Beowulf theme by GunsOfLiberty

Download: Beowulf.p3t

(4 backgrounds)

| Beowulf | |

|---|---|

| Bēowulf | |

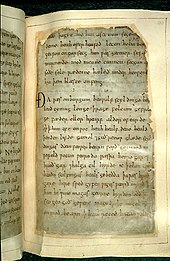

First page of Beowulf in Cotton Vitellius A. xv. Beginning: HWÆT. WE GARDE / na in geardagum, þeodcyninga / þrym gefrunon... (Translation: How much we of Spear-Da/nes, in days gone by, of kings / the glory have heard...) | |

| Author(s) | Unknown |

| Language | West Saxon dialect of Old English |

| Date | Disputed (c. 700–1000 AD) |

| State of existence | Manuscript suffered damage from fire in 1731 |

| Manuscript(s) | Cotton Vitellius A. xv (c. 975–1025 AD) |

| First printed edition | Thorkelin (1815) |

| Genre | Epic heroic writing |

| Verse form | Alliterative verse |

| Length | c. 3182 lines |

| Subject | The battles of Beowulf, the Geatish hero, in youth and old age |

| Personages | Beowulf, Hygelac, Hrothgar, Wealhtheow, Hrothulf, Æschere, Unferth, Grendel, Grendel's mother, Wiglaf, Hildeburh. Full list of characters. |

| Text | Beowulf at Wikisource |

Beowulf (/ˈbeɪəwʊlf/;[1] Old English: Bēowulf [ˈbeːowuɫf]) is an Old English epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature. The date of composition is a matter of contention among scholars; the only certain dating is for the manuscript, which was produced between 975 and 1025 AD.[2] Scholars call the anonymous author the "Beowulf poet".[3] The story is set in pagan Scandinavia in the 5th and 6th centuries. Beowulf, a hero of the Geats, comes to the aid of Hrothgar, the king of the Danes, whose mead hall Heorot has been under attack by the monster Grendel for twelve years. After Beowulf slays him, Grendel's mother takes revenge and is in turn defeated. Victorious, Beowulf goes home to Geatland and becomes king of the Geats. Fifty years later, Beowulf defeats a dragon, but is mortally wounded in the battle. After his death, his attendants cremate his body and erect a barrow on a headland in his memory.

Scholars have debated whether Beowulf was transmitted orally, affecting its interpretation: if it was composed early, in pagan times, then the paganism is central and the Christian elements were added later, whereas if it was composed later, in writing, by a Christian, then the pagan elements could be decorative archaising; some scholars also hold an intermediate position. Beowulf is written mostly in the Late West Saxon dialect of Old English, but many other dialectal forms are present, suggesting that the poem may have had a long and complex transmission throughout the dialect areas of England.

There has long been research into similarities with other traditions and accounts, including the Icelandic Grettis saga, the Norse story of Hrolf Kraki and his bear-shapeshifting servant Bodvar Bjarki, the international folktale the Bear's Son Tale, and the Irish folktale of the Hand and the Child. Persistent attempts have been made to link Beowulf to tales from Homer's Odyssey or Virgil's Aeneid. More definite are biblical parallels, with clear allusions to the books of Genesis, Exodus, and Daniel.

The poem survives in a single copy in the manuscript known as the Nowell Codex. It has no title in the original manuscript, but has become known by the name of the story's protagonist.[3] In 1731, the manuscript was damaged by a fire that swept through Ashburnham House in London, which was housing Sir Robert Cotton's collection of medieval manuscripts. It survived, but the margins were charred, and some readings were lost.[4] The Nowell Codex is housed in the British Library. The poem was first transcribed in 1786; some verses were first translated into modern English in 1805, and nine complete translations were made in the 19th century, including those by John Mitchell Kemble and William Morris. After 1900, hundreds of translations, whether into prose, rhyming verse, or alliterative verse were made, some relatively faithful, some archaising, some attempting to domesticate the work. Among the best-known modern translations are those of Edwin Morgan, Burton Raffel, Michael J. Alexander, Roy Liuzza, and Seamus Heaney. The difficulty of translating Beowulf has been explored by scholars including J. R. R. Tolkien (in his essay "On Translating Beowulf"), who worked on a verse and a prose translation of his own.

Historical background[edit]

The events in the poem take place over the 5th and 6th centuries, and feature predominantly non-English characters. Some suggest that Beowulf was first composed in the 7th century at Rendlesham in East Anglia, as the Sutton Hoo ship-burial shows close connections with Scandinavia, and the East Anglian royal dynasty, the Wuffingas, may have been descendants of the Geatish Wulfings.[6][5] Others have associated this poem with the court of King Alfred the Great or with the court of King Cnut the Great.[7]

The poem blends fictional, legendary, mythic and historical elements. Although Beowulf himself is not mentioned in any other Old English manuscript,[8] many of the other figures named in Beowulf appear in Scandinavian sources.[9] This concerns not only individuals (e.g., Healfdene, Hroðgar, Halga, Hroðulf, Eadgils and Ohthere), but also clans (e.g., Scyldings, Scylfings and Wulfings) and certain events (e.g., the battle between Eadgils and Onela). The raid by King Hygelac into Frisia is mentioned by Gregory of Tours in his History of the Franks and can be dated to around 521.[10]

The majority view appears to be that figures such as King Hrothgar and the Scyldings in Beowulf are based on historical people from 6th-century Scandinavia. Like the Finnesburg Fragment and several shorter surviving poems, Beowulf has consequently been used as a source of information about Scandinavian figures such as Eadgils and Hygelac, and about continental Germanic figures such as Offa, king of the continental Angles.[11] However, the scholar Roy Liuzza argues that the poem is "frustratingly ambivalent", neither myth nor folktale, but is set "against a complex background of legendary history ... on a roughly recognizable map of Scandinavia", and comments that the Geats of the poem may correspond with the Gautar (of modern Götaland); or perhaps the legendary Getae.[12]

19th-century archaeological evidence may confirm elements of the Beowulf story. Eadgils was buried at Uppsala (Gamla Uppsala, Sweden) according to Snorri Sturluson. When the western mound (to the left in the photo) was excavated in 1874, the finds showed that a powerful man was buried in a large barrow, c. 575, on a bear skin with two dogs and rich grave offerings. The eastern mound was excavated in 1854, and contained the remains of a woman, or a woman and a young man. The middle barrow has not been excavated.[14][13]

In Denmark, recent (1986-88, 2004-05)[15] archaeological excavations at Lejre, where Scandinavian tradition located the seat of the Scyldings, Heorot, have revealed that a hall was built in the mid-6th century, matching the period described in Beowulf, some centuries before the poem was composed.[16] Three halls, each about 50 metres (160 ft) long, were found during the excavation.[16]

Summary[edit]

Key: (a) sections 1–2 (b) 3–7 (c) 8–12 (d) 13–18 (e) 19–23 (f) 24–26 (g) 27–31 (h) 32–33 (i) 34–38 (j) 39–43

The protagonist Beowulf, a hero of the Geats, comes to the aid of Hrothgar, king of the Danes, whose great hall, Heorot, is plagued by the monster Grendel. Beowulf kills Grendel with his bare hands, then kills Grendel's mother with a giant's sword that he found in her lair.

Later in his life, Beowulf becomes king of the Geats, and finds his realm terrorised by a dragon, some of whose treasure had been stolen from his hoard in a burial mound. He attacks the dragon with the help of his thegns or servants, but they do not succeed. Beowulf decides to follow the dragon to its lair at Earnanæs, but only his young Swedish relative Wiglaf, whose name means "remnant of valour",[a] dares to join him. Beowulf finally slays the dragon, but is mortally wounded in the struggle. He is cremated and a burial mound by the sea is erected in his honour.

Beowulf is considered an epic poem in that the main character is a hero who travels great distances to prove his strength at impossible odds against supernatural demons and beasts. The poem begins in medias res or simply, "in the middle of things", a characteristic of the epics of antiquity. Although the poem begins with Beowulf's arrival, Grendel's attacks have been ongoing. An elaborate history of characters and their lineages is spoken of, as well as their interactions with each other, debts owed and repaid, and deeds of valour. The warriors form a brotherhood linked by loyalty to their lord. The poem begins and ends with funerals: at the beginning of the poem for Scyld Scefing[20] and at the end for Beowulf.[21]

The poem is tightly structured. E. Carrigan shows the symmetry of its design in a model of its major components, with for instance the account of the killing of Grendel matching that of the killing of the dragon, the glory of the Danes matching the accounts of the Danish and Geatish courts.[17] Other analyses are possible as well; Gale Owen-Crocker, for instance, sees the poem as structured by the four funerals it describes.[22] For J. R. R. Tolkien, the primary division in the poem was between young and old Beowulf.[23]

First battle: Grendel[edit]

Beowulf begins with the story of Hrothgar, who constructed the great hall, Heorot, for himself and his warriors. In it, he, his wife Wealhtheow, and his warriors spend their time singing and celebrating. Grendel, a troll-like monster said to be descended from the biblical Cain, is pained by the sounds of joy.[24] Grendel attacks the hall and kills and devours many of Hrothgar's warriors while they sleep. Hrothgar and his people, helpless against Grendel, abandon Heorot.

Beowulf, a young warrior from Geatland, hears of Hrothgar's troubles and with his king's permission leaves his homeland to assist Hrothgar.[25]

Beowulf and his men spend the night in Heorot. Beowulf refuses to use any weapon because he holds himself to be Grendel's equal.[26] When Grendel enters the hall, Beowulf, who has been feigning sleep, leaps up to clench Grendel's hand.[27] Grendel and Beowulf battle each other violently.[28] Beowulf's retainers draw their swords and rush to his aid, but their blades cannot pierce Grendel's skin.[29] Finally, Beowulf tears Grendel's arm from his body at the shoulder and Grendel runs to his home in the marshes where he dies.[30] Beowulf displays "the whole of Grendel's shoulder and arm, his awesome grasp" for all to see at Heorot. This display would fuel Grendel's mother's anger in revenge.[31]

Second battle: Grendel's mother[edit]

The next night, after celebrating Grendel's defeat, Hrothgar and his men sleep in Heorot. Grendel's mother, angry that her son has been killed, sets out to get revenge. "Beowulf was elsewhere. Earlier, after the award of treasure, The Geat had been given another lodging"; his assistance would be absent in this battle.[32] Grendel's mother violently kills Æschere, who is Hrothgar's most loyal fighter, and escapes.

Hrothgar, Beowulf, and their men track Grendel's mother to her lair under a lake. Unferð, a warrior who had earlier challenged him, presents Beowulf with his sword Hrunting. After stipulating a number of conditions to Hrothgar in case of his death (including the taking in of his kinsmen and the inheritance by Unferth of Beowulf's estate), Beowulf jumps into the lake and, while harassed by water monsters, gets to the bottom, where he finds a cavern. Grendel's mother pulls him in, and she and Beowulf engage in fierce combat.

At first, Grendel's mother prevails, and Hrunting proves incapable of hurting her; she throws Beowulf to the ground and, sitting astride him, tries to kill him with a short sword, but Beowulf is saved by his armour. Beowulf spots another sword, hanging on the wall and apparently made for giants, and cuts her head off with it. Travelling further into Grendel's mother's lair, Beowulf discovers Grendel's corpse and severs his head with the sword. Its blade melts because of the monster's "hot blood", leaving only the hilt. Beowulf swims back up to the edge of the lake where his men wait. Carrying the hilt of the sword and Grendel's head, he presents them to Hrothgar upon his return to Heorot. Hrothgar gives Beowulf many gifts, including the sword Nægling, his family's heirloom. The events prompt a long reflection by the king, sometimes referred to as "Hrothgar's sermon", in which he urges Beowulf to be wary of pride and to reward his thegns.[33]

Final battle: The dragon[edit]

Beowulf returns home and eventually becomes king of his own people. One day, fifty years after Beowulf's battle with Grendel's mother, a slave steals a golden cup from the lair of a dragon at Earnanæs. When the dragon sees that the cup has been stolen, it leaves its cave in a rage, burning everything in sight. Beowulf and his warriors come to fight the dragon, but Beowulf tells his men that he will fight the dragon alone and that they should wait on the barrow. Beowulf descends to do battle with the dragon, but finds himself outmatched. His men, upon seeing this and fearing for their lives, retreat into the woods. One of his men, Wiglaf, however, in great distress at Beowulf's plight, comes to his aid. The two slay the dragon, but Beowulf is mortally wounded. After Beowulf dies, Wiglaf remains by his side, grief-stricken. When the rest of the men finally return, Wiglaf bitterly admonishes them, blaming their cowardice for Beowulf's death. Beowulf is ritually burned on a great pyre in Geatland while his people wail and mourn him, fearing that without him, the Geats are defenceless against attacks from surrounding tribes. Afterwards, a barrow, visible from the sea, is built in his memory.[34][35]

Digressions[edit]

The poem contains many apparent digressions from the main story. These were found troublesome by early Beowulf scholars such as Frederick Klaeber, who wrote that they "interrupt the story",[36] W. W. Lawrence, who stated that they "clog the action and distract attention from it",[36] and W. P. Ker who found some "irrelevant ... possibly ... interpolations".[36] More recent scholars from Adrien Bonjour onwards note that the digressions can all be explained as introductions or comparisons with elements of the main story;[37][38] for instance, Beowulf's swimming home across the sea from Frisia carrying thirty sets of armour[39] emphasises his heroic strength.[38] The digressions can be divided into four groups, namely the Scyld narrative at the start;[40] many descriptions of the Geats, including the Swedish–Geatish wars,[41] the "Lay of the Last Survivor"[42] in the style of another Old English poem, "The Wanderer", and Beowulf's dealings with the Geats such as his verbal contest with Unferth and his swimming duel with Breca,[43] and the tale of Sigemund and the dragon;[44] history and legend, including the fight at Finnsburg[45] and the tale of Freawaru and Ingeld;[46] and biblical tales such as the creation myth and Cain as ancestor of all monsters.[47][38] The digressions provide a powerful impression of historical depth, imitated by Tolkien in The Lord of the Rings, a work that embodies many other elements from the poem.[48]

Authorship and date[edit]

The dating of Beowulf has attracted considerable scholarly attention; opinion differs as to whether it was first written in the 8th century, whether it was nearly contemporary with its 11th-century manuscript, and whether a proto-version (possibly a version of the "Bear's Son Tale") was orally transmitted before being transcribed in its present form.[49] Albert Lord felt strongly that the manuscript represents the transcription of a performance, though likely taken at more than one sitting.[50] J. R. R. Tolkien believed that the poem retains too genuine a memory of Anglo-Saxon paganism to have been composed more than a few generations after the completion of the Christianisation of England around AD 700,[51] and Tolkien's conviction that the poem dates to the 8th century has been defended by scholars including Tom Shippey, Leonard Neidorf, Rafael J. Pascual, and Robert D. Fulk.[52][53][54] An analysis of several Old English poems by a team including Neidorf suggests that Beowulf is the work of a single author, though other scholars disagree.[55]

The claim to an early 11th-century date depends in part on scholars who argue that, rather than the transcription of a tale from the oral tradition by an earlier literate monk, Beowulf reflects an original interpretation of an earlier version of the story by the manuscript's two scribes. On the other hand, some scholars argue that linguistic, palaeographical (handwriting), metrical (poetic structure), and onomastic (naming) considerations align to support a date of composition in the first half of the 8th century;[56][57][58] in particular, the poem's apparent observation of etymological vowel-length distinctions in unstressed syllables (described by Kaluza's law) has been thought to demonstrate a date of composition prior to the earlier ninth century.[53][54] However, scholars disagree about whether the metrical phenomena described by Kaluza's law prove an early date of composition or are evidence of a longer prehistory of the Beowulf metre;[59] B.R. Hutcheson, for instance, does not believe Kaluza's law can be used to date the poem, while claiming that "the weight of all the evidence Fulk presents in his book[b] tells strongly in favour of an eighth-century date."[60]

From an analysis of creative genealogy and ethnicity, Craig R. Davis suggests a composition date in the AD 890s, when King Alfred of England had secured the submission of Guthrum, leader of a division of the Great Heathen Army of the Danes, and of Aethelred, ealdorman of Mercia. In this thesis, the trend of appropriating Gothic royal ancestry, established in Francia during Charlemagne's reign, influenced the Anglian kingdoms of Britain to attribute to themselves a Geatish descent. The composition of Beowulf was the fruit of the later adaptation of this trend in Alfred's policy of asserting authority over the Angelcynn, in which Scyldic descent was attributed to the West-Saxon royal pedigree. This date of composition largely agrees with Lapidge's positing of a West-Saxon exemplar c. 900.[61]

The location of the poem's composition is intensely disputed. In 1914, F.W. Moorman, the first professor of English Language at University of Leeds, claimed that Beowulf was composed in Yorkshire,[62] but E. Talbot Donaldson claims that it was probably composed during the first half of the eighth century, and that the writer was a native of what was then called West Mercia, located in the Western Midlands of England. However, the late tenth-century manuscript "which alone preserves the poem" originated in the kingdom of the West Saxons – as it is more commonly known.[63]

Manuscript[edit]

Beowulf survived to modern times in a single manuscript, written in ink on parchment, later damaged by fire. The manuscript measures 245 × 185 mm.[64]

Provenance[edit]

The poem is known only from a single manuscript, estimated to date from around 975–1025, in which it appears with other works.[2] The manuscript therefore dates either to the reign of Æthelred the Unready, characterised by strife with the Danish king Sweyn Forkbeard, or to the beginning of the reign of Sweyn's son Cnut the Great from 1016. The Beowulf manuscript is known as the Nowell Codex, gaining its name from 16th-century scholar Laurence Nowell. The official designation is "British Library, Cotton Vitellius A.XV" because it was one of Sir Robert Bruce Cotton's holdings in the Cotton library in the middle of the 17th century. Many private antiquarians and book collectors, such as Sir Robert Cotton, used their own library classification systems. "Cotton Vitellius A.XV" translates as: the 15th book from the left on shelf A (the top shelf) of the bookcase with the bust of Roman Emperor Vitellius standing on top of it, in Cotton's collection. Kevin Kiernan argues that Nowell most likely acquired it through William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, in 1563, when Nowell entered Cecil's household as a tutor to his ward, Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford.[65]

The earliest extant reference to the first foliation of the Nowell Codex was made sometime between 1628 and 1650 by Franciscus Junius (the younger). The ownership of the codex before Nowell remains a mystery.[66]

The Reverend Thomas Smith (1638–1710) and Humfrey Wanley (1672–1726) both catalogued the Cotton library (in which the Nowell Codex was held). Smith's catalogue appeared in 1696, and Wanley's in 1705.[67] The Beowulf manuscript itself is identified by name for the first time in an exchange of letters in 1700 between George Hickes, Wanley's assistant, and Wanley. In the letter to Wanley, Hickes responds to an apparent charge against Smith, made by Wanley, that Smith had failed to mention the Beowulf script when cataloguing Cotton MS. Vitellius A. XV. Hickes replies to Wanley "I can find nothing yet of Beowulph."[68] Kiernan theorised that Smith failed to mention the Beowulf manuscript because of his reliance on previous catalogues or because either he had no idea how to describe it or because it was temporarily out of the codex.[69]

The manuscript passed to Crown ownership in 1702, on the death of its then owner, Sir John Cotton, who had inherited it from his grandfather, Robert Cotton. It suffered damage in a fire at Ashburnham House in 1731, in which around a quarter of the manuscripts bequeathed by Cotton were destroyed.[70] Since then, parts of the manuscript have crumbled along with many of the letters. Rebinding efforts, though saving the manuscript from much degeneration, have nonetheless covered up other letters of the poem, causing further loss. Kiernan, in preparing his electronic edition of the manuscript, used fibre-optic backlighting and ultraviolet lighting to reveal letters in the manuscript lost from binding, erasure, or ink blotting.[71]

Writing[edit]

The Beowulf manuscript was transcribed from an original by two scribes, one of whom wrote the prose at the beginning of the manuscript and the first 1939 lines, before breaking off in mid-sentence. The first scribe made a point of carefully regularizing the spelling of the original document into the common West Saxon, removing any archaic or dialectical features. The second scribe, who wrote the remainder, with a difference in handwriting noticeable after line 1939, seems to have written more vigorously and with less interest. As a result, the second scribe's script retains more archaic dialectic features, which allow modern scholars to ascribe the poem a cultural context.[72] While both scribes appear to have proofread their work, there are nevertheless many errors.[73] The second scribe was ultimately the more conservative copyist as he did not modify the spelling of the text as he wrote, but copied what he saw in front of him. In the way that it is currently bound, the Beowulf manuscript is followed by the Old English poem Judith. Judith was

Dark Night V2

Dark Night version 2 theme by The Joker

Download: DarkKnightV2.p3t

(5 backgrounds)

P3T Unpacker v0.12

Copyright (c) 2007. Anoop Menon

This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit!

Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip

Instructions:

Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme.

The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract.

The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename].

For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following:

p3textractor filename.p3t [destination path]Replace filename with the name of the p3t file, and replace [destination path] with the name of the folder you want the files to be extracted to. A destination path is not required. By default it will extract to extracted.filename.

Pirates of the Caribbean

Pirates of the Caribbean theme by Amras

Download: PiratesoftheCaribbean.p3t

(14 backgrounds)

| Pirates of the Caribbean | |

|---|---|

| Created by |

|

| Original work | Pirates of the Caribbean (1967) |

| Owner | The Walt Disney Company |

| Years | 1967–present |

| Print publications | |

| Novel(s) | See Books |

| Comics | See Comic books |

| Films and television | |

| Film(s) | List

|

| Games | |

| Video game(s) | List of video games |

| Miscellaneous | |

| Theme park attraction(s) |

|

| a Crossover work where characters and settings from this franchise appear. | |

Pirates of the Caribbean is a Disney media franchise encompassing numerous theme park rides, a series of films, and spin-off novels, as well as a number of related video games and other media publications. The franchise originated with Walt Disney's theme park ride of the same name, which opened at Disneyland in 1967 and was one of the last Disneyland attractions overseen by Walt Disney. Disney based the ride on pirate legends, folklore and novels, such as those by Italian writer Emilio Salgari.

Pirates of the Caribbean became a media franchise in the 2000s with the release of The Curse of the Black Pearl in 2003; it was followed by four sequels. Produced by Jerry Bruckheimer and originally written by screenwriters Ted Elliott and Terry Rossio, the films have grossed over $4.5 billion worldwide by 2019,[1] putting the film franchise 16th in the list of all-time highest-grossing franchises and film series. The rides can be found at five Disney theme park resorts.

Rides and attractions[edit]

Pirates of the Caribbean[edit]

Pirates of the Caribbean is a dark ride at Disneyland, Walt Disney World's Magic Kingdom, Tokyo Disneyland, and Disneyland Park at Disneyland Paris. Opening on March 18, 1967, the Disneyland version of Pirates of the Caribbean was the last ride that Walt Disney himself participated in designing, debuting three months after his death.[2] The ride gave rise to the song "Yo Ho (A Pirate's Life for Me)" written by George Bruns and Xavier Atencio, and performed on the ride's recording by The Mellomen.[3]

Pirate's Lair on Tom Sawyer Island[edit]

Pirate's Lair on Tom Sawyer Island is a rebranding of Tom Sawyer Island, an artificial island surrounded by the Rivers of America at Disneyland, Magic Kingdom and Tokyo Disneyland. It contains structures and caves with references to Mark Twain characters from the novel The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, and provides interactive, climbing, and scenic opportunities. At Disneyland in 2007, Disney added references to the Pirates of the Caribbean film series.

Pirates of the Caribbean: Battle for the Sunken Treasure[edit]

Pirates of the Caribbean: Battle for the Sunken Treasure is a magnetic powered dark ride at Shanghai Disneyland. It uses a storyline based on the Pirates of the Caribbean film series. It blends digital large-screen projection technology with traditional set pieces and audio animatronics. Walt Disney Imagineering designed the ride and Industrial Light & Magic created the computer-generated visual effects.[4]

Film series[edit]

- Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003)

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest (2006)

- Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End (2007)

- Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides (2011)

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales (2017)

- Untitled Pirates of the Caribbean sixth film (TBA)[5][6]

- Untitled spin-off film (TBA)[7]

Video games[edit]

- Pirates of the Caribbean (originally entitled Sea Dogs II) was released in 2003 by Bethesda Softworks to coincide with the release of Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl. Although it had no relation to the characters, it features the film's storyline about cursed Aztec gold and undead pirates, and it was the first of several games to be based on the franchise.

- The Kingdom Hearts video game series includes Port Royal as a world in Kingdom Hearts II, adapting the story of The Curse of the Black Pearl. The world returns as The Caribbean in Kingdom Hearts III, this time adapting the story of At World's End. In both games Jack Sparrow appears as a party member of the protagonist, Sora.

- Pirates of the Caribbean Multiplayer Mobile for mobile phones.

- Pirates of the Caribbean Online a massively multiplayer online role-playing game which was released in October 2007.[8]

- Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl for Game Boy Advance (Nintendo) and a few others. This game is based on Captain Jack Sparrow's misadventures in the pursuit of saving Ria Anasagasti with his shipmate Will Turner.

- Pirates of the Caribbean: The Legend of Jack Sparrow was released for the PlayStation 2 console and for PC.

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest, was released for the Nintendo DS, PlayStation Portable, Game Boy Advance and others.

- Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End was released on May 22, 2007, and was based on the film of the same name which was released on May 25. It was the first game in the series to be released for a seventh generation console.

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Armada of the Damned, an action and role playing video game, was being developed by Propaganda Games but was cancelled in October 2010.

- Lego Pirates of the Caribbean: The Video Game, released in May 2011, covers the first four films, featuring over 70 characters and over 21 levels.

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Master of the Seas, a gaming app available on Android and iOS.[9]

- Jack Sparrow, Barbossa, and Davy Jones are playable characters in Disney Infinity and other entries in its series. A playset themed after the franchise was included with the starter pack.

- Jack Sparrow, Will Turner, Elizabeth Swann, Captain Barbossa, Davy Jones and Tia Dalma appear as playable characters in the world builder game Disney Magic Kingdoms. In the game the characters and other elements are focused on the first three films.[10][11]

- As part of a crossover collaboration with the pirate setting video game Sea of Thieves, a free expansion titled A Pirate's Life was released on June 22, 2021, featuring a new original story along with characters such as Jack Sparrow, Joshamee Gibbs, and Davy Jones.

Books[edit]

Two series of young reader books have been released as prequels to the first film:

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Jack Sparrow written under the shared pseudonym of Rob Kidd (13 books, 2006 - 2009)

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Legends of the Brethren Court written by Tui T. Sutherland writing under the pseudonym of Rob Kidd (5 books, 2008–2010)

In addition there is a novel taking place between the two series:

Novelizations

- Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003 junior novelization) by Irene Trimble

- Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2006 junior novelization)

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest: Swann Song

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest: The Chase is On

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest: The Curse of Davy Jones

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest (junior novelization, 2006) by Irene Trimble

- Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End (junior novelization, 2007) by Tui T. Sutherland

- Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End: Singapore!

- Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End: The Mystic's Journey

- Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides (junior novelization, 2011) by James Ponti

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales (novelization, 2017) by Elizabeth Rudnick

Further fictional books

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales: The Brightest Star in the North: The Adventures of Carina Smyth by Meredith Rusu (2017)

- The Pirates'

CodeGuidelines: A Booke for Those Who Desire to Keep to the Code and Live a Pirate's Life written under the pseudonym of Joshamee Gibbs (2017) - Pirates of the Caribbean: A Storm at Sea

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Escape from Davy Jones

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Ghost Ship

- Pirates of the Caribbean: The Missing Pirate

Reference books

- Bring Me That Horizon: The Making of Pirates of the Caribbean

- Disney Pirates: The Definitive Collector's Anthology

- Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End: Official Strategy Guide

- Pirates of the Caribbean: From the Magic Kingdom to the Movies

- The Captain Jack Sparrow Handbook

- Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides: The Visual Guide

- Pirates of the Caribbean: The Complete Visual Guide

- Pirates of the Caribbean: The Visual Guide

- Walt Disney's Pirates of the Caribbean: The Story of the Robust Adventure in Disneyland and Walt Disney World

German novelizations

- Fluch der Karibik (2006) by Rebecca Hohlbein and Wolfgang Hohlbein

- Pirates of the Caribbean - Fluch der Karibik 2 (2006) by Rebecca Hohlbein and Wolfgang Hohlbein

- Pirates of the Caribbean - Am Ende der Welt (2007) by Rebecca Hohlbein and Wolfgang Hohlbein

Comic books[edit]

The Pirates of the Caribbean comic series by Joe Books Ltd:

- The Guardians of Windward Cove

- Smoke on the Water

- Banshee's Boon

- Mother of Water

- Beyond Port Royal

Comic book adaptions:

- Pirates of the Caribbean: At World's End (comic)

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest (comic)

- Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales: Movie Graphic Novel

- Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (comic)

Comics have also been published in the Disney Adventures and Pirati dei Caraibi magazines.

Adaptations[edit]

Several additional works have been derived from the franchise:

- In 2000, Pirates of the Caribbean: Battle for Buccaneer Gold, opened at DisneyQuest at Florida's Walt Disney World Resort. The ride allows up to five players to board a virtual pirate ship and attempt to sink other ships with water cannons.[12]

- A Pirates of the Caribbean board game Monopoly is manufactured by USAopoly.[13]

- A Pirates of the Caribbean version of the board game The Game of Life was developed.[citation needed]

- A Pirates of the Caribbean version of the board game Battleship is produced by Hasbro under the title of Battleship Command.[citation needed]

- Pirates of the Caribbean was the name of a team participating in the 2005–2006 Volvo Ocean Race. Their boat was named the Black Pearl.[14]

- The British melodic hard rock band Ten released an album entitled Isla de Muerta, the title of which is about the legendary island of the series.[citation needed]

Characters[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Johnny Depp Movies List by Box Office Sales". JohnnyDeppMoviesList.org. Archived from the original on May 24, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ^ "Disney history: Pirates of the Caribbean opens". The Orange County Register. March 14, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2014.

- ^ Drummond, Ben (March 18, 2017). "Celebrating 50 Years of Pirates of the Caribbean with 50 Fun Facts". wdwnt.com. Retrieved April 10, 2020.

- ^ Liebenson, Donald (June 21, 2016). "From Ahoy to a Joy! How Did They Design Shanghai Disney's Pirates Attraction?". millionairecorner.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2016. Retrieved August 9, 2016.

- ^ Jain, Ayushi (October 18, 2020). "Pirates of the Caribbean 6: Release Date and All Details". Finance Rewind. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ "Entertainment News Roundup: Virtual at Emmys with pandemic; UK's Meghan did not cooperate with biography and more | Entertainment". Devdiscourse. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ "Margot Robbie, Christina Hodson Reteam for New 'Pirates of the Caribbean' Movie for Disney (Exclusive) | Hollywood Reporter". www.hollywoodreporter.com. June 26, 2020. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- ^ "Disney's Pirates of the Caribbean Online". Disney. October 31, 2007. Archived from the original on October 7, 2013. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Pirates of the Caribbean: Master of the Seas Review, iPhone and iPod Touch Application Reviews and News. 148Apps (October 31, 2011). Retrieved on December 24, 2011.

- ^ "Update 4: Pirates of the Caribbean | Trailer". YouTube. September 15, 2016.

- ^ "Update 22: Pirates of the Caribbean Part 2, Peter Pan Part 2 | Livestream". YouTube. July 5, 2018.

- ^ "Disney Quest Indoor Interactive Theme Park". Orlando Tickets, Hotels, Packages. January 20, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "Piratas do Caribe: USAopoly anuncia edição especial de tabuleiro". Geek Publicitário (in Brazilian Portuguese). April 26, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "Team News: Pirates of the Caribbean". Volvo Ocean Race. Archived from the original on June 28, 2008. Retrieved August 3, 2006.

External links[edit]

Media related to Pirates of the Caribbean at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pirates of the Caribbean at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

Halloween

Halloween theme by GunsOfLiberty

Download: Halloween.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

| Halloween | |

|---|---|

Carving a jack-o'-lantern is a common Halloween tradition. | |

| Also called |

|

| Observed by | Western Christians and many non-Christians around the world[1] |

| Type | Christian, cultural |

| Significance | First day of Allhallowtide[2][3] |

| Celebrations | Trick-or-treating, costume parties, making jack-o'-lanterns, lighting bonfires, divination, apple bobbing, visiting haunted attractions |

| Observances | Church services,[4] prayer,[5] fasting,[1] vigil[6] |

| Date | 31 October |

| Related to | Samhain, Hop-tu-Naa, Calan Gaeaf, Allantide, Day of the Dead, Reformation Day, All Saints' Day, Mischief Night (cf. vigil) |

Halloween or Hallowe'en[7][8] (less commonly known as Allhalloween,[9] All Hallows' Eve,[10] or All Saints' Eve)[11] is a celebration observed in many countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christian feast of All Hallows' Day. It is at the beginning of the observance of Allhallowtide,[12] the time in the liturgical year dedicated to remembering the dead, including saints (hallows), martyrs, and all the faithful departed.[3][13][14][15] In popular culture, the day has become a celebration of horror, being associated with the macabre and supernatural.[16]

One theory holds that many Halloween traditions were influenced by Celtic harvest festivals, particularly the Gaelic festival Samhain, which are believed to have pagan roots.[17][18][19][20] Some go further and suggest that Samhain may have been Christianized as All Hallow's Day, along with its eve, by the early Church.[21] Other academics believe Halloween began solely as a Christian holiday, being the vigil of All Hallow's Day.[22][23][24][25] Celebrated in Ireland and Scotland for centuries, Irish and Scottish immigrants took many Halloween customs to North America in the 19th century,[26][27] and then through American influence various Halloween customs spread to other countries by the late 20th and early 21st century.[16][28]

Popular Halloween activities include trick-or-treating (or the related guising and souling), attending Halloween costume parties, carving pumpkins or turnips into jack-o'-lanterns, lighting bonfires, apple bobbing, divination games, playing pranks, visiting haunted attractions, telling scary stories, and watching horror or Halloween-themed films.[29] Some people practice the Christian observances of All Hallows' Eve, including attending church services and lighting candles on the graves of the dead,[30][31][32] although it is a secular celebration for others.[33][34][35] Some Christians historically abstained from meat on All Hallows' Eve, a tradition reflected in the eating of certain vegetarian foods on this vigil day, including apples, potato pancakes, and soul cakes.[36][37][38][39]

Etymology[edit]

The word Halloween or Hallowe'en ("Saints' evening"[40]) is of Christian origin;[41][42] a term equivalent to "All Hallows Eve" is attested in Old English.[43] The word hallowe[']en comes from the Scottish form of All Hallows' Eve (the evening before All Hallows' Day):[44] even is the Scots term for "eve" or "evening",[45] and is contracted to e'en or een;[46] (All) Hallow(s) E(v)en became Hallowe'en.

History[edit]

Christian origins and historic customs[edit]

Halloween is thought to have influences from Christian beliefs and practices.[47][23] The English word 'Halloween' comes from "All Hallows' Eve", being the evening before the Christian holy days of All Hallows' Day (All Saints' Day) on 1 November and All Souls' Day on 2 November.[48] Since the time of the early Church,[49] major feasts in Christianity (such as Christmas, Easter and Pentecost) had vigils that began the night before, as did the feast of All Hallows'.[50][47] These three days are collectively called Allhallowtide and are a time when Western Christians honour all saints and pray for recently departed souls who have yet to reach Heaven. Commemorations of all saints and martyrs were held by several churches on various dates, mostly in springtime.[51] In 4th-century Roman Edessa it was held on 13 May, and on 13 May 609, Pope Boniface IV re-dedicated the Pantheon in Rome to "St Mary and all martyrs".[52] This was the date of Lemuria, an ancient Roman festival of the dead.[53]

In the 8th century, Pope Gregory III (731–741) founded an oratory in St Peter's for the relics "of the holy apostles and of all saints, martyrs and confessors".[47][54] Some sources say it was dedicated on 1 November,[55] while others say it was on Palm Sunday in April 732.[56][57] By 800, there is evidence that churches in Ireland[58] and Northumbria were holding a feast commemorating all saints on 1 November.[59] Alcuin of Northumbria, a member of Charlemagne's court, may then have introduced this 1 November date in the Frankish Empire.[60] In 835, it became the official date in the Frankish Empire.[59] Some suggest this was due to Celtic influence, while others suggest it was a Germanic idea,[59] although it is claimed that both Germanic and Celtic-speaking peoples commemorated the dead at the beginning of winter.[61] They may have seen it as the most fitting time to do so, as it is a time of 'dying' in nature.[59][61] It is also suggested the change was made on the "practical grounds that Rome in summer could not accommodate the great number of pilgrims who flocked to it", and perhaps because of public health concerns over Roman Fever, which claimed a number of lives during Rome's sultry summers.[62][47]

By the end of the 12th century, the celebration had become known as the holy days of obligation in Western Christianity and involved such traditions as ringing church bells for souls in purgatory. It was also "customary for criers dressed in black to parade the streets, ringing a bell of mournful sound and calling on all good Christians to remember the poor souls".[64] The Allhallowtide custom of baking and sharing soul cakes for all christened souls,[65] has been suggested as the origin of trick-or-treating.[66] The custom dates back at least as far as the 15th century[67] and was found in parts of England, Wales, Flanders, Bavaria and Austria.[68] Groups of poor people, often children, would go door-to-door during Allhallowtide, collecting soul cakes, in exchange for praying for the dead, especially the souls of the givers' friends and relatives. This was called "souling".[67][69][70] Soul cakes were also offered for the souls themselves to eat,[68] or the 'soulers' would act as their representatives.[71] As with the Lenten tradition of hot cross buns, soul cakes were often marked with a cross, indicating they were baked as alms.[72] Shakespeare mentions souling in his comedy The Two Gentlemen of Verona (1593).[73] While souling, Christians would carry "lanterns made of hollowed-out turnips", which could have originally represented souls of the dead;[74][75] jack-o'-lanterns were used to ward off evil spirits.[76][77] On All Saints' and All Souls' Day during the 19th century, candles were lit in homes in Ireland,[78] Flanders, Bavaria, and in Tyrol, where they were called "soul lights",[79] that served "to guide the souls back to visit their earthly homes".[80] In many of these places, candles were also lit at graves on All Souls' Day.[79] In Brittany, libations of milk were poured on the graves of kinfolk,[68] or food would be left overnight on the dinner table for the returning souls;[79] a custom also found in Tyrol and parts of Italy.[81][79]

Christian minister Prince Sorie Conteh linked the wearing of costumes to the belief in vengeful ghosts: "It was traditionally believed that the souls of the departed wandered the earth until All Saints' Day, and All Hallows' Eve provided one last chance for the dead to gain vengeance on their enemies before moving to the next world. In order to avoid being recognized by any soul that might be seeking such vengeance, people would don masks or costumes".[82] In the Middle Ages, churches in Europe that were too poor to display relics of martyred saints at Allhallowtide let parishioners dress up as saints instead.[83][84] Some Christians observe this custom at Halloween today.[85] Lesley Bannatyne believes this could have been a Christianization of an earlier pagan custom.[86] Many Christians in mainland Europe, especially in France, believed "that once a year, on Hallowe'en, the dead of the churchyards rose for one wild, hideous carnival" known as the danse macabre, which was often depicted in church decoration.[87] Christopher Allmand and Rosamond McKitterick write in The New Cambridge Medieval History that the danse macabre urged Christians "not to forget the end of all earthly things".[88] The danse macabre was sometimes enacted in European village pageants and court masques, with people "dressing up as corpses from various strata of society", and this may be the origin of Halloween costume parties.[89][90][91][74]

In Britain, these customs came under attack during the Reformation, as Protestants berated purgatory as a "popish" doctrine incompatible with the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. State-sanctioned ceremonies associated with the intercession of saints and prayer for souls in purgatory were abolished during the Elizabethan reform, though All Hallow's Day remained in the English liturgical calendar to "commemorate saints as godly human beings".[92] For some Nonconformist Protestants, the theology of All Hallows' Eve was redefined; "souls cannot be journeying from Purgatory on their way to Heaven, as Catholics frequently believe and assert. Instead, the so-called ghosts are thought to be in actuality evil spirits".[93] Other Protestants believed in an intermediate state known as Hades (Bosom of Abraham).[94] In some localities, Catholics and Protestants continued souling, candlelit processions, or ringing church bells for the dead;[48][95] the Anglican church eventually suppressed this bell-ringing.[96] Mark Donnelly, a professor of medieval archaeology, and historian Daniel Diehl write that "barns and homes were blessed to protect people and livestock from the effect of witches, who were believed to accompany the malignant spirits as they traveled the earth".[97] After 1605, Hallowtide was eclipsed in England by Guy Fawkes Night (5 November), which appropriated some of its customs.[98] In England, the ending of official ceremonies related to the intercession of saints led to the development of new, unofficial Hallowtide customs. In 18th–19th century rural Lancashire, Catholic families gathered on hills on the night of All Hallows' Eve. One held a bunch of burning straw on a pitchfork while the rest knelt around him, praying for the souls of relatives and friends until the flames went out. This was known as teen'lay.[99] There was a similar custom in Hertfordshire, and the lighting of 'tindle' fires in Derbyshire.[100] Some suggested these 'tindles' were originally lit to "guide the poor souls back to earth".[101] In Scotland and Ireland, old Allhallowtide customs that were at odds with Reformed teaching were not suppressed as they "were important to the life cycle and rites of passage of local communities" and curbing them would have been difficult.[26]

In parts of Italy until the 15th century, families left a meal out for the ghosts of relatives, before leaving for church services.[81] In 19th-century Italy, churches staged "theatrical re-enactments of scenes from the lives of the saints" on All Hallow's Day, with "participants represented by realistic wax figures".[81] In 1823, the graveyard of Holy Spirit Hospital in Rome presented a scene in which bodies of those who recently died were arrayed around a wax statue of an angel who pointed upward towards heaven.[81] In the same country, "parish priests went house-to-house, asking for small gifts of food which they shared among themselves throughout that night".[81] In Spain, they continue to bake special pastries called "bones of the holy" (Spanish: Huesos de Santo) and set them on graves.[102] At cemeteries in Spain and France, as well as in Latin America, priests lead Christian processions and services during Allhallowtide, after which people keep an all night vigil.[103] In 19th-century San Sebastián, there was a procession to the city cemetery at Allhallowtide, an event that drew beggars who "appeal[ed] to the tender recollections of one's deceased relations and friends" for sympathy.[104]

Gaelic folk influence[edit]

Today's Halloween customs are thought to have been influenced by folk customs and beliefs from the Celtic-speaking countries, some of which are believed to have pagan roots.[105] Jack Santino, a folklorist, writes that "there was throughout Ireland an uneasy truce existing between customs and beliefs associated with Christianity and those associated with religions that were Irish before Christianity arrived".[106] The origins of Halloween customs are typically linked to the Gaelic festival Samhain.[107]

Samhain is one of the quarter days in the medieval Gaelic calendar and has been celebrated on 31 October – 1 November[108] in Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man.[109][110] A kindred festival has been held by the Brittonic Celts, called Calan Gaeaf in Wales, Kalan Gwav in Cornwall and Kalan Goañv in Brittany; a name meaning "first day of winter". For the Celts, the day ended and began at sunset; thus the festival begins the evening before 1 November by modern reckoning.[111] Samhain is mentioned in some of the earliest Irish literature. The names have been used by historians to refer to Celtic Halloween customs up until the 19th century,[112] and are still the Gaelic and Welsh names for Halloween.

Samhain marked the end of the harvest season and beginning of winter or the 'darker half' of the year.[114][115] It was seen as a liminal time, when the boundary between this world and the Otherworld thinned. This meant the Aos Sí, the 'spirits' or 'fairies', could more easily come into this world and were particularly active.[116][117] Most scholars see them as "degraded versions of ancient gods [...] whose power remained active in the people's minds even after they had been officially replaced by later religious beliefs".[118] They were both respected and feared, with individuals often invoking the protection of God when approaching their dwellings.[119][120] At Samhain, the Aos Sí were appeased to ensure the people and livestock survived the winter. Offerings of food and drink, or portions of the crops, were left outside for them.[121][122][123] The souls of the dead were also said to revisit their homes seeking hospitality.[124] Places were set at the dinner table and by the fire to welcome them.[125] The belief that the souls of the dead return home on one night of the year and must be appeased seems to have ancient origins and is found in many cultures.[68] In 19th century Ireland, "candles would be lit and prayers formally offered for the souls of the dead. After this the eating, drinking, and games would begin".[126]

Throughout Ireland and Britain, especially in the Celtic-speaking regions, the household festivities included divination rituals and games intended to foretell one's future, especially regarding death and marriage.[127] Apples and nuts were often used, and customs included apple bobbing, nut roasting, scrying or mirror-gazing, pouring molten lead or egg whites into water, dream interpretation, and others.[128] Special bonfires were lit and there were rituals involving them. Their flames, smoke, and ashes were deemed to have protective and cleansing powers.[114] In some places, torches lit from the bonfire were carried sunwise around homes and fields to protect them.[112] It is suggested the fires were a kind of imitative or sympathetic magic – they mimicked the Sun and held back the decay and darkness of winter.[125][129][130] They were also used for divination and to ward off evil spirits.[76] In Scotland, these bonfires and divination games were banned by the church elders in some parishes.[131] In Wales, bonfires were also lit to "prevent the souls of the dead from falling to earth".[132] Later, these bonfires "kept away the

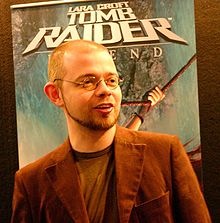

AvP-Requiem theme by GunsOfLiberty Download: AvP-Requiem.p3t P3T Unpacker v0.12 This program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit! Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip Instructions: Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme. The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract. The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following: Tom Raider theme by Telekill Download: TombRaider_2.p3t

Tomb Raider, known as Lara Croft: Tomb Raider from 2001 to 2008, is a media franchise that originated with an action-adventure video game series created by British video game developer Core Design. The franchise is currently owned by CDE Entertainment; it was formerly owned by Eidos Interactive, then by Square Enix Europe after Square Enix's acquisition of Eidos in 2009 until Embracer Group purchased the intellectual property alongside Eidos in 2022. The franchise focuses on the fictional British archaeologist Lara Croft, who travels around the world searching for lost artefacts and infiltrating dangerous tombs and ruins. Gameplay generally focuses on exploration, solving puzzles, navigating hostile environments filled with traps, and fighting enemies. Additional media has been developed for the franchise in the form of film adaptations, comics and novels.

Development of the first Tomb Raider began in 1994; it was released two years later. Its critical and commercial success prompted Core Design to develop a new game annually for the next four years, which put a strain on staff. The sixth game, Tomb Raider: The Angel of Darkness, faced difficulties during development and was considered a failure at release. This prompted Eidos to switch development duties to Crystal Dynamics, which has been the series' primary developer since. Other developers have contributed to spin-off titles and ports of mainline entries.

Tomb Raider games have sold over 95 million copies worldwide by 2022.[1] while the entire franchise generated close to $1.2 billion in revenue by 2002.[2] The series has received generally positive reviews from critics, and Lara Croft has become one of the most recognisable video game protagonists, winning accolades and earning places on the Walk of Game and Guinness World Records.

The first six Tomb Raider games were developed by Core Design, a British video game development company owned by Eidos Interactive. After the sixth game in the series was released to a mixed reception in 2003, development was transferred to American studio Crystal Dynamics, who have handled the main series since.[3] Since 2001, other developers have contributed either to ports of mainline games or with the development of spin-off titles.[3][4][5][6][7][8]

The first entry in the series Tomb Raider was released in 1996 for personal computers (PC), PlayStation and Sega Saturn consoles.[9][10] The Saturn and PlayStation versions were released in Japan in 1997.[11][12] Its sequel, Tomb Raider II, launched in 1997, again for Microsoft Windows and PlayStation. A month before release, Eidos finalised a deal with Sony Computer Entertainment to keep the console version of Tomb Raider II and future games exclusive to PlayStation until the year 2000.[9][10] The PlayStation version was released in Japan in 1998.[13] Tomb Raider III launched in 1998.[10] As with Tomb Raider II, the PlayStation version released in Japan the following year.[14] The fourth consecutive title in the series, Tomb Raider: The Last Revelation, released in 1999. In 2000, with the end of the PlayStation exclusivity deal, the game also released on the Dreamcast.[9][15] In Japan, both console versions released the following year.[16][17] Tomb Raider: Chronicles released in 2000 on the same platforms as The Last Revelation, with the PlayStation version's Japanese release as before coming the following year.[9][15][18]

After a three-year gap, Tomb Raider: The Angel of Darkness was released on Microsoft Windows and PlayStation 2 (PS2) in 2003. The PlayStation 2 version was released in Japan that same year.[15][19] The next entry, Tomb Raider: Legend, was released worldwide in 2006 for the Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 2, Xbox, Xbox 360, PlayStation Portable (PSP), GameCube, Game Boy Advance (GBA) and Nintendo DS.[8][20][21] The Xbox 360, PlayStation 2 and PlayStation Portable versions were released in Japan the same year.[22] A year later, a remake of the first game titled Tomb Raider: Anniversary was released worldwide in 2007 for Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 2, PlayStation Portable, Xbox 360 and the Wii.[23] The next entry, Tomb Raider: Underworld, was released in 2008 on Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3 (PS3), PlayStation 2, Xbox 360, Wii and DS.[24][25][26] The PlayStation 3, PlayStation 2, Xbox 360 and Wii versions were released in Japan in 2009.[27][28][29][30]

In 2011, The Tomb Raider Trilogy was released for PlayStation 3 as a compilation release that included Anniversary and Legend remastered in HD resolution, along with the PlayStation 3 version of Underworld. The disc includes avatars for PlayStation Home, a Theme Pack, new Trophies, Developer's Diary videos for the three games, and trailers for Lara Croft and the Guardian of Light as bonus content.

A reboot of the series, titled Tomb Raider, was released worldwide in 2013 for Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360.[31][32] Its sequel, Rise of the Tomb Raider, was released in 2015 on the Xbox 360 and Xbox One.[33][34] The game was part of a timed exclusivity deal with Microsoft.[35] Versions for the PlayStation 4 and Microsoft Windows were released in 2016.[36] Another sequel, Shadow of the Tomb Raider,[37] was released worldwide on PlayStation 4, Xbox One, and Microsoft Windows in 2018.[38] An arcade game based on this incarnation was released by Bandai Namco Amusement in Europe in 2018.[39]

Core Design developed two Game Boy Colour titles in the early 2000s. The first, a side-scrolling game simply titled Tomb Raider was released in 2000.[7][40] The second, its sequel, Tomb Raider: Curse of the Sword, was released in 2001.[7][41] A Game Boy Advance title called Tomb Raider: The Prophecy, was released in 2002. Unlike the first two Game Boy titles, this was developed by Ubi Soft Milan and published by Ubi Soft, adopting an isometric perspective and moving away from the side-scrolling platform-based gameplay.[7][42]

From 2010 to 2015, a subseries simply titled Lara Croft was in development at Crystal Dynamics, with different gameplay than the main series and existing in its own continuity.[43][44] The first game, Lara Croft and the Guardian of Light, was released in 2010 as a downloadable title for PC, PS3 and Xbox 360.[43] It was followed by Lara Croft and the Temple of Osiris, released for retail and download in 2014 for PC, PS4 and Xbox One.[45] Both titles were released in a compilation entitled The Lara Croft Collection for Nintendo Switch in 2023.[46] An entry for mobile devices, an endless runner platformer titled Lara Croft: Relic Run, was released in 2015.[44] Square Enix Montreal also released a platform-puzzler for mobile devices, Lara Croft Go in 2015.[47]

In 2003, four Tomb Raider titles for mobile phones were released.[48] Developed by Emerald City Games for iOS and Android devices, Tomb Raider Reloaded is an action arcade and free-to-play game released by CDE Entertainment in 2022.[49]

After the release of The Angel of Darkness in 2003, Core Design continued working on the franchise for another three years, but both of the projects under development in that period were cancelled. A sequel titled The Lost Dominion was undergoing preliminary development that year, but the negative reception of The Angel of Darkness caused it and a wider trilogy to be scrapped.[9][50] With Eidos's approval, Core Design then began development of an updated edition of the first game for the PSP called Tomb Raider: 10th Anniversary in late 2005, with a projected release date of Christmas 2006. Development continued while other Core Design staff were working on the platformer Free Running. When Core Design was sold to Rebellion Developments in June 2006,[51] Eidos requested the project's cancellation. It was suggested by staff that Eidos did not want to let outside developers handle the franchise.[52][53] An Indiana Jones "reskin" of the game was never completed, and Free Running was ultimately the studio's final title in 2007. Core Design—by then named Rebellion Derby—shut down in 2010. A January 2006 build of 10th Anniversary was leaked online in 2020, and remains available on the Internet Archive.[54][55][56]

Lara Croft is the main protagonist and playable character of the video game series. She travels around the world in search of many forgotten artefacts and locations, frequently connected to supernatural powers.[59][60][61] While her biography has changed throughout the series, her shared traits are her origins as the only daughter and heir of the aristocratic Croft family.[59][62][63] She is portrayed as intelligent, athletic, elegant, fluent in multiple languages, and determined to fulfil her own goals at any cost. She has brown eyes and brown hair worn in a braid or ponytail. The character's classic outfit consists of a turquoise singlet, light brown shorts, calf-high boots, and tall white socks. Recurring accessories include fingerless gloves, a backpack, a utility belt with holsters on either side, and twin pistols. Later games have multiple new outfits for her.[58][64][65][66]

Lara Croft has been voiced by five actresses in the video game series: Shelley Blond, Judith Gibbins, Jonell Elliott, Keeley Hawes, and Camilla Luddington. In other media, Croft was also voiced by Minnie Driver in the animated series and portrayed by Angelina Jolie and Alicia Vikander in feature films. Multiple models and body doubles have portrayed Croft in promotional material until the reboot in 2013. Eight different real-life models have portrayed her at promotional events.[67][68]

In January 2023, The Hollywood Reporter reported that Phoebe Waller-Bridge was set to write a TV show adaptation[69] of the video game franchise for Amazon. It was also reported that this would involve a tie-in video game and film in an interconnected universe, likened to the Marvel Cinematic Universe.[70]

The circumstances of her first adventures, along with the drive behind her adventures, differ depending on the continuity. In the original continuities, she is on a plane that crashes in the Himalayas: her journey back to civilization against the odds help to begin her journey towards her adult life as an adventuress and treasure hunter.[59][62] In the original continuity, after her ordeal in the Himalayas, she left behind her privileged life and made a living writing about her exploits as an adventurer, mercenary, and cat burglar. Shortly after these books she was disowned by her family.[71][72] In The Last Revelation, Lara was caught in a collapsing pyramid at the game's end, leaving her fate unknown: this was because the staff, exhausted from four years of non-stop development, wanted to move on from the character.[67] Chronicles was told through a series of flashbacks at a wake for Lara, while The Angel of Darkness was set an unspecified time after The Last Revelation, with Lara revealed to have survived. The circumstances of her survival were originally part of the game but were cut due to time constraints and the pushing of the publisher Eidos.[67][73]

In the Legend continuity, her mother Amelia was involved in the crash, and she is partially driven by the need to discover the truth behind her mother's disappearance and vindicate her father's theories about Amelia's disappearance.[74] This obsession with the truth is present in Anniversary, and ends up bringing the world to the brink of destruction during the events of Underworld.[75][76] Her father is referred to as Lord Henshingly Croft in the original games and Lord Richard Croft in the Legend continuity.[59][62] The Lara Croft subseries take place within their own separate continuity, devoting itself to adventures similar to earlier games while the main series goes in a different stylistic direction.[44]

In the 2013 reboot continuity, Lara's mother vanished at an early age, and her father became obsessed with finding the secrets of immortality, eventually resulting in an apparent suicide. Lara distanced herself from her father's memory, believing like many others that his obsession had caused him to go mad. After studying at university, Lara gets an opportunity to work on an archaeology program, in the search for the mythic kingdom of Yamatai. The voyage to find the kingdom results in a shipwreck on an island, which is later discovered to be Yamatai, but the island is also home to savage bandits, who were victims of previous wrecks. Lara's attempts to find a way off the island lead her to discover that the island itself is stopping them from leaving, which she discovered is linked to the still-living soul of the Sun Queen Himiko. Lara tries to find a way to banish the spirit of the sun queen in order to get home. The aftermath of the events of the game causes Lara to see that her father was right, and that she had needlessly distanced herself from him. She decides to finish his work, and uncover the mysteries of the world. The game's sequels portray Lara Croft in conflict with an ancient organization Trinity, in their quest to obtain supernatural items for their world domination.

The gameplay of Tomb Raider is primarily based around an action-adventure framework, with Lara navigating environments and solving mechanical and environmental puzzles, in addition to fighting enemies and avoiding traps. These puzzles, primarily set within ancient tombs and temples, can extend across multiple rooms and areas within a level. Lara can swim through water, a rarity in games at the time that has continued through the series.[20][67][77][78] According to original software engineer and later studio manager Gavin Rummery, the original set-up of interlinking rooms was inspired by Egyptian multi-roomed tombs, particularly the tomb of Tutankhamun.[67] The feel of the gameplay was intended to evoke that of the 1989 video game Prince of Persia.[79] In the original games, Lara utilised a "bulldozer" steering set-up, with two buttons pushing her forward and back and two buttons steering her left and right, and in combat Lara automatically locked onto enemies when they came within range. The camera automatically adjusts depending on Lara's action, but defaults to a third-person perspective in most instances. This basic formula remained unchanged through the first series of games. Angel of Darkness added stealth elements.[77][78][80][81]

For Legend, the control scheme and character movement was redesigned to provide a smooth and fluid experience. One of the key elements present was how buttons for different actions cleanly transitioned into different actions, along with these moves being incorporated into combat to create effects such as stunning or knocking down enemies. Quick-time events were added into certain segments within each level, and many of the puzzles were based around sophisticated in-game physics.[20][67][82][83] Anniversary, while going through the same locales of the original game, was rebuilt using the gameplay and environmental puzzles of Legend.[84] For Underworld, the gameplay was redesigned around a phrase the staff had put to themselves: "What Could Lara Do?". Using this set-up, they created a greater variety of moves and greater interaction with the environment, along with expanding and improving combat.[85]

The gameplay underwent another major change for the 2013 reboot. Gameplay altered from progression through linear levels to navigating an open world, with hunting for supplies and upgrading equipment and weapons becoming a key part of gameplay, yet tombs were mostly optional, and platforming was less present in comparison to combat. The combat was redesigned to be similar to the Uncharted series: the previous reticle-based lock-on mechanics were replaced by a free-roaming aim.[86] Rise of the Tomb Raider built on the 2013 reboot's foundation, adding dynamic weather systems, reintroducing swimming, and increasing the prevalence of non-optional tombs with more platforming elements.[87]

The concept for Tomb Raider originated in 1994 at Core Design, a British game development studio.[88] One of the people involved in its creation was Toby Gard, who was mostly responsible for creating the character of Lara Croft. Gard originally envisioned the character as a man: company co-founder Jeremy Heath-Smith was worried the character would be seen as derivative of Indiana Jones, so Gard changed the character's gender. Her design underwent mult The Wire theme by original_copycat Download: TheWire.p3t

The Wire is an American crime drama television series created and primarily written by American author and former police reporter David Simon. The series was broadcast by the cable network HBO in the United States. The Wire premiered on June 2, 2002, and ended on March 9, 2008, comprising 60 episodes over five seasons. The idea for the show started out as a police drama loosely based on the experiences of Simon's writing partner Ed Burns, a former homicide detective and public school teacher.[4]

Set and produced in Baltimore, Maryland, The Wire introduces a different institution of the city and its relationship to law enforcement in each season while retaining characters and advancing storylines from previous seasons. The five subjects are, in chronological order; the illegal drug trade, the port system, the city government and bureaucracy, education and schools, and the print news medium. Simon chose to set the show in Baltimore because of his familiarity with the city.[4]

When the series first aired, the large cast consisted mainly of actors who were unknown to television audiences, as well as numerous real-life Baltimore and Maryland figures in guest and recurring roles. Simon has said that despite its framing as a crime drama, the show is "really about the American city, and about how we live together. It's about how institutions have an effect on individuals. Whether one is a cop, a longshoreman, a drug dealer, a politician, a judge or a lawyer, all are ultimately compromised and must contend with whatever institution to which they are committed."[5]

The Wire is lauded for its literary themes, its uncommonly accurate exploration of society and politics, and its realistic portrayal of urban life. During its original run, the series received only average ratings and never won any major television awards, but it is now often cited as one of the greatest shows in the history of television.[6]

Simon has stated that he originally set out to create a police drama loosely based on the experiences of his writing partner Ed Burns, a former homicide detective and public school teacher who had worked with Simon on projects including The Corner (2000). Burns, when working on protracted investigations of violent drug dealers using surveillance technology, had often been frustrated by the bureaucracy of the Baltimore Police Department; Simon saw similarities with his own ordeals as a police reporter for The Baltimore Sun.

Simon chose to set the show in Baltimore because of his familiarity with the city. During his time as a writer and producer for the NBC program Homicide: Life on the Street, based on his book Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets (1991), also set in Baltimore, Simon had come into conflict with NBC network executives who were displeased by the show's pessimism. Simon wanted to avoid a repeat of these conflicts and chose to take The Wire to HBO, because of their working relationship from the miniseries The Corner. HBO was initially doubtful about including a police drama in its lineup but agreed to produce the pilot episode.[7][8] Simon approached the mayor of Baltimore, telling him that he wanted to give a bleak portrayal of certain aspects of the city; Simon was welcomed to work there again. He hoped the show would change the opinions of some viewers but said that it was unlikely to affect the issues it portrays.[7]

The casting of the show has been praised for avoiding big-name stars and using character actors who appear natural in their roles.[9] The looks of the cast as a whole have been described as defying TV expectations by presenting a true range of humanity on screen.[10] Many of the cast are black, consistent with the demographics of Baltimore.

Wendell Pierce, who plays Detective Bunk Moreland, was the first actor to be cast. Dominic West, who won the ostensible lead role of Detective Jimmy McNulty, sent in a tape he recorded the night before the audition's deadline of his playing out a scene by himself.[11] Lance Reddick received the role of Cedric Daniels after auditioning for the roles of Bunk and heroin addict Bubbles.[12] Michael K. Williams got the part of Omar Little after only a single audition.[13] Williams himself recommended Felicia Pearson for the role of Snoop after meeting her at a local Baltimore bar, shortly after she had served prison time for a second degree murder conviction.[14]

Several prominent real-life Baltimore figures, including former Maryland Governor Robert L. Ehrlich Jr.; Rev. Frank M. Reid III; radio personality Marc Steiner; former police chief and radio personality Ed Norris; Baltimore Sun reporter and editor David Ettlin; Howard County Executive Ken Ulman; and former mayor Kurt Schmoke have appeared in minor roles despite not being professional actors.[15][16]

"Little Melvin" Williams, a Baltimore drug lord arrested in the 1980s by an investigation that Burns had been part of, had a recurring role as a deacon beginning in the third season. Jay Landsman, a longtime police officer who inspired the character of the same name,[17] played Lieutenant Dennis Mello.[18] Baltimore police commander Gary D'Addario served as the series' technical advisor for the first two seasons[19][20] and had a recurring role as prosecutor Gary DiPasquale.[21] Simon shadowed D'Addario's shift when researching his book Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets and both D'Addario and Landsman are subjects of the book.[22]

More than a dozen cast members previously appeared on HBO's first hour-long drama Oz. J. D. Williams, Seth Gilliam, Lance Reddick, and Reg E. Cathey were featured in very prominent roles on Oz, while a number of other notable stars of The Wire, including Wood Harris, Frankie Faison, John Doman, Clarke Peters, Domenick Lombardozzi, Michael Hyatt, Michael Potts, and Method Man, appeared in at least one episode of Oz.[23] Cast members Erik Dellums, Peter Gerety, Clark Johnson, Clayton LeBouef, Toni Lewis and Callie Thorne also appeared on Homicide: Life on the Street, the earlier and award-winning network television series also based on Simon's book; Lewis appeared on Oz as well. A number of cast members, as well as crew members, also appeared in the preceding HBO miniseries The Corner including Clarke Peters, Reg E. Cathey, Lance Reddick, Corey Parker Robinson, Robert F. Chew, Delaney Williams, and Benay Berger.