drawings. At the time, I only had a small domino mask, like the one Robin later wore, on Batman's face. Bill said, 'Why not make him look more like a bat and put a hood on him, and take the eyeballs out and just put slits for eyes to make him look more mysterious?' At this point, the Bat-Man wore a red union suit; the wings, trunks, and mask were black. I thought that red and black would be a good combination. Bill said that the costume was too bright: 'Color it dark grey to make it look more ominous.' The cape looked like two stiff bat wings attached to his arms. As Bill and I talked, we realized that these wings would get cumbersome when Bat-Man was in action and changed them into a cape, scalloped to look like bat wings when he was fighting or swinging down on a rope. Also, he didn't have any gloves on, and we added them so that he wouldn't leave fingerprints.[14]

Subsequent creation credit[edit]

Kane signed away ownership in the character in exchange for, among other compensation, a mandatory byline on all Batman comics. This byline did not originally say "Batman created by Bob Kane"; his name was simply written on the title page of each story. The name disappeared from the comic book in the mid-1960s, replaced by credits for each story's actual writer and artists. In the late 1970s, when Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster began receiving a "created by" credit on the Superman titles, along with William Moulton Marston being given the byline for creating Wonder Woman, Batman stories began saying "Created by Bob Kane" in addition to the other credits.

Finger did not receive the same recognition. While he had received credit for other DC work since the 1940s, he began, in the 1960s, to receive limited acknowledgment for his Batman writing; in the letters page of Batman #169 (February 1965) for example, editor Julius Schwartz names him as the creator of the Riddler, one of Batman's recurring villains. However, Finger's contract left him only with his writing page rate and no byline. Kane wrote, "Bill was disheartened by the lack of major accomplishments in his career. He felt that he had not used his creative potential to its fullest and that success had passed him by."[13] At the time of Finger's death in 1974, DC had not officially credited Finger as Batman co-creator.

Jerry Robinson, who also worked with Finger and Kane on the strip at this time, has criticized Kane for failing to share the credit. He recalled Finger resenting his position, stating in a 2005 interview with The Comics Journal:

Bob made him more insecure, because while he slaved working on Batman, he wasn't sharing in any of the glory or the money that Bob began to make, which is why ...[he was] going to leave [Kane's employ]. ...[Kane] should have credited Bill as co-creator, because I know; I was there. ...That was one thing I would never forgive Bob for, was not to take care of Bill or recognize his vital role in the creation of Batman. As with Siegel and Shuster, it should have been the same, the same co-creator credit in the strip, writer, and artist.[18]

Although Kane initially rebutted Finger's claims at having created the character, writing in a 1965 open letter to fans that "it seemed to me that Bill Finger has given out the impression that he and not myself created the ''Batman, t' [sic] as well as Robin and all the other leading villains and characters. This statement is fraudulent and entirely untrue." Kane himself also commented on Finger's lack of credit. "The trouble with being a 'ghost' writer or artist is that you must remain rather anonymously without 'credit'. However, if one wants the 'credit', then one has to cease being a 'ghost' or follower and become a leader or innovator."[19]

In 1989, Kane revisited Finger's situation, recalling in an interview:

In those days it was like, one artist and he had his name over it [the comic strip] — the policy of DC in the comic books was, if you can't write it, obtain other writers, but their names would never appear on the comic book in the finished version. So Bill never asked me for it [the byline] and I never volunteered — I guess my ego at that time. And I felt badly, really, when he [Finger] died.[20]

In September 2015, DC Entertainment revealed that Finger would be receiving credit for his role in Batman's creation on the 2016 superhero film Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice and the second season of Gotham after a deal was worked out between the Finger family and DC.[2] Finger received credit as a creator of Batman for the first time in a comic in October 2015 with Batman and Robin Eternal #3 and Batman: Arkham Knight Genesis #3. The updated acknowledgment for the character appeared as "Batman created by Bob Kane with Bill Finger".[3]

Golden Age[edit]

Early years[edit]

The first Batman story, "The Case of the Chemical Syndicate", was published in Detective Comics #27 (cover dated May 1939). It largely duplicated the plot of the story "Partners of Peril" in The Shadow #113, which was written by Theodore Tinsley and illustrated by Tom Lovell.[21] Finger said, "Batman was originally written in the style of the pulps",[22] and this influence was evident with Batman showing little remorse over killing or maiming criminals. Batman proved a hit character, and he received his own solo title in 1940 while continuing to star in Detective Comics. By that time, Detective Comics was the top-selling and most influential publisher in the industry; Batman and the company's other major hero, Superman, were the cornerstones of the company's success.[23] The two characters were featured side by side as the stars of World's Finest Comics, which was originally titled World's Best Comics when it debuted in fall 1940. Creators including Jerry Robinson and Dick Sprang also worked on the strips during this period.

Over the course of the first few Batman strips elements were added to the character and the artistic depiction of Batman evolved. Kane noted that within six issues he drew the character's jawline more pronounced, and lengthened the ears on the costume. "About a year later he was almost the full figure, my mature Batman", Kane said.[24] Batman's characteristic utility belt was introduced in Detective Comics #29 (July 1939), followed by the boomerang-like batarang and the first bat-themed vehicle, the Batplane, in #31 (September 1939). The character's origin was revealed in #33 (November 1939), unfolding in a two-page story that establishes the brooding persona of Batman, a character driven by the death of his parents. Written by Finger, it depicts a young Bruce Wayne witnessing his parents' murder at the hands of a mugger. Days later, at their grave, the child vows that "by the spirits of my parents [I will] avenge their deaths by spending the rest of my life warring on all criminals".[25][26][27]

The early, pulp-inflected portrayal of Batman started to soften in Detective Comics #38 (April 1940) with the introduction of Robin, Batman's junior counterpart.[28] Robin was introduced, based on Finger's suggestion, because Batman needed a "Watson" with whom Batman could talk.[29] Sales nearly doubled, despite Kane's preference for a solo Batman, and it sparked a proliferation of "kid sidekicks".[30] The first issue of the solo spin-off series Batman was notable not only for introducing two of his most persistent enemies, the Joker and Catwoman, but for a pre-Robin inventory story, originally meant for Detective Comics #38, in which Batman shoots some monstrous giants to death.[31][32] That story prompted editor Whitney Ellsworth to decree that the character could no longer kill or use a gun.[33]

By 1942, the writers and artists behind the Batman comics had established most of the basic elements of the Batman mythos.[34] In the years following World War II, DC Comics "adopted a postwar editorial direction that increasingly de-emphasized social commentary in favor of lighthearted juvenile fantasy". The impact of this editorial approach was evident in Batman comics of the postwar period; removed from the "bleak and menacing world" of the strips of the early 1940s, Batman was instead portrayed as a respectable citizen and paternal figure that inhabited a "bright and colorful" environment.[35]

Silver and Bronze Ages[edit]

1950s and early 1960s[edit]

Batman was one of the few superhero characters to be continuously published as interest in the genre waned during the 1950s. In the story "The Mightiest Team in the World" in Superman #76 (June 1952), Batman teams up with Superman for the first time and the pair discover each other's secret identity.[36] Following the success of this story, World's Finest Comics was revamped so it featured stories starring both heroes together, instead of the separate Batman and Superman features that had been running before.[37] The team-up of the characters was "a financial success in an era when those were few and far between";[38] this series of stories ran until the book's cancellation in 1986.

Batman comics were among those criticized when the comic book industry came under scrutiny with the publication of psychologist Fredric Wertham's book Seduction of the Innocent in 1954. Wertham's thesis was that children imitated crimes committed in comic books, and that these works corrupted the morals of the youth. Wertham criticized Batman comics for their supposed homosexual overtones and argued that Batman and Robin were portrayed as lovers.[39] Wertham's criticisms raised a public outcry during the 1950s, eventually leading to the establishment of the Comics Code Authority, a code that is no longer in use by the comic book industry. The tendency towards a "sunnier Batman" in the postwar years intensified after the introduction of the Comics Code.[40] Scholars have suggested that the characters of Batwoman (in 1956) and the pre-Barbara Gordon Bat-Girl (in 1961) were introduced in part to refute the allegation that Batman and Robin were gay, and the stories took on a campier, lighter feel.[41]

In the late 1950s, Batman stories gradually became more science fiction-oriented, an attempt at mimicking the success of other DC characters that had dabbled in the genre.[42] New characters such as Batwoman, the original Bat-Girl, Ace the Bat-Hound, and Bat-Mite were introduced. Batman's adventures often involved odd transformations or bizarre space aliens. In 1960, Batman debuted as a member of the Justice League of America in The Brave and the Bold #28 (February 1960), and went on to appear in several Justice League comic book series starting later that same year.

"New Look" Batman and camp[edit]

By 1964, sales of Batman titles had fallen drastically. Bob Kane noted that, as a result, DC was "planning to kill Batman off altogether".[43] In response to this, editor Julius Schwartz was assigned to the Batman titles. He presided over drastic changes, beginning with 1964's Detective Comics #327 (May 1964), which was cover-billed as the "New Look". Schwartz introduced changes designed to make Batman more contemporary, and to return him to more detective-oriented stories. He brought in artist Carmine Infantino to help overhaul the character. The Batmobile was redesigned, and Batman's costume was modified to incorporate a yellow ellipse behind the bat-insignia. The space aliens, time travel, and characters of the 1950s such as Batwoman, Ace the Bat-Hound, and Bat-Mite were retired. Bruce Wayne's butler Alfred was killed off (though his death was quickly reversed) while a new female relative for the Wayne family, Aunt Harriet Cooper, came to live with Bruce Wayne and Dick Grayson.[44]

The debut of the Batman television series in 1966 had a profound influence on the character. The success of the series increased sales throughout the comic book industry, and Batman reached a circulation of close to 900,000 copies.[45] Elements such as the character of Batgirl and the show's campy nature were introduced into the comics; the series also initiated the return of Alfred. Although both the comics and TV show were successful for a time, the camp approach eventually wore thin and the show was canceled in 1968. In the aftermath, the Batman comics themselves lost popularity once again. As Julius Schwartz noted, "When the television show was a success, I was asked to be campy, and of course when the show faded, so did the comic books."[46]

Starting in 1969, writer Dennis O'Neil and artist Neal Adams made a deliberate effort to distance Batman from the campy portrayal of the 1960s TV series and to return the character to his roots as a "grim avenger of the night".[47] O'Neil said his idea was "simply to take it back to where it started. I went to the DC library and read some of the early stories. I tried to get a sense of what Kane and Finger were after."[48]

O'Neil and Adams first collaborated on the story "The Secret of the Waiting Graves" in Detective Comics #395 (January 1970). Few stories were true collaborations between O'Neil, Adams, Schwartz, and inker Dick Giordano, and in actuality these men were mixed and matched with various other creators during the 1970s; nevertheless the influence of their work was "tremendous".[49] Giordano said: "We went back to a grimmer, darker Batman, and I think that's why these stories did so well ..."[50] While the work of O'Neil and Adams was popular with fans, the acclaim did little to improve declining sales; the same held true with a similarly acclaimed run by writer Steve Englehart and penciler Marshall Rogers in Detective Comics #471–476 (August 1977 – April 1978), which went on to influence the 1989 movie Batman and be adapted for Batman: The Animated Series, which debuted in 1992.[51] Regardless, circulation continued to drop through the 1970s and 1980s, hitting an all-time low in 1985.[52]

Modern Age[edit]

The Dark Knight Returns[edit]

Frank Miller's limited series The Dark Knight Returns (February–June 1986) returned the character to his darker roots, both in atmosphere and tone. The comic book, which tells the story of a 55-year-old Batman coming out of retirement in a possible future, reinvigorated interest in the character. The Dark Knight Returns was a financial success and has since become one of the medium's most noted touchstones.[53] The series also sparked a major resurgence in the character's popularity.[54]

That year Dennis O'Neil took over as editor of the Batman titles and set the template for the portrayal of Batman following DC's status quo-altering 12-issue miniseries Crisis on Infinite Earths. O'Neil operated under the assumption that he was hired to revamp the character and as a result tried to instill a different tone in the books than had gone before.[55] One outcome of this new approach was the "Year One" storyline in Batman #404–407 (February–May 1987), in which Frank Miller and artist David Mazzucchelli redefined the character's origins.[56] Writer Alan Moore and artist Brian Bolland continued this dark trend with 1988's 48-page one-shot issue Batman: The Killing Joke, in which the Joker, attempting to drive Commissioner Gordon insane, cripples Gordon's daughter Barbara, and then kidnaps and tortures the commissioner, physically and psychologically.[57]

The Batman comics garnered major attention in 1988 when DC Comics created a 900 number for readers to call to vote on whether Jason Todd, the second Robin, lived or died. Voters decided in favor of Jason's death by a narrow margin of 28 votes (see Batman: A Death in the Family).[56]

Knightfall[edit]

The 1993 "Knightfall" story arc introduced a new villain, Bane, who critically injures Batman after pushing him to the limits of his endurance. Jean-Paul Valley, known as Azrael, is called upon to wear the Batsuit during Bruce Wayne's convalescence. Writers Doug Moench,

The Simpsons theme by borrer0 Download: TheSimpsons_2.p3t

The Simpsons is an American animated sitcom created by Matt Groening for the Fox Broadcasting Company.[1][2][3] Developed by Groening, James L. Brooks, and Sam Simon, the series is a satirical depiction of American life, epitomized by the Simpson family, which consists of Homer, Marge, Bart, Lisa, and Maggie. Set in the fictional town of Springfield, it caricatures society, Western culture, television, and the human condition.

The family was conceived by Groening shortly before a solicitation for a series of animated shorts with producer Brooks. He created a dysfunctional family and named the characters after his own family members, substituting Bart for his own name; he thought Simpson was a funny name in that it sounded similar to "simpleton".[4] The shorts became a part of The Tracey Ullman Show on April 19, 1987. After three seasons, the sketch was developed into a half-hour prime time show and became Fox's first series to land in the Top 30 ratings in a season (1989–1990).

Since its debut on December 17, 1989, 768 episodes of the show have been broadcast. It is the longest-running American animated series, longest-running American sitcom, and the longest-running American scripted primetime television series, both in seasons and individual episodes. A feature-length film, The Simpsons Movie, was released in theaters worldwide on July 27, 2007, to critical and commercial success, with a sequel in development as of 2018. The series has also spawned numerous comic book series, video games, books, and other related media, as well as a billion-dollar merchandising industry. The Simpsons is a joint production by Gracie Films and 20th Television.[5]

On January 26, 2023, the series was renewed for its 35th and 36th seasons, taking the show through the 2024–25 television season.[6] Both seasons contain a combined total of 51 episodes. Seven of these episodes are season 34 holdovers, while the other 44 will be produced in the production cycle of the upcoming seasons, bringing the show's overall episode total up to 801.[7] Season 35 premiered on October 1, 2023.[8]

The Simpsons received widespread acclaim throughout its early seasons in the 1990s, which are generally considered its "golden age". Since then, it has been criticized for a perceived decline in quality. Time named it the 20th century's best television series,[9] and Erik Adams of The A.V. Club named it "television's crowning achievement regardless of format".[10] On January 14, 2000, the Simpson family was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. It has won dozens of awards since it debuted as a series, including 37 Primetime Emmy Awards, 34 Annie Awards, and 2 Peabody Awards. Homer's exclamatory catchphrase of "D'oh!" has been adopted into the English language, while The Simpsons has influenced many other later adult-oriented animated sitcom television series.

The main characters are the Simpson family, who live in the fictional "Middle America" town of Springfield.[11] Homer, the father, works as a safety inspector at the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant, a position at odds with his careless, buffoonish personality. He is married to Marge (née Bouvier), a stereotypical American housewife and mother. They have three children: Bart, a ten-year-old troublemaker and prankster; Lisa, a precocious eight-year-old activist; and Maggie, the baby of the family who rarely speaks, but communicates by sucking on a pacifier. Although the family is dysfunctional, many episodes examine their relationships and bonds with each other and they are often shown to care about one another.[12]

The family also owns a greyhound, Santa's Little Helper, (who first appeared in the episode "Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire" and a cat, Snowball II, who is replaced by a cat also called Snowball II in the fifteenth-season episode "I, (Annoyed Grunt)-Bot".[13] Extended members of the Simpson and Bouvier family in the main cast include Homer's father Abe and Marge's sisters Patty and Selma. Marge's mother Jacqueline and Homer's mother Mona appear less frequently.

The show includes a vast array of quirky supporting characters, which include Homer's friends Barney Gumble, Lenny Leonard and Carl Carlson; the school principal Seymour Skinner and staff members such as Edna Krabappel and Groundskeeper Willie; students such as Milhouse Van Houten, Nelson Muntz and Ralph Wiggum; shopkeepers such as Apu Nahasapeemapetilon, Comic Book Guy and Moe Szyslak; government figures Mayor "Diamond" Joe Quimby and Clancy Wiggum; next-door neighbor Ned Flanders; local celebrities such as Krusty the Clown and news reporter Kent Brockman; nuclear tycoon Montgomery Burns and his devoted assistant Waylon Smithers; and dozens more.

The creators originally intended many of these characters as one-time jokes or for fulfilling needed functions in the town. A number of them have gained expanded roles and subsequently starred in their own episodes. According to Matt Groening, the show adopted the concept of a large supporting cast from the comedy show SCTV.[14]

Despite the depiction of yearly milestones such as holidays or birthdays passing, the characters never age. The series uses a floating timeline in which episodes generally take place in the year the episode is produced. Flashbacks and flashforwards do occasionally depict the characters at other points in their lives, with the timeline of these depictions also generally floating relative to the year the episode is produced. For example, the 1991 episodes "The Way We Was" and "I Married Marge" depict Homer and Marge as high schoolers in the 1970s who had Bart (who is always 10 years old) in the early '80s, while the 2008 episode "That '90s Show" depicts Homer and Marge as a childless couple in the '90s, and the 2021 episode "Do Pizza Bots Dream of Electric Guitars" portrays Homer as an adolescent in the same period. The 1995 episode "Lisa's Wedding" takes place during Lisa's college years in the then-future year of 2010, the same year the show began airing its 22nd season, in which Lisa was still 8. Regarding the contradictory flashbacks, Selman stated that "they all kind of happened in their imaginary world."[15]

The show follows a loose and inconsistent continuity. For example, Krusty the Clown may be able to read in one episode, but not in another. However, it is consistently portrayed that he is Jewish, that his father was a rabbi, and that his career began in the 1960s. The latter point introduces another snag in the floating timeline: historical periods that are a core part of a character's backstory remain so even when their age makes it unlikely or impossible, such as Grampa Simpson and Principal Skinner's respective service in World War II and Vietnam.

The only episodes not part of the series' main canon are the Treehouse of Horror episodes, which often feature the deaths of main characters. Characters who die in "regular" episodes, such as Maude Flanders, Mona Simpson and Edna Krabappel, however, stay dead. Most episodes end with the status quo being restored, though occasionally major changes will stick, such as Lisa's conversions to vegetarianism and Buddhism, the divorce of Milhouse van Houten's parents, and the marriage and subsequent parenthood of Apu and Manjula.

The Simpsons takes place in a fictional American town called Springfield. Although there are many real settlements in America named Springfield,[16] the town the show is set in is fictional. The state it is in is not established. In fact, the show is intentionally evasive with regard to Springfield's location.[17] Springfield's geography and that of its surroundings is inconsistent: from one episode to another, it may have coastlines, deserts, vast farmland, mountains, or whatever the story or joke requires.[18] Groening has said that Springfield has much in common with Portland, Oregon, the city where he grew up.[19] Groening has said that he named it after Springfield, Oregon, and the fictitious Springfield which was the setting of the series Father Knows Best. He "figured out that Springfield was one of the most common names for a city in the U.S. In anticipation of the success of the show, I thought, 'This will be cool; everyone will think it's their Springfield.' And they do."[20] Many landmarks, including street names, have connections to Portland.[21]

When producer James L. Brooks was working on the television variety show The Tracey Ullman Show, he decided to include small animated sketches before and after the commercial breaks. Having seen one of cartoonist Matt Groening's Life in Hell comic strips, Brooks asked Groening to pitch an idea for a series of animated shorts. Groening initially intended to present an animated version of his Life in Hell series.[22] However, Groening later realized that animating Life in Hell would require the rescinding of publication rights for his life's work. He therefore chose another approach while waiting in the lobby of Brooks's office for the pitch meeting, hurriedly formulating his version of a dysfunctional family that became the Simpsons.[22][23] He named the characters after his own family members, substituting "Bart" for his own name, adopting an anagram of the word brat.[22]

The Simpson family first appeared as shorts in The Tracey Ullman Show on April 19, 1987.[24] Groening submitted only basic sketches to the animators and assumed that the figures would be cleaned up in production. However, the animators merely re-traced his drawings, which led to the crude appearance of the characters in the initial shorts.[22] The animation was produced domestically at Klasky Csupo,[25][26] with Wes Archer, David Silverman, and Bill Kopp being animators for the first season.[27] The colorist, "Georgie" Gyorgyi Kovacs Peluce (Kovács Györgyike)[28][29][30][31][32][33] made the characters yellow; as Bart, Lisa and Maggie have no hairlines, she felt they would look strange if they were flesh-colored. Groening supported the decision, saying: "Marge is yellow with blue hair? That's hilarious — let's do it!"[27]

In 1989, a team of production companies adapted The Simpsons into a half-hour series for the Fox Broadcasting Company. The team included the Klasky Csupo animation house. Brooks negotiated a provision in the contract with the Fox network that prevented Fox from interfering with the show's content.[34] Groening said his goal in creating the show was to offer the audience an alternative to what he called "the mainstream trash" that they were watching.[35] The half-hour series premiered on December 17, 1989, with "Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire".[36] "Some Enchanted Evening" was the first full-length episode produced, but it did not broadcast until May 1990, as the last episode of the first season, because of animation problems.[37] In 1992, Tracey Ullman filed a lawsuit against Fox, claiming that her show was the source of the series' success. The suit said she should receive a share of the profits of The Simpsons[38]—a claim rejected by the courts.[39]

List of showrunners throughout the series' run:

Matt Groening and James L. Brooks have served as executive producers during the show's entire history, and also function as creative consultants. Sam Simon, described by former Simpsons director Brad Bird as "the unsung hero" of the show,[40] served as creative supervisor for the first four seasons. He was constantly at odds with Groening, Brooks and the show's production company Gracie Films and left in 1993.[41] Before leaving, he negotiated a deal that sees him receive a share of the profits every year, and an executive producer credit despite not having worked on the show since 1993,[41][42] at least until his passing in 2015.[43] A more involved position on the show is the showrunner, who acts as head writer and manages the show's production for an entire season.[27]

The first team of writers, assembled by Sam Simon, consisted of John Swartzwelder, Jon Vitti, George Meyer, Jeff Martin, Al Jean, Mike Reiss, Jay Kogen and Wallace Wolodarsky.[44] Newer Simpsons' writing teams typically consist of sixteen writers who propose episode ideas at the beginning of each December.[45] The main writer of each episode writes the first draft. Group rewriting sessions develop final scripts by adding or removing jokes, inserting scenes, and calling for re-readings of lines by the show's vocal performers.[46] Until 2004,[47] George Meyer, who had developed the show since the first season, was active in these sessions. According to long-time writer Jon Vitti, Meyer usually invented the best lines in a given episode, even though other writers may receive script credits.[46] Each episode takes six months to produce so the show rarely comments on current events.[48]

Credited with sixty episodes, John Swartzwelder is the most prolific writer on The Simpsons.[49] One of the best-known former writers is Conan O'Brien, who contributed to several episodes in the early 1990s before replacing David Letterman as host of the talk show Late Night.[50] English comedian Ricky Gervais wrote the episode "Homer Simpson, This Is Your Wife", becoming the first celebrity both to write and guest star in the same episode.[51] Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg, writers of the film Superbad, wrote the episode "Homer the Whopper", with Rogen voicing a character in it.[52]

At the end of 2007, the writers of The Simpsons went on strike together with the other members of the Writers Guild of America, East. The show's writers had joined the guild in 1998.[53]

In May 2023, the writers of The Simpsons went on strike together with the other members of the Writers Guild of America, East.[54][55]

The Simpsons #2

(13 backgrounds)

The Simpsons

Genre Created by Matt Groening Based on The Simpsons shorts

by Matt GroeningDeveloped by Showrunners Voices of Theme music composer Danny Elfman Opening theme "The Simpsons Theme" Ending theme "The Simpsons Theme" (reprise) Composers Richard Gibbs (1989–1990)

Alf Clausen (1990–2017)

Bleeding Fingers Music (2017–present)Country of origin United States Original language English No. of seasons 35 No. of episodes 768 (list of episodes) Production Executive producers Producers Editors Running time 21–24 minutes Production companies Original release Network Fox Release December 17, 1989 –

presentPremise[edit]

Characters[edit]

Continuity and the floating timeline[edit]

Setting[edit]

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

Executive producers and showrunners[edit]

Writing[edit]

Voice actors[edit]