Windows Vista theme by WeirdKid

Download: Vista_WeirdKid.p3t

(1 background)

| Version of the Windows NT operating system | |

Screenshot of Windows Vista Ultimate, showing its desktop, taskbar, Start menu, Windows Sidebar, Welcome Center, and glass effects of Windows Aero | |

| Developer | Microsoft |

|---|---|

| Source model | |

| Released to manufacturing | November 8, 2006[2] |

| General availability | January 30, 2007[3] |

| Final release | Service Pack 2[4] (6.0.6002.24170) / July 21, 2017[5] |

| Marketing target | Consumer and Business |

| Update method | |

| Platforms | IA-32 and x86-64 |

| Kernel type | Hybrid (NT) |

| Userland | Windows API, NTVDM, SUA |

| License | Proprietary commercial software |

| Preceded by | Windows XP (2001) |

| Succeeded by | Windows 7 (2009) |

| Official website | Windows Vista (archived at the Wayback Machine) |

| Support status | |

| Mainstream support ended on April 10, 2012[6] Extended support ended on April 11, 2017[6] | |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Windows Vista |

|---|

| New features |

| Siblings |

Windows Vista is a major release of the Windows NT operating system developed by Microsoft. It was the direct successor to Windows XP, released five years earlier, which was then the longest time span between successive releases of Microsoft Windows. It was released to manufacturing on November 8, 2006, and over the following two months, it was released in stages to business customers, original equipment manufacturers (OEMs), and retail channels. On January 30, 2007, it was released internationally and was made available for purchase and download from the Windows Marketplace; it is the first release of Windows to be made available through a digital distribution platform.[7]

Development of Windows Vista began in 2001 when it was codenamed "Longhorn"; originally envisioned as a minor successor to Windows XP, it gradually included numerous new features from the then-next major release of Windows codenamed "Blackcomb", after which it was repositioned as a major release of Windows, and it consequently underwent a protracted development that was unprecedented for Microsoft. Most new features were prominently based on a new presentation layer codenamed Avalon, a new communications architecture codenamed Indigo, and a relational storage platform codenamed WinFS — all built on the premature .NET Framework; however, this proved to be untenable due to incompleteness of technologies and ways in which new features were added, and Microsoft changed the project in 2004. Many new features were eventually reimplemented during development, but Microsoft ceased using managed code to develop the operating system.[8]

New features of Windows Vista include a graphical user interface and visual style referred to as Windows Aero; a content index and desktop search platform called Windows Search; new peer-to-peer technologies to simplify sharing files and media between computers and devices on a home network; and new multimedia tools such as Windows DVD Maker. Windows Vista included version 3.0 of the .NET Framework, allowing software developers to write applications without traditional Windows APIs. There are major architectural overhauls to audio, display, network, and print sub-systems; deployment, installation, servicing, and startup procedures are also revised. It is the first release of Windows built on Microsoft's Trustworthy Computing initiative and emphasized security with the introduction of many new security and safety features such as BitLocker and User Account Control.

The ambitiousness and scope of these changes, and the abundance of new features earned positive reviews, but Windows Vista was the subject of frequent negative press and significant criticism. Criticism of Windows Vista focused on driver, peripheral, and program incompatibility; digital rights management; excessive authorization from the new User Account Control; inordinately high system requirements when contrasted with Windows XP; its protracted development; longer boot time; and more restrictive product licensing. Windows Vista deployment and satisfaction rates were consequently lower than those of Windows XP, and it is considered a market failure;[9][10] however, its use surpassed Microsoft's pre-launch two-year-out expectations of achieving 200 million users[11] (with an estimated 330 million users by 2009).[12] On October 22, 2010, Microsoft ceased retail distribution of Windows Vista; OEM supply ceased a year later.[13] Windows Vista was succeeded by Windows 7 in 2009.

Mainstream support for Windows Vista ended on April 10, 2012 and extended support ended on April 11, 2017.[6]

Development[edit]

Microsoft began work on Windows Vista, known at the time by its codename "Longhorn", in May 2001,[14] five months before the release of Windows XP. It was originally expected to ship in October 2003 as a minor step between Windows XP and "Blackcomb", which was planned to be the company's next major operating system release. Gradually, "Longhorn" assimilated many of the important new features and technologies slated for Blackcomb, resulting in the release date being pushed back several times in three years. In some builds of Longhorn, their license agreement said "For the Microsoft product codenamed 'Whistler'". Many of Microsoft's developers were also re-tasked to build updates to Windows XP and Windows Server 2003 to strengthen security. Faced with ongoing delays and concerns about feature creep, Microsoft announced on August 27, 2004, that it had revised its plans. For this reason, Longhorn was reset to start work on componentizing the Windows Server 2003 Service Pack 1 codebase, and over time re-incorporating the features that would be intended for an actual operating system release. However, some previously announced features such as WinFS were dropped or postponed, and a new software development methodology called the Security Development Lifecycle was incorporated to address concerns with the security of the Windows codebase, which is programmed in C, C++ and assembly. Longhorn became known as Vista in 2005. Vista in Spanish means view.[15][16]

Longhorn[edit]

The early development stages of Longhorn were generally characterized by incremental improvements and updates to Windows XP. During this period, Microsoft was fairly quiet about what was being worked on, as their marketing and public relations efforts were more strongly focused on Windows XP, and Windows Server 2003, which was released in April 2003. Occasional builds of Longhorn were leaked onto popular file sharing networks such as IRC, BitTorrent, eDonkey and various newsgroups, and so most of what is known about builds before the first sanctioned development release of Longhorn in May 2003 is derived from these builds.

After several months of relatively little news or activity from Microsoft with Longhorn, Microsoft released Build 4008, which had made an appearance on the Internet around February 28, 2003.[17] It was also privately handed out to a select group of software developers. As an evolutionary release over build 3683, it contained several small improvements, including a modified blue "Plex" theme and a new, simplified Windows Image-based installer that operates in graphical mode from the outset, and completed an install of the operating system in approximately one third the time of Windows XP on the same hardware. An optional "new taskbar" was introduced that was thinner than the previous build and displayed the time differently. The most notable visual and functional difference, however, came with Windows Explorer. The incorporation of the Plex theme made blue the dominant color of the entire application. The Windows XP-style task pane was almost completely replaced with a large horizontal pane that appeared under the toolbars. A new search interface allowed for filtering of results, searching for Windows help, and natural-language queries that would be used to integrate with WinFS. The animated search characters were also removed. The "view modes" were also replaced with a single slider that would resize the icons in real-time, in the list, thumbnail, or details mode, depending on where the slider was. File metadata was also made more visible and more easily editable, with more active encouragement to fill out missing pieces of information. Also of note was the conversion of Windows Explorer to being a .NET application.

Most builds of Longhorn and Vista were identified by a label that was always displayed in the bottom-right corner of the desktop. A typical build label would look like "Longhorn Build 3683.Lab06_N.020923-1821". Higher build numbers did not automatically mean that the latest features from every development team at Microsoft was included. Typically, a team working on a certain feature or subsystem would generate their working builds which developers would test with, and when the code was deemed stable, all the changes would be incorporated back into the main development tree at once. At Microsoft, several "Build labs" exist where the compilation of the entirety of Windows can be performed by a team. The name of the lab in which any given build originated is shown as part of the build label, and the date and time of the build follow that. Some builds (such as Beta 1 and Beta 2) only display the build label in the version information dialog (Winver). The icons used in these builds are from Windows XP.

At the Windows Hardware Engineering Conference (WinHEC) in May 2003, Microsoft gave their first public demonstrations of the new Desktop Window Manager and Aero. The demonstrations were done on a revised build 4015 which was never released. Several sessions for developers and hardware engineers at the conference focused on these new features, as well as the Next-Generation Secure Computing Base (previously known as "Palladium"), which at the time was Microsoft's proposed solution for creating a secure computing environment whereby any given component of the system could be deemed "trusted". Also at this conference, Microsoft reiterated their roadmap for delivering Longhorn, pointing to an "early 2005" release date.[18]

Development reset[edit]

By 2004, it had become obvious to the Windows team at Microsoft that they were losing sight of what needed to be done to complete the next version of Windows and ship it to customers. Internally, some Microsoft employees were describing the Longhorn project as "another Cairo" or "Cairo.NET", referring to the Cairo development project that the company embarked on through the first half of the 1990s, which never resulted in a shipping operating system (though nearly all the technologies developed in that time did end up in Windows 95 and Windows NT[19]). Microsoft was shocked in 2005 by Apple's release of Mac OS X Tiger. It offered only a limited subset of features planned for Longhorn, in particular fast file searching and integrated graphics and sound processing, but appeared to have impressive reliability and performance compared to contemporary Longhorn builds.[20] Most Longhorn builds had major Windows Explorer system leaks which prevented the OS from performing well, and added more confusion to the development teams in later builds with more and more code being developed which failed to reach stability.

In a September 23, 2005 front-page article in The Wall Street Journal,[21] Microsoft co-president Jim Allchin, who had overall responsibility for the development and delivery of Windows, explained how development of Longhorn had been "crashing into the ground" due in large part to the haphazard methods by which features were introduced and integrated into the core of the operating system, without a clear focus on an end-product. Allchin went on to explain how in December 2003, he enlisted the help of two other senior executives, Brian Valentine and Amitabh Srivastava, the former being experienced with shipping software at Microsoft, most notably Windows Server 2003,[22] and the latter having spent his career at Microsoft researching and developing methods of producing high-quality testing systems.[23] Srivastava employed a team of core architects to visually map out the entirety of the Windows operating system, and to proactively work towards a development process that would enforce high levels of code quality, reduce interdependencies between components, and in general, "not make things worse with Vista".[24] Since Microsoft decided that Longhorn needed to be further componentized, work started on builds (known as the Omega-13 builds, named after a time travel device in the film Galaxy Quest[25]) that would componentize existing Windows Server 2003 source code, and over time add back functionality as development progressed. Future Longhorn builds would start from Windows Server 2003 Service Pack 1 and continue from there.

This change, announced internally to Microsoft employees on August 26, 2004, began in earnest in September, though it would take several more months before the new development process and build methodology would be used by all of the development teams. A number of complaints came from individual developers, and Bill Gates himself, that the new development process was going to be prohibitively difficult to work within.

As Windows Vista[edit]

By approximately November 2004, the company had considered several names for the final release, ranging from simple to fanciful and inventive. In the end, Microsoft chose Windows Vista as confirmed on July 22, 2005, believing it to be a "wonderful intersection of what the product really does, what Windows stands for, and what resonates with customers, and their needs". Group Project Manager Greg Sullivan told Paul Thurrott "You want the PC to adapt to you and help you cut through the clutter to focus on what's important to you. That's what Windows Vista is all about: "bringing clarity to your world" (a reference to the three marketing points of Vista—Clear, Connected, Confident), so you can focus on what matters to you".[26] Microsoft co-president Jim Allchin also loved the name, saying that "Vista creates the right imagery for the new product capabilities and inspires the imagination with all the possibilities of what can be done with Windows—making people's passions come alive."[27]

After Longhorn was named Windows Vista in July 2005, an unprecedented beta-test program was started, involving hundreds of thousands of volunteers and companies. In September of that year, Microsoft started releasing regular Community Technology Previews (CTP) to beta testers from July 2005 to February 2006. The first of these was distributed at the 2005 Microsoft Professional Developers Conference, and was subsequently released to beta testers and Microsoft Developer Network subscribers. The builds that followed incorporated most of the planned features for the final product, as well as a number of changes to the user interface, based largely on feedback from beta testers. Windows Vista was deemed feature-complete with the release of the "February CTP", released on February 22, 2006, and much of the remainder of the work between that build and the final release of the product focused on stability, performance, application and driver compatibility, and documentation. Beta 2, released in late May, was the first build to be made available to the general public through Microsoft's Customer Preview Program. It was downloaded over 5 million times. Two release candidates followed in September and October, both of which were made available to a large number of users.[28]

At the Intel Developer Forum on March 9, 2006, Microsoft announced a change in their plans to support EFI in Windows Vista. The UEFI 2.0 specification (which replaced EFI 1.10) was not completed until early 2006, and at the time of Microsoft's announcement, no firmware manufacturers had completed a production implementation which could be used for testing. As a result, the decision was made to postpone the introduction of UEFI support to Windows; support for UEFI on 64-bit platforms was postponed until Vista Service Pack 1 and Windows Server 2008 and 32-bit UEFI would not be supported, as Microsoft did not expect many such systems to be built because the market was quickly moving to 64-bit processors.[29][30]

While Microsoft had originally hoped to have the consumer versions of the operating system available worldwide in time for the 2006 holiday shopping season, it announced in March 2006 that the release date would be pushed back to January 2007 in order to give the company—and the hardware and software companies that Microsoft depends on for providing device drivers—additional time to prepare. Because a release to manufacturing (RTM) build is the final version of code shipped to retailers and other distributors, the purpose of a pre-RTM build is to eliminate any last "show-stopper" bugs that may prevent the code from responsibly being shipped to customers, as well as anything else that consumers may find troublesome. Thus, it is unlikely that any major new features would be introduced; instead, work would focus on Vista's fit and finish. In just a few days, developers had managed to drop Vista's bug count from over 2470 on September 22 to just over 1400 by the time RC2 shipped in early October. However, they still had a way to go before Vista was ready to RTM. Microsoft's internal processes required Vista's bug count to drop to 500 or fewer before the product could go into escrow for RTM.[31] For most of the pre-RTM builds, only 32-bit editions were released.

On June 14, 2006, Windows developer Philip Su posted a blog entry which decried the development process of Windows Vista, stating that "The code is way too complicated, and that the pace of coding has been tremendously slowed down by overbearing process."[32] The same post also described Windows Vista as having approximately 50 million lines of code, with about 2,000 developers working on the product. During a demonstration of the speech recognition feature new to Windows Vista at Microsoft's Financial Analyst Meeting on July 27, 2006, the software recognized the phrase "Dear mom" as "Dear aunt". After several failed attempts to correct the error, the sentence eventually became "Dear aunt, let's set so double the killer delete select all".[33] A developer with Vista's speech recognition team later explained that there was a bug with the build of Vista that was causing the microphone gain level to be set very high, resulting in the audio being received by the speech recognition software being "incredibly distorted".[34]

Windows Vista build 5824 (October 17, 2006) was supposed to be the RTM release, but a bug, where the OOBE hangs at the start of the WinSAT Assessment (if upgraded from Windows XP), requiring the user to terminate msoobe.exe by pressing Shift+F10 to open Command Prompt using either command-line tools or Task Manager prevented this, damaging development and lowering the chance that it would hit its January 2007 deadline.[35]

Development of Windows Vista came to an end when Microsoft announced that it had been finalized on November 8, 2006, and was concluded by co-president of Windows development, Jim Allchin.[36] The RTM's build number had also jumped to 6000 to reflect Vista's internal version number, NT 6.0.[37] Jumping RTM build numbers is common practice among consumer-oriented Windows versions, like Windows 98 (build 1998), Windows 98 SE (build 2222), Windows Me (build 3000) or Windows XP (build 2600), as compared to the business-oriented versions like Windows 2000 (build 2195) or Server 2003 (build 3790). On November 16, 2006, Microsoft made the final build available to MSDN and Technet Plus subscribers.[38] A business-oriented Enterprise edition was made available to volume license customers on November 30, 2006.[39] Windows Vista was launched for general customer availability on January 30, 2007.[3]

New or changed features[edit]

New features introduced by Windows Vista are very numerous, encompassing significant functionality not available in its predecessors.

End-user[edit]

- Windows Aero is the new graphical user interface, which Jim Allchin stated is an acronym for Authentic, Energetic, Reflective, and Open.[40] Microsoft intended the new interface to be cleaner and more aesthetically pleasing than those of previous Windows versions, and it features advanced visual effects such as blurred glass translucencies and dynamic glass reflections and smooth window animations.[41] Laptop users report, however, that enabling Aero reduces battery life[42][43] and reduces performance. Windows Aero requires a compositing window manager called Desktop Window Manager.

- Windows Shell offers a new range of organization, navigation, and search capabilities: Task Panes in Windows Explorer are removed, with the relevant tasks moved to a new command bar. The navigation pane can now be displayed when tasks are available, and it has been updated to include a new "Favorite Links" that houses shortcuts to common locations. An incremental search search box now appears at all times in Windows Explorer. The address bar has been replaced with a breadcrumb navigation bar, which means that multiple locations in a hierarchy can be navigated without needing to go back and forth between locations. Icons now display thumbnails depicting contents of items and can be dynamically scaled in size (up to 256 × 256 pixels). A new preview pane allows users to see thumbnails of items and play tracks, read contents of documents, and view photos when they are selected. Groups of items are now selectable and display the number of items in each group. A new details pane allows users to manage metadata. There are several new sharing features, including the ability to directly share files. The Start menu also now includes an incremental search box — allowing the user to press the ⊞ Win key and start typing to instantly find an item or launch a program — and the All Programs list uses a vertical scroll bar instead of the cascading flyout menu of Windows XP.[41]

- Windows Search is a new content index desktop search platform that replaces the Indexing Service of previous Windows versions to enable incremental searches for files and non-file items — documents, emails, folders, programs, photos, tracks, and videos — and contents or details such as attributes, extensions, and filenames across compatible applications.[41]

- Windows Sidebar is a translucent panel that hosts gadgets that display details such as feeds and sports scores on the Windows desktop; the Sidebar can be hidden and gadgets can also be placed on the desktop itself.[41]

- Internet Explorer 7 is a significant revision over Internet Explorer 6 with a new user interface comprising additional address bar features, a new search box, enhanced page zoom, RSS feed functionality, and support for tabbed browsing (with an optional "quick tabs" feature that shows thumbnails of each open tab). Anti-phishing software is introduced that combines client-side scanning with an optional online service; it checks with Microsoft the address being visited to determine its legitimacy, compares the address with a locally stored list of legitimate addresses, and uses heuristics to determine whether an address's characteristics are indicative of phishing attempts. In Windows Vista, it runs in isolation from other applications (protected mode); exploits and malicious software are restricted from writing to any location beyond Temporary Internet Files without explicit user consent.

- Windows Media Player 11 is a significant update to Microsoft's Windows Media Player for playing and organizing photos, tracks, and videos. New features include an updated GUI for the media library, disc spanning, enhanced audio fingerprinting, instant search capabilities, item organization features, synchronization features, the ability to share the media library over a network with other Windows Vista machines, Xbox 360 integration, and

Dirt

Dirt Theme by aguba

Download: Dirt.p3t

(1 background)

The great dust heap of London at Battle Bridge in 1836, next to the Smallpox Hospital

Dirty Dicks is a Bishopsgate pub named after Dirty Dick, who once owned it and was notoriously filthy.

Dirt-covered sidewalk in Brooklyn, NYC being swept during a community clean-up Dirt is any matter considered unclean, especially when in contact with a person's clothes, skin, or possessions. In such cases, they are said to become dirty. Common types of dirt include:

- Debris: scattered pieces of waste or remains

- Dust: a general powder of organic or mineral matter

- Filth: foul matter such as excrement

- Grime: a black, ingrained dust such as soot

- Soil: the mix of clay, sand, and humus which lies on top of bedrock. The term 'soil' may be used to refer to unwanted substances or dirt that are deposited onto surfaces such as clothing.[1]

Etymology[edit]

The word dirt first appears in Middle English and was probably borrowed from the Old Norse drit, meaning 'excrement'.[2]

Exhibitions and studies[edit]

A season of artworks and exhibits on the theme of dirt was sponsored by the Wellcome Trust in 2011. The centrepiece was an exhibition at the Wellcome Collection showing pictures and histories of notable dirt such as the great dust heaps at Euston and King's Cross in the 19th century and the Fresh Kills landfill which was once the world's largest landfill.[3]

Cleaning[edit]

When things are dirty, they are usually cleaned with solutions like hard surface cleaner and other chemical solutions; much domestic activity is for this purpose—washing, sweeping, and so forth.[4]

In a commercial setting, a dirty appearance gives a bad impression. An example of such a place is a restaurant. The dirt in such cases may be classified as temporary, permanent, and deliberate. Temporary dirt is streaks and detritus that may be removed by ordinary daily cleaning. Permanent dirt is ingrained stains or physical damage to an object, which requires major renovation to remove. Deliberate dirt is that which results from design decisions such as decor in dirty orange or grunge styling.[5]

Disposal[edit]

As cities developed, arrangements were made for the disposal of trash through the use of waste management services. In the United Kingdom, the Public Health Act 1875 required households to place their refuse into a container that could be moved so that it could be carted away. This was the first legal creation of the dustbin.[6]

Health[edit]

Modern society is now thought to be more hygienic. Lack of contact with microorganisms in dirt when growing up is hypothesised to be the cause of the epidemic of allergies such as asthma.[7] The human immune system requires activation and exercise in order to function properly and exposure to dirt may achieve this.[8] For example, the presence of staphylococcus bacteria on the surface of the skin regulates the inflammation which results from injury.[9]

Even when no visible dirt is present, contamination by microorganisms, especially pathogens, can still cause an object or location to be considered dirty. For example, computer keyboards are especially dirty as they contain on average 70 times more microbes than a lavatory seat.[10]

People and animals may eat dirt. This is thought to be caused by mineral deficiency[citation needed] and so the condition is commonly seen in pregnant women.[11]

Neurosis[edit]

People may become obsessed by dirt and engage in fantasies and compulsive behaviour about it, such as making and consuming mud pies and pastries.[12] The source of such thinking may be genetic, as the emotion of disgust is common and the location for this activity in the brain has been proposed.[13]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Arno Cahn, ed. (2003). 5th World Conference on Detergents. p. 154. ISBN 9781893997400 – via Google Books.

- ^ "dirt, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OED/1353882326. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Brian Dillon (23 March 2011), "Dirt: the Filthy Reality of Everyday Life, Welcome Collection", The Daily Telegraph, archived from the original on 24 March 2011

- ^ Mindy Lewis (2009), Dirt: The Quirks, Habits, and Passions of Keeping House, ISBN 9781580052610

- ^ John B. Hutchings (2003), Expectations and the Food Industry, ISBN 9780306477096

- ^ V.K. Prabhakar (2000), Encyclopaedia of Environmental Pollution and Awareness in the 21st Century, p. 10, ISBN 9788126106516

- ^ Dirt can be good for children, say scientists, BBC, 23 November 2009

- ^ Mary Ruebush (2009), Why Dirt Is Good: 5 Ways to Make Germs Your Friends, ISBN 9781427798046

- ^ Lai, Y; Di Nardo, A; Nakatsuji, T; Leichtle, A; Yang, Y; Cogen, AL; Wu, ZR; Hooper, LV; Schmidt, RR (22 November 2009), "Commensal bacteria regulate Toll-like receptor 3–dependent inflammation after skin injury", Nature Medicine, 15 (12): 1377–82, doi:10.1038/nm.2062, PMC 2880863, PMID 19966777

- ^ The joy of dirt, The Economist, 17 December 2009

- ^ López, LB; Ortega Soler, CR; de Portela, ML (March 2004). "Pica during pregnancy: a frequently underestimated problem". Archivos Latinoamericanos de Nutricion. 54 (1): 17–24. PMID 15332352.

- ^ Lawrence S. Kubie, "The Fantasy of Dirt", The Psychoanalytical Quarterly, 6: 388–425

- ^ Valerie Curtis, Adam Biran (2001), "Dirt, Disgust, and Disease: Is Hygiene in Our Genes?", Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 44 (1): 17–31, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.324.760, doi:10.1353/pbm.2001.0001, PMID 11253302, S2CID 15675303

Further reading[edit]

- Terence McLaughlin (1971), Dirt: a social history as seen through the uses and abuses of dirt, Stein and Day, ISBN 9780812814125

- Suellen Hoy (1996), Chasing Dirt: The American Pursuit of Cleanliness, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780195111286

- Pamela Janet Wood (2005), Dirt: filth and decay in a new world arcadia, Auckland University Press, ISBN 9781869403485

- Ben Campkin, Rosie Cox (2007), Dirt: new geographies of cleanliness and contamination, I.B. Tauris, ISBN 9781845116729

- Virginia Smith; et al. (2011), Dirt: The Filthy Reality of Everyday Life, Profile Books Limited, ISBN 9781846684791

External links[edit]

Media related to Dirtiness at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dirtiness at Wikimedia Commons- Dirt season at the Wellcome Collection

ST (See Through) Silver

ST Silver theme by chasgta

Download: STSilver.p3t

(1 background)

P3T Unpacker v0.12

Copyright (c) 2007. Anoop MenonThis program unpacks Playstation 3 Theme files (.p3t) so that you can touch-up an existing theme to your likings or use a certain wallpaper from it (as many themes have multiple). But remember, if you use content from another theme and release it, be sure to give credit!

Download for Windows: p3textractor.zip

Instructions:

Download p3textractor.zip from above. Extract the files to a folder with a program such as WinZip or WinRAR. Now there are multiple ways to extract the theme.

The first way is to simply open the p3t file with p3textractor.exe. If you don’t know how to do this, right click the p3t file and select Open With. Alternatively, open the p3t file and it will ask you to select a program to open with. Click Browse and find p3textractor.exe from where you previously extracted it to. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename]. After that, all you need to do for any future p3t files is open them and it will extract.

The second way is very simple. Just drag the p3t file to p3textractor.exe. It will open CMD and extract the theme to extracted.[filename].

For the third way, first put the p3t file you want to extract into the same folder as p3textractor.exe. Open CMD and browse to the folder with p3extractor.exe. Enter the following:

p3textractor filename.p3t [destination path]Replace filename with the name of the p3t file, and replace [destination path] with the name of the folder you want the files to be extracted to. A destination path is not required. By default it will extract to extracted.filename.Final Fantasy

Final Fantasy theme by Shadowfyre

Download: FinalFantasy.p3t

(3 backgrounds)

Final Fantasy[a] is a fantasy anthology media franchise created by Hironobu Sakaguchi which is owned, developed, and published by Square Enix (formerly Square). The franchise centers on a series of fantasy role-playing video games. The first game in the series was released in 1987, with 16 numbered main entries having been released to date.

The franchise has since branched into other video game genres such as tactical role-playing, action role-playing, massively multiplayer online role-playing, racing, third-person shooter, fighting, and rhythm, as well as branching into other media, including films, anime, manga, and novels.

Final Fantasy is mostly an anthology series with primary installments being stand-alone role-playing games, each with different settings, plots and main characters, but the franchise is linked by several recurring elements, including game mechanics and recurring character names. Each plot centers on a particular group of heroes who are battling a great evil, but also explores the characters' internal struggles and relationships. Character names are frequently derived from the history, languages, pop culture, and mythologies of cultures worldwide. The mechanics of each game involve similar battle systems and maps.

Final Fantasy has been both critically and commercially successful. Several entries are regarded as some of the greatest video games, with the series selling more than 185 million copies worldwide, making it one of the best-selling video game franchises of all time. The series is well known for its innovation, visuals, such as the inclusion of full-motion videos, photorealistic character models, and music by Nobuo Uematsu. It has popularized many features now common in role-playing games, also popularizing the genre as a whole in markets outside Japan.

Media[edit]

Games[edit]

The first installment of the series was released in Japan on December 18, 1987. Subsequent games are numbered and given a story unrelated to previous games, so the numbers refer to volumes rather than to sequels. Many Final Fantasy games have been localized for markets in North America, Europe, and Australia on numerous video game consoles, personal computers (PC), and mobile phones. As of June 2023, the series includes the main installments from Final Fantasy to Final Fantasy XVI, as well as direct sequels and spin-offs, both released and confirmed as being in development. Most of the older games have been remade or re-released on multiple platforms.[1]

Main series[edit]

Release timeline 1987 Final Fantasy 1988 Final Fantasy II 1989 1990 Final Fantasy III 1991 Final Fantasy IV 1992 Final Fantasy V 1993 1994 Final Fantasy VI 1995 1996 1997 Final Fantasy VII 1998 1999 Final Fantasy VIII 2000 Final Fantasy IX 2001 Final Fantasy X 2002 Final Fantasy XI 2003 2004 2005 2006 Final Fantasy XII 2007 2008 2009 Final Fantasy XIII 2010 Final Fantasy XIV (original) 2011 2012 2013 Final Fantasy XIV 2014 2015 2016 Final Fantasy XV 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 Final Fantasy XVI Three Final Fantasy installments were released on the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). Final Fantasy was released in Japan in 1987 and in North America in 1990.[2][3] It introduced many concepts to the console RPG genre, and has since been remade on several platforms.[3] Final Fantasy II, released in 1988 in Japan, has been bundled with Final Fantasy in several re-releases.[3][4][5] The last of the NES installments, Final Fantasy III, was released in Japan in 1990,[6] but was not released elsewhere until a Nintendo DS remake came out in 2006.[5]

The Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) also featured three installments of the main series, all of which have been re-released on several platforms. Final Fantasy IV was released in 1991; in North America, it was released as Final Fantasy II.[7][8] It introduced the "Active Time Battle" system.[9] Final Fantasy V, released in 1992 in Japan, was the first game in the series to spawn a sequel: a short anime series, Final Fantasy: Legend of the Crystals.[3][10][11] Final Fantasy VI was released in Japan in 1994, titled Final Fantasy III in North America.[12]

The PlayStation console saw the release of three main Final Fantasy games. Final Fantasy VII (1997) moved away from the two-dimensional (2D) graphics used in the first six games to three-dimensional (3D) computer graphics; the game features polygonal characters on pre-rendered backgrounds. It also introduced a more modern setting, a style that was carried over to the next game.[3] It was also the second in the series to be released in Europe, with the first being Final Fantasy Mystic Quest. Final Fantasy VIII was published in 1999, and was the first to consistently use realistically proportioned characters and feature a vocal piece as its theme music.[3][13] Final Fantasy IX, released in 2000, returned to the series' roots, by revisiting a more traditional Final Fantasy setting, rather than the more modern worlds of VII and VIII.[3][14]

Three main installments, as well as one online game, were published for the PlayStation 2.[15][16][17] Final Fantasy X (2001) introduced full 3D areas and voice acting to the series, and was the first to spawn a sub-sequel (Final Fantasy X-2, published in 2003).[18][19] The first massively multiplayer online role-playing game (MMORPG) in the series, Final Fantasy XI, was released on the PS2 and PC in 2002, and later on the Xbox 360.[20][21] It introduced real-time battles instead of random encounters.[21] Final Fantasy XII, published in 2006, also includes real-time battles in large, interconnected playfields.[22][23] The game is also the first in the main series to utilize a world used in a previous game, namely the land of Ivalice, which was previously featured in Final Fantasy Tactics and Vagrant Story.[24]

In 2009, Final Fantasy XIII was released in Japan, and in North America and Europe the following year, for PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360.[25][26] It is the flagship installment of the Fabula Nova Crystallis Final Fantasy series[27] and became the first mainline game to spawn two sub-sequels (XIII-2 and Lightning Returns).[28] It was also the first game released in Chinese and high definition along with being released on two consoles at once. Final Fantasy XIV, a MMORPG, was released worldwide on Microsoft Windows in 2010, but it received heavy criticism when it was launched, prompting Square Enix to rerelease the game as Final Fantasy XIV: A Realm Reborn, this time to the PlayStation 3 as well, in 2013.[29] Final Fantasy XV is an action role-playing game that was released for PlayStation 4 and Xbox One in 2016.[30][31] Originally a XIII spin-off titled Versus XIII, XV uses the mythos of the Fabula Nova Crystallis series, although in many other respects the game stands on its own and has since been distanced from the series by its developers.[38] The sixteenth mainline entry, Final Fantasy XVI,[39] was released in 2023 for PlayStation 5.[40]

Remakes, sequels and spin-offs[edit]

Final Fantasy has spawned numerous spin-offs and metaseries. Several are, in fact, not Final Fantasy games, but were rebranded for North American release. Examples include the SaGa series, rebranded The Final Fantasy Legend, and its two sequels, Final Fantasy Legend II and III.[41] Final Fantasy Mystic Quest was specifically developed for a United States audience, and Final Fantasy Tactics is a tactical RPG that features many references and themes found in the series.[42][43] The spin-off Chocobo series, Crystal Chronicles series, and Kingdom Hearts series also include multiple Final Fantasy elements.[41][44] In 2003, the Final Fantasy series' first sub-sequel, Final Fantasy X-2, was released.[45] Final Fantasy XIII was originally intended to stand on its own, but the team wanted to explore the world, characters and mythos more, resulting in the development and release of two sequels in 2011 and 2013 respectively, creating the series' first official trilogy.[28] Dissidia Final Fantasy was released in 2009, a fighting game that features heroes and villains from the first ten games of the main series.[46] It was followed by a prequel in 2011,[47] a sequel in 2015[48] and a mobile spin-off in 2017.[49][50] Other spin-offs have taken the form of subseries—Compilation of Final Fantasy VII, Ivalice Alliance, and Fabula Nova Crystallis Final Fantasy. In 2022, Square Enix released an action-role playing title Stranger of Paradise: Final Fantasy Origin developed in collaboration with Team Ninja, which takes place in an alternate, reimagined reality based on the setting of the original Final Fantasy game, depicting a prequel story that explores the origins of the antagonist Chaos and the emergence of the four Warriors of Light.[51][52] Enhanced 3D remakes of Final Fantasy III and IV were released in 2006 and 2007 respectively.[53][54] The first installment of the Final Fantasy VII Remake project was released on the PlayStation 4 in 2020.[55] The second and latest installment of the remake trilogy, Final Fantasy VII Rebirth, was released on the PlayStation 5 in 2024.[56]

Other media[edit]

Film and television[edit]

Final Fantasy in film and television 1994 Final Fantasy: Legend of the Crystals 1995–2000 2001 Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within Final Fantasy: Unlimited 2002–2004 2005 Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children Last Order: Final Fantasy VII 2006–2015 2016 Kingsglaive: Final Fantasy XV Brotherhood: Final Fantasy XV 2017 Final Fantasy XIV: Dad of Light 2018 2019 Final Fantasy XV: Episode Ardyn – Prologue Square Enix has expanded the Final Fantasy series into various media. Multiple anime and computer-generated imagery (CGI) films have been produced that are based either on individual Final Fantasy games or on the series as a whole. The first was an original video animation (OVA), Final Fantasy: Legend of the Crystals, a sequel to Final Fantasy V. The story was set in the same world as the game, although 200 years in the future. It was released as four 30-minute episodes, first in Japan in 1994 and later in the United States by Urban Vision in 1998. In 2001, Square Pictures released its first feature film, Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within. The film is set on a future Earth invaded by alien life forms.[57] The Spirits Within was the first animated feature to seriously attempt to portray photorealistic CGI humans, but was considered a box office bomb and garnered mixed reviews.[57][58][59]

A 25-episode anime television series, Final Fantasy: Unlimited, was released in 2001 based on the common elements of the Final Fantasy series. It was broadcast in Japan by TV Tokyo and released in North America by ADV Films.

In 2005, Final Fantasy VII: Advent Children, a feature length direct-to-DVD CGI film, and Last Order: Final Fantasy VII, a non-canon OVA,[60] were released as part of the Compilation of Final Fantasy VII. Advent Children was animated by Visual Works, which helped the company create CG sequences for the games.[61] The film, unlike The Spirits Within, became a commercial success.[62][63][64][65] Last Order, on the other hand, was released in Japan in a special DVD bundle package with Advent Children. Last Order sold out quickly[66] and was positively received by Western critics,[67][68] though fan reaction was mixed over changes to established story scenes.[69]

Two animated tie-ins for Final Fantasy XV were released as part of a larger multimedia project dubbed the Final Fantasy XV Universe. Brotherhood is a series of five 10-to-20-minute-long episodes developed by A-1 Pictures and Square Enix detailing the backstories of the main cast. Kingsglaive, a CGI film released prior to the game in Summer 2016, is set during the game's opening and follows new and secondary characters.[70][71][72][73] In 2019, Square Enix released a short anime, produced by Satelight Inc, called Final Fantasy XV: Episode Ardyn – Prologue on their YouTube channel which acts as the background story for the final piece of DLC for Final Fantasy XV giving insight into Ardyn's past.

Square Enix also released Final Fantasy XIV: Dad of Light in 2017, an 8-episode Japanese soap opera based, featuring a mix of live-action scenes and Final Fantasy XIV gameplay footage.

As of June 2019, Sony Pictures Television is working on a live-action adaptation of the series with Hivemind and Square Enix. Jason F. Brown, Sean Daniel and Dinesh Shamdasani for Hivemind are the producers while Ben Lustig and Jake Thornton were attached as writers and executive producers for the series.[74]

Other media[edit]

Several video games have either been adapted into or have had spin-offs in the form of manga and novels. The first was the novelization of Final Fantasy II in 1989, and was followed by a manga adaptation of Final Fantasy III in 1992.[75][76] The past decade has seen an increase in the number of non-video game adaptations and spin-offs. Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within has been adapted into a novel, the spin-off game Final Fantasy Crystal Chronicles has been adapted into a manga, and Final Fantasy XI had a novel and manga set in its continuity.[77][78][79][80] Seven novellas based on the Final Fantasy VII universe have also been released. The Final Fantasy: Unlimited story was partially continued in novels and a manga after the anime series ended.[81] The Final Fantasy X and XIII series have also had novellas and audio dramas released. Final Fantasy Tactics Advance has been adapted into a radio drama, and Final Fantasy: Unlimited has received a radio drama sequel.

A trading card game named Final Fantasy Trading Card Game is produced by Square Enix and Hobby Japan, first released Japan in 2012 with an English version in 2016.[82] The game has been compared to Magic: the Gathering, and a tournament circuit for the game also takes place.[83][84]

Common elements[edit]

Although most Final Fantasy installments are independent, many gameplay elements recur throughout the series.[85][86] Most games conta

Twist

Twist theme by Precisi

Download: Twist.p3t

(4 backgrounds)

Twist may refer to:

In arts and entertainment[edit]

Film, television, and stage[edit]

- Twist (2003 film), a 2003 independent film loosely based on Charles Dickens's novel Oliver Twist

- Twist (2021 film), a 2021 modern rendition of Oliver Twist starring Rafferty Law

- The Twist (1976 film), a 1976 film co-written and directed by Claude Chabrol

- The Twist (1992 film), a 1992 documentary film directed by Ron Mann

- Twist (stage play), a 1995 stage thriller by Miles Tredinnick

- Twist, the main character on television series The Fresh Beat Band and its spin-off Fresh Beat Band of Spies

- Oliver Twist (disambiguation), name of several film, television, and musical adaptations based on Charles Dickens's novel Oliver Twist

- "Twist" (Only Murders in the Building), a 2021 episode of the TV series Only Murders in the Building

- Jack Twist, a character in the 2005 film Brokeback Mountain

- Twist Morgan, a character in the television series Spaced

Music[edit]

- Twist (album), a 1994 album by New Zealand singer-songwriter Dave Dobbyn

- The Twist (album), a 1984 album by Danish indiepop band Gangway

- "The Twist" (song), a song by Hank Ballard, covered by Chubby Checker, a hit in 1960

- "The Twist", a song from the album Grow Up and Blow Away by Metric

- "The Twist", a song from the album Coming Back Hard Again by hip hop band The Fat Boys

- "Twist" (Phish song), from the 2000 album Farmhouse by Phish

- "Twist" (Goldfrapp song), a single from the 2003 album Black Cherry by Goldfrapp

- Twist, an album by Chris & Cosey

- "Twist", a song from the album Unfinished Business by Nathan Sykes

- "Twist" a song from the album A Hundred Days Off by Underworld

- "Twist", the opener of the 1996 Korn album, Life Is Peachy

- "Twisting", a song from the album Flood by They Might Be Giants

- Twist (band), a rock band from Birmingham, England, UK

Other media[edit]

- Twist ending, an unexpected conclusion or climax to a work of fiction

- Twist (magazine), an American teen magazine

- Twist (Cano novel), a novel by Harkaitz Cano

- Twist (Östergren novel), a novel by Klas Östergren

- Twist (TV network), an American television network

- Oliver Twist, a novel by Charles Dickens, and its main character

Finance[edit]

- Transaction Workflow Innovation Standards Team (TWIST), a non-profit financial industry standards group

- Operation Twist, an effort (in 1961, and again in 2011) by the U.S. Federal Reserve to lower long-term interest rates

Mathematics, science, and technology[edit]

- Twist (mechanics), the torsion of an object

- Twist (mathematics), a geometric quantity associated with a ribbon

- Twists of curves, a method of deriving related curves

- Twist (screw theory), in applied mathematics and physics

- Twist (software), a test automation solution by ThoughtWorks Studios

- Ellipse Twist, a French hang glider

- Twist fungus (Dilophospora alopecuri)

- Twisting properties, in statistics

- Twist transcription factor, a gene protein

People[edit]

- Barry McGee (born 1966), also known as Twist, painter and graffiti artist

- Leroy "Twist" Casey (born 1973), disk jockey

- Liz Twist (born 1956), British Member of Parliament

- Susan Twist, British actress

- Tony Twist (born 1968), Canadian hockey player

Places[edit]

- Twist, Arkansas, a city in the United States

- Twist, Germany, a municipality in Lower Saxony

Sport[edit]

- Aerial twist, an acrobatic maneuver in gymnastics

- Twist lifts, a type of lift in pairs figure skating

Other uses[edit]

- Twist (cocktail garnish), a decorative piece of citrus zest

- Twist (confectionery), a Norwegian bag of sweets, now produced in Sweden

- Twist (dance), a rock and roll dance

- Twist (poker), a special round in some variants of stud poker

- Twist (ride), a popular amusement ride, often seen on travelling funfairs

- French twist (hairstyle), a hair styling technique

- Twist tobacco, a type of chewing tobacco

- Sail twist, a phenomenon in sailing

- Wing twist, a design choice in aeronautics

See also[edit]

Portal

Portal theme by Mr.Chubigans

Download: Portal.p3t

(1 background)

Look up portal in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

Look up portal in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.Portal often refers to:

- Portal (architecture), an opening in a wall of a building, gate or fortification, or the extremities (ends) of a tunnel

Portal may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment[edit]

Gaming[edit]

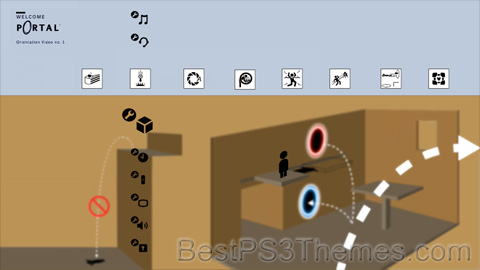

- Portal (series), a series of video games developed by Valve

- Portal (video game), a 2007 video game, the first in the series

- Portal 2, the 2011 sequel

- Portal Stories: Mel, a mod for Portal 2

- Portal Revolution, a mod for Portal 2

- Portal Reloaded, a mod for Portal 2

- Aperture Tag, a mod for Portal 2

- Portal (1986 video game), a 1986 computer game by Activision

- Portal (Magic: The Gathering), a set in the Magic: The Gathering card game

- Portal (video game element), an element in video game design

Music[edit]

- Portal (band), an Australian extreme metal band

- Portal (album), a 1994 album by Wendy & Carl

- "Portal", a 2014 song by Lights Little Machines

- Portals (Arsonists Get All the Girls album), 2009

- Portals (Sub Focus and Wilkinson album), 2020

- "Portals", by Alan Silvestri, from the soundtrack for the film Avengers: Endgame

- Portals (EP), a 2022 EP by Kirk Hammett

- Portals (Melanie Martinez album), 2023

Other uses in arts and entertainment[edit]

- Portal (comics), a Marvel Comics character

- Portal (magic trick), an illusion performed by David Copperfield

- Portal (TV series), a series about MMORPGs

- Portal (sculptures), interactive art sculptures videoconferencing two cities

- Vilnius–Lublin Portal, a 2021 interactive public art installation

- New York–Dublin Portal, a 2024 interactive public art installation

- Portals (initiative), a public art initiative that connects people in different world cities through real-time videoconferencing

- The Portal (podcast), a podcast hosted by Eric Weinstein

Computing[edit]

Gateways to information[edit]

- Captive portal, controlling connections to the Internet

- Enterprise portal, a framework to provide a single point of access to a variety of information and tools

- Intranet portal, a gateway that unifies access to all enterprise information and applications

- Web portal, a site that functions as a point of access to information on the World Wide Web

Other uses in computing[edit]

- Meta Portal, a screen-enhanced smart speaker

- Portal rendering, an optimization technique in 3D computer graphics

- Portals network programming API, a high-performance networking programming interface for massively parallel supercomputers

- Portal Software, a company based in Cupertino, California

Places[edit]

- Portal, Arizona

- Portal, Georgia

- Portal, Nebraska

- Portal, North Dakota

- North Portal, a village in Saskatchewan adjacent to Portal, North Dakota

- Portal Peak, a mountain in Canada

- Portal, Tarporley, a country house near Tarporley, Cheshire, England

- Portal Bridge, over the Hackensack River in New Jersey

- Portal Heights, former name for a railway station in Montreal, Canada

Organisations[edit]

- Clube Atlético Portal, a football club based in Uberlândia, Brazil

- Portals Athletic F.C., a defunct football club, based in Overton, England

- Portals (paper makers), a UK paper making company

Other uses[edit]

- NCAA transfer portal, a database and compliance tool facilitating US college athletes who wish to change schools

- Portal frame, a construction method

- Portal stones, a type of stone monument

- Portal (surname), shared by several notable people

- Portal venous system, an occurrence where one capillary bed drains into another through veins

- Hepatic portal system, the portal system between the digestive system and the liver

- Hepatic portal vein, a vein that drains blood from the digestive system

- Hypophyseal portal system

- Hepatic portal system, the portal system between the digestive system and the liver

See also[edit]

- Conduit (channeling)

- The Portal (disambiguation)

- Porthole, a window in the hull of a ship

- Wormhole

Tux n Tosh

The Simpsons

The Simpsons theme by HITMAN_DK

Download: TheSimpsons.p3t

(1 background)

The Simpsons

Genre Created by Matt Groening Based on The Simpsons shorts

by Matt GroeningDeveloped by - James L. Brooks

- Matt Groening

- Sam Simon

Showrunners - James L. Brooks (seasons 1–2)

- Matt Groening (seasons 1–2)

- Sam Simon (seasons 1–2)

- Al Jean (seasons 3–4; 13—32)

- Mike Reiss (seasons 3–4)

- David Mirkin (seasons 5–6)

- Bill Oakley (seasons 7–8)

- Josh Weinstein (seasons 7–8)

- Mike Scully (seasons 9–12)

- Matt Selman (season 33–present)

Voices of Theme music composer Danny Elfman Opening theme "The Simpsons Theme" Ending theme "The Simpsons Theme" (reprise) Composers Richard Gibbs (1989–1990)

Alf Clausen (1990–2017)

Bleeding Fingers Music (2017–present)Country of origin United States Original language English No. of seasons 35 No. of episodes 768 (list of episodes) Production Executive producers List- James L. Brooks

- Matt Groening

- Al Jean (1992–1993; 1995–present)

- Matt Selman (2005–present)

- John Frink (2009–present)

- Sam Simon (1989–1993)

- Mike Reiss (1992–1993; 1995–1998)

- David Mirkin (1993–1995)

- Bill Oakley (1995–1997)

- Josh Weinstein (1995–1997)

- Mike Scully (1997–2001)

- David X. Cohen (1998–1999)

- George Meyer (1999–2001)

- Carolyn Omine (2005–2006)

- Tim Long (2005–2009)

- Ian Maxtone-Graham (2005–2012)

Producers - Bonita Pietila

- Richard Raynis

- Richard Sakai

- Denise Sirkot

Editors - Don Barrozo

- Michael Bridge

Running time 21–24 minutes Production companies - Gracie Films

- 20th Television[a] (seasons 1–32)

- 20th Television Animation (season 33–present)[b]

Original release Network Fox Release December 17, 1989 –

presentThe Simpsons is an American animated sitcom created by Matt Groening for the Fox Broadcasting Company.[1][2][3] Developed by Groening, James L. Brooks, and Sam Simon, the series is a satirical depiction of American life, epitomized by the Simpson family, which consists of Homer, Marge, Bart, Lisa, and Maggie. Set in the fictional town of Springfield, it caricatures society, Western culture, television, and the human condition.

The family was conceived by Groening shortly before a solicitation for a series of animated shorts with producer Brooks. He created a dysfunctional family and named the characters after his own family members, substituting Bart for his own name; he thought Simpson was a funny name in that it sounded similar to "simpleton".[4] The shorts became a part of The Tracey Ullman Show on April 19, 1987. After three seasons, the sketch was developed into a half-hour prime time show and became Fox's first series to land in the Top 30 ratings in a season (1989–1990).

Since its debut on December 17, 1989, 768 episodes of the show have been broadcast. It is the longest-running American animated series, longest-running American sitcom, and the longest-running American scripted primetime television series, both in seasons and individual episodes. A feature-length film, The Simpsons Movie, was released in theaters worldwide on July 27, 2007, to critical and commercial success, with a sequel in development as of 2018. The series has also spawned numerous comic book series, video games, books, and other related media, as well as a billion-dollar merchandising industry. The Simpsons is a joint production by Gracie Films and 20th Television.[5]

On January 26, 2023, the series was renewed for its 35th and 36th seasons, taking the show through the 2024–25 television season.[6] Both seasons contain a combined total of 51 episodes. Seven of these episodes are season 34 holdovers, while the other 44 will be produced in the production cycle of the upcoming seasons, bringing the show's overall episode total up to 801.[7] Season 35 premiered on October 1, 2023.[8]

The Simpsons received widespread acclaim throughout its early seasons in the 1990s, which are generally considered its "golden age". Since then, it has been criticized for a perceived decline in quality. Time named it the 20th century's best television series,[9] and Erik Adams of The A.V. Club named it "television's crowning achievement regardless of format".[10] On January 14, 2000, the Simpson family was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. It has won dozens of awards since it debuted as a series, including 37 Primetime Emmy Awards, 34 Annie Awards, and 2 Peabody Awards. Homer's exclamatory catchphrase of "D'oh!" has been adopted into the English language, while The Simpsons has influenced many other later adult-oriented animated sitcom television series.

Premise[edit]

Characters[edit]

The main characters are the Simpson family, who live in the fictional "Middle America" town of Springfield.[11] Homer, the father, works as a safety inspector at the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant, a position at odds with his careless, buffoonish personality. He is married to Marge (née Bouvier), a stereotypical American housewife and mother. They have three children: Bart, a ten-year-old troublemaker and prankster; Lisa, a precocious eight-year-old activist; and Maggie, the baby of the family who rarely speaks, but communicates by sucking on a pacifier. Although the family is dysfunctional, many episodes examine their relationships and bonds with each other and they are often shown to care about one another.[12]

The family also owns a greyhound, Santa's Little Helper, (who first appeared in the episode "Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire" and a cat, Snowball II, who is replaced by a cat also called Snowball II in the fifteenth-season episode "I, (Annoyed Grunt)-Bot".[13] Extended members of the Simpson and Bouvier family in the main cast include Homer's father Abe and Marge's sisters Patty and Selma. Marge's mother Jacqueline and Homer's mother Mona appear less frequently.

The Simpsons sports a vast array of secondary and tertiary characters. The show includes a vast array of quirky supporting characters, which include Homer's friends Barney Gumble, Lenny Leonard and Carl Carlson; the school principal Seymour Skinner and staff members such as Edna Krabappel and Groundskeeper Willie; students such as Milhouse Van Houten, Nelson Muntz and Ralph Wiggum; shopkeepers such as Apu Nahasapeemapetilon, Comic Book Guy and Moe Szyslak; government figures Mayor "Diamond" Joe Quimby and Clancy Wiggum; next-door neighbor Ned Flanders; local celebrities such as Krusty the Clown and news reporter Kent Brockman; nuclear tycoon Montgomery Burns and his devoted assistant Waylon Smithers; and dozens more.

The creators originally intended many of these characters as one-time jokes or for fulfilling needed functions in the town. A number of them have gained expanded roles and subsequently starred in their own episodes. According to Matt Groening, the show adopted the concept of a large supporting cast from the comedy show SCTV.[14]

Continuity and the floating timeline[edit]

Despite the depiction of yearly milestones such as holidays or birthdays passing, the characters never age. The series uses a floating timeline in which episodes generally take place in the year the episode is produced. Flashbacks and flashforwards do occasionally depict the characters at other points in their lives, with the timeline of these depictions also generally floating relative to the year the episode is produced. For example, the 1991 episodes "The Way We Was" and "I Married Marge" depict Homer and Marge as high schoolers in the 1970s who had Bart (who is always 10 years old) in the early '80s, while the 2008 episode "That '90s Show" depicts Homer and Marge as a childless couple in the '90s, and the 2021 episode "Do Pizza Bots Dream of Electric Guitars" portrays Homer as an adolescent in the same period. The 1995 episode "Lisa's Wedding" takes place during Lisa's college years in the then-future year of 2010, the same year the show began airing its 22nd season, in which Lisa was still 8. Regarding the contradictory flashbacks, Selman stated that "they all kind of happened in their imaginary world."[15]

The show follows a loose and inconsistent continuity. For example, Krusty the Clown may be able to read in one episode, but not in another. However, it is consistently portrayed that he is Jewish, that his father was a rabbi, and that his career began in the 1960s. The latter point introduces another snag in the floating timeline: historical periods that are a core part of a character's backstory remain so even when their age makes it unlikely or impossible, such as Grampa Simpson and Principal Skinner's respective service in World War II and Vietnam.

The only episodes not part of the series' main canon are the Treehouse of Horror episodes, which often feature the deaths of main characters. Characters who die in "regular" episodes, such as Maude Flanders, Mona Simpson and Edna Krabappel, however, stay dead. Most episodes end with the status quo being restored, though occasionally major changes will stick, such as Lisa's conversions to vegetarianism and Buddhism, the divorce of Milhouse van Houten's parents, and the marriage and subsequent parenthood of Apu and Manjula.

Setting[edit]

The Simpsons takes place in a fictional American town called Springfield. Although there are many real settlements in America named Springfield,[16] the town the show is set in is fictional. The state it is in is not established. In fact, the show is intentionally evasive with regard to Springfield's location.[17] Springfield's geography and that of its surroundings is inconsistent: from one episode to another, it may have coastlines, deserts, vast farmland, mountains, or whatever the story or joke requires.[18] Groening has said that Springfield has much in common with Portland, Oregon, the city where he grew up.[19] Groening has said that he named it after Springfield, Oregon, and the fictitious Springfield which was the setting of the series Father Knows Best. He "figured out that Springfield was one of the most common names for a city in the U.S. In anticipation of the success of the show, I thought, 'This will be cool; everyone will think it's their Springfield.' And they do."[20] Many landmarks, including street names, have connections to Portland.[21]

Production[edit]

Development[edit]

James L. Brooks (pictured) asked Matt Groening to create a series of animated shorts for The Tracey Ullman Show. When producer James L. Brooks was working on the television variety show The Tracey Ullman Show, he decided to include small animated sketches before and after the commercial breaks. Having seen one of cartoonist Matt Groening's Life in Hell comic strips, Brooks asked Groening to pitch an idea for a series of animated shorts. Groening initially intended to present an animated version of his Life in Hell series.[22] However, Groening later realized that animating Life in Hell would require the rescinding of publication rights for his life's work. He therefore chose another approach while waiting in the lobby of Brooks's office for the pitch meeting, hurriedly formulating his version of a dysfunctional family that became the Simpsons.[22][23] He named the characters after his own family members, substituting "Bart" for his own name, adopting an anagram of the word brat.[22]

The Simpson family first appeared as shorts in The Tracey Ullman Show on April 19, 1987.[24] Groening submitted only basic sketches to the animators and assumed that the figures would be cleaned up in production. However, the animators merely re-traced his drawings, which led to the crude appearance of the characters in the initial shorts.[22] The animation was produced domestically at Klasky Csupo,[25][26] with Wes Archer, David Silverman, and Bill Kopp being animators for the first season.[27] The colorist, "Georgie" Gyorgyi Kovacs Peluce (Kovács Györgyike)[28][29][30][31][32][33] made the characters yellow; as Bart, Lisa and Maggie have no hairlines, she felt they would look strange if they were flesh-colored. Groening supported the decision, saying: "Marge is yellow with blue hair? That's hilarious — let's do it!"[27]

In 1989, a team of production companies adapted The Simpsons into a half-hour series for the Fox Broadcasting Company. The team included the Klasky Csupo animation house. Brooks negotiated a provision in the contract with the Fox network that prevented Fox from interfering with the show's content.[34] Groening said his goal in creating the show was to offer the audience an alternative to what he called "the mainstream trash" that they were watching.[35] The half-hour series premiered on December 17, 1989, with "Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire".[36] "Some Enchanted Evening" was the first full-length episode produced, but it did not broadcast until May 1990, as the last episode of the first season, because of animation problems.[37] In 1992, Tracey Ullman filed a lawsuit against Fox, claiming that her show was the source of the series' success. The suit said she should receive a share of the profits of The Simpsons[38]—a claim rejected by the courts.[39]

Executive producers and showrunners[edit]

Matt Groening, the creator of The Simpsons List of showrunners throughout the series' run:

- Season 1–2: Matt Groening, James L. Brooks, & Sam Simon

- Season 3–4: Al Jean & Mike Reiss

- Season 5–6: David Mirkin

- Season 7–8: Bill Oakley & Josh Weinstein

- Season 9–12: Mike Scully

- Season 13–31: Al Jean

- Season 32–present: Al Jean & Matt Selman

Matt Groening and James L. Brooks have served as executive producers during the show's entire history, and also function as creative consultants. Sam Simon, described by former Simpsons director Brad Bird as "the unsung hero" of the show,[40] served as creative supervisor for the first four seasons. He was constantly at odds with Groening, Brooks and the show's production company Gracie Films and left in 1993.[41] Before leaving, he negotiated a deal that sees him receive a share of the profits every year, and an executive producer credit despite not having worked on the show since 1993,[41][42] at least until his passing in 2015.[43] A more involved position on the show is the showrunner, who acts as head writer and manages the show's production for an entire season.[27]

Writing[edit]

The first team of writers, assembled by Sam Simon, consisted of John Swartzwelder, Jon Vitti, George Meyer, Jeff Martin, Al Jean, Mike Reiss, Jay Kogen and Wallace Wolodarsky.[44] Newer Simpsons' writing teams typically consist of sixteen writers who propose episode ideas at the beginning of each December.[45] The main writer of each episode writes the first draft. Group rewriting sessions develop final scripts by adding or removing jokes, inserting scenes, and calling for re-readings of lines by the show's vocal performers.[46] Until 2004,[47] George Meyer, who had developed the show since the first season, was active in these sessions. According to long-time writer Jon Vitti, Meyer usually invented the best lines in a given episode, even though other writers may receive script credits.[46] Each episode takes six months to produce so the show rarely comments on current events.[48]

Part of the writing staff of The Simpsons in 1992. Back row, left to right: Mike Mendel, Colin A. B. V. Lewis (partial), Jeff Goldstein, Al Jean (partial), Conan O'Brien, Bill Oakley, Josh Weinstein, Mike Reiss, Ken Tsumura, George Meyer, John Swartzwelder, Jon Vitti (partial), CJ Gibson, and David M. Stern. Front row, left to right: Dee Capelli, Lona Williams, and unknown. Credited with sixty episodes, John Swartzwelder is the most prolific writer on The Simpsons.[49] One of the best-known former writers is Conan O'Brien, who contributed to several episodes in the early 1990s before replacing David Letterman as host of the talk show Late Night.[50] English comedian Ricky Gervais wrote the episode "Homer Simpson, This Is Your Wife", becoming the first celebrity both to write and guest star in the same episode.[51] Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg, writers of the film Superbad, wrote the episode "Homer the Whopper", with Rogen voicing a character in it.[52]

At the end of 2007, the writers of The Simpsons went on strike together with the other members of the Writers Guild of America, East. The show's writers had joined the guild in 1998.[53]

In May 2023, the writers of The Simpsons went on strike together with the other members of the Writers Guild of America, East.[54][55]

Voice actors[edit]